Designed by our remarkable early modernist Frederick Scheibler, “Meado’cots” is an unusual set of terrace houses built in 1914—another Scheibler answer to the question of how to make cheap rows of houses architecturally attractive. It sat abandoned and boarded up for quite a while, but now it is inhabited and stable. The metal roofs on the central section and the cheap standard doors are not to old Pa Pitt’s taste, but they were within the budget of the new owner, and they keep the buildings standing and in good shape, with the potential for restoration with original materials later.

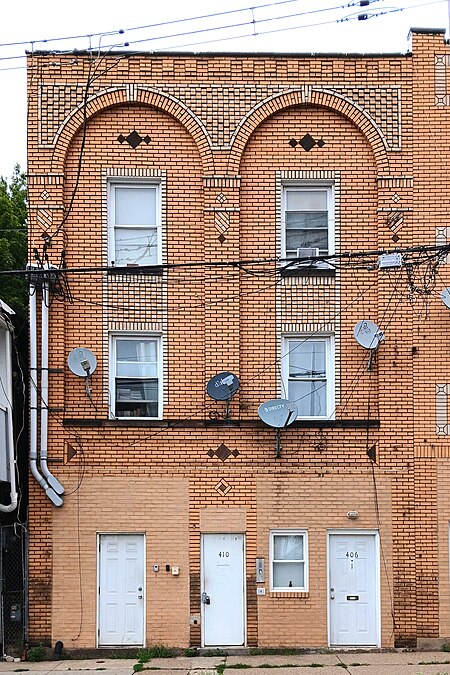

This composite of the central section from above parked-car level is made possible by a kind neighbor from across the street. He saw us struggling to hold the camera up at arm’s length and called down from a third-floor window to offer the use of his stairs for a better angle. Thank you, Homewood neighbor, for confirming Father Pitt’s impression that Homewood is a place where the neighborly virtues are strong.

Note the corner windows. They would become a badge of modernism in the 1940s, but here they are in 1912!