Another magnificent clubhouse by Benno Janssen; it is now Alumni Hall of the University of Pittsburgh.

One of the many Italian Renaissance palaces in the monumental district of Oakland, this one—unlike many of the others—still serves its original purpose. It was designed by Ingham & Boyd and opened in 1938. Because of the street layout, the building is a large trapezoid with a courtyard garden. It is worth the time to pause and examine the details.

An Art Deco interpretation of traditional Doric bank architecture, with the added interest of an unusual shape: the lot forces the structure into a triangle. This substantial building from 1931 was abandoned for a while; then it was briefly the Iglesia de Cristo León de Judá, before that congregation took over an old church a few blocks away; then it was abandoned again. Now it is a store with the delightfully appropriate name “Candy Safe Market.” The exterior is a feast of artistic details.

The name comes from St. Clair Township, which originally included much of Allegheny County south of the Monongahela. Today the building is in the Knoxville neighborhood of Pittsburgh, right on the border with Mount Oliver borough.

This pair of griffins over the entrance ought to be guarding a clock, and perhaps they were at some point; but the bronze decoration where the clock should be is fairly old, if it is not original. The banner with the name of the store is hanging over this sculpture, which is why we have to look at it from this angle: old Pa Pitt thought it would be discourteous to take down the banner just to get a better picture.

One of the points of the triangle.

A Daniel Burnham design built for the McCreery & Company department store, this building opened in 1904. It originally had a classical base with a pair of arched entrances on Wood Street, but beginning in 1939 it had various alterations, so that nothing remains of the original Burnham design below the fourth floor. This was one of Burnham’s more minimalistic designs; in it we see how thin the wall can be between classicism and modernism.

Below, an abstract composition with elements of this building reflected in Two PNC Plaza across the street.

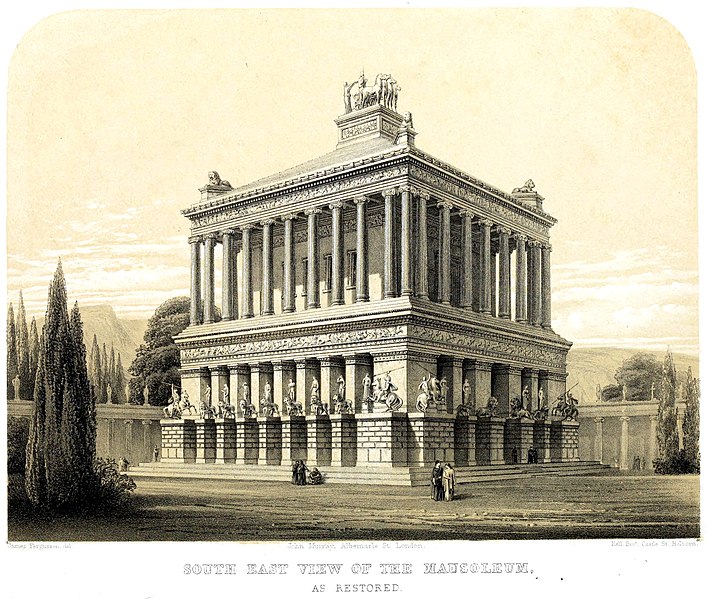

No one knows exactly what the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus looked like when it was intact. It was one of the Seven Wonders of the World, but today all that is left is a bit of rubble. The rough outlines are generally known, however, and the speculative reconstructions of it have been productive of more monumental architecture in Pittsburgh than perhaps any other classical building. At least half a dozen buildings in Pittsburgh were inspired by it: Soldiers & Sailors Hall, the Hall of Architecture at the Carnegie, Presbyterian Hospital, Allegheny General Hospital, the Gulf Building, and the Wilkins mausoleum in the Homewood Cemetery. Above is James Fergusson’s version of how it must have looked, and Fergusson’s was one of the most influential reconstructions. See if you can spot the resemblance with the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial by Henry Hornbostel: