Le Corbusier introduced the world to the idea of the cruciform apartment building. He regarded the form as so perfect, in fact, that he proposed demolishing Paris and replacing it with a sea of cross-shaped towers.

In Pittsburgh, cruciform buildings were a bit of a fad in the late 1940s and early 1950s, probably encouraged by the national attention lavished on Gateway Center. They do have certain advantages. A cross-shaped building can give every apartment cross-ventilation and a view of open spaces, while still putting quite a bit of building on a small lot.

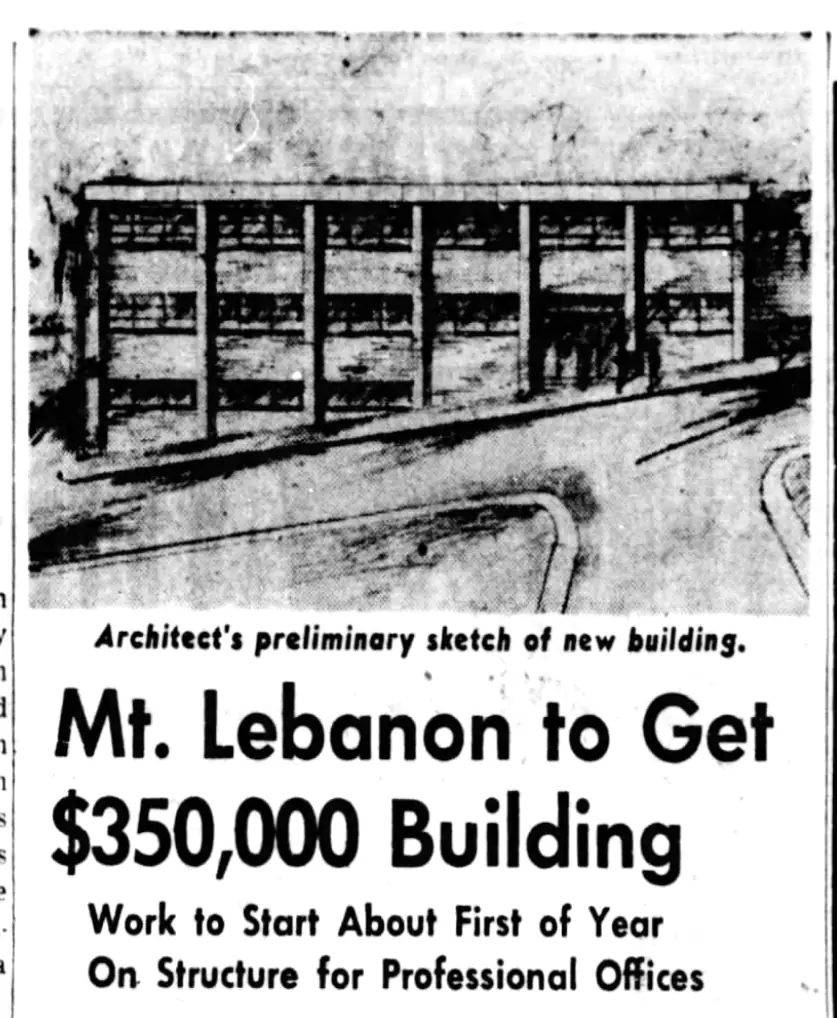

Tennyson and Van Wart were among the architects who picked up on the idea. Alfred Tennyson was a Mount Lebanon architect who would continue with a very prosperous career in the second half of the twentieth century. John Van Wart, as half of the partnership of Van Wart & Wein, had been responsible for some big projects in New York in the 1920s and early 1930s; in the middle 1930s, he moved to Pittsburgh to work for Westinghouse, and then formed a promising partnership with Tennyson. His unexpected death in 1950, probably while this building was under construction, put an end to the partnership, and Tennyson went on alone.

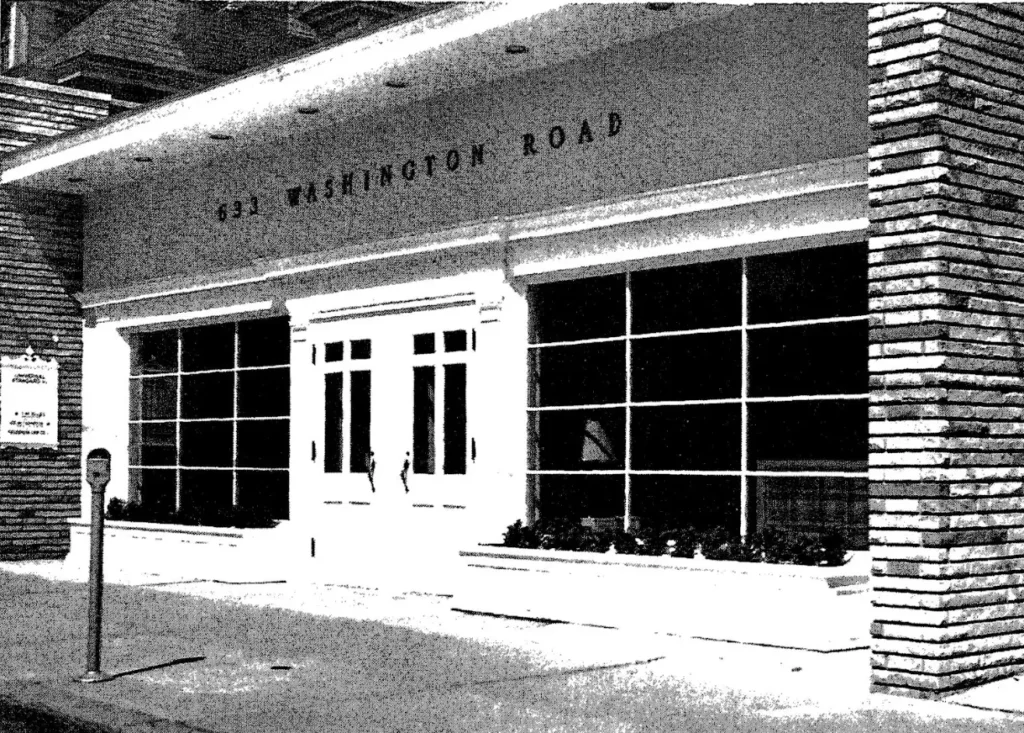

The style is typical postwar modernism, but not pure modernism. A few little decorative details, like the subtle quoins, give the modernism a slight Georgian flavor.

The scalloped woodwork, if it is not a later addition, must have been one of those details added to persuade prospective tenants that this building was, after all, respectably Colonial enough not to embarrass them.

As with many Pittsburgh buildings, the question of how many floors this one has is a complicated one. The answer varies between three and six, depending on how you look at it.