Pembroke Place is a street of unusually fine houses in the very rich part of Shadyside. We have already seen the Acheson House; here is a generous album of other houses on the street.

Pembroke Place is a street of unusually fine houses in the very rich part of Shadyside. We have already seen the Acheson House; here is a generous album of other houses on the street.

An elegant Tudor or Jacobean mansion designed by MacClure & Spahr and built in 1903, as the dormer tells us. This Post-Gazette story (reprinted in a Greenville, North Carolina, paper that does not keep it behind a paywall) tells us that a 1925 addition was designed by Benno Janssen, who had worked in the MacClure & Spahr office and may have had some responsibility for the original design. The article also tells us how vandals masquerading as interior designers rampaged through the house and painted all the interior woodwork white or pale grey to “banish dark wood,” but at least the exterior is in good shape.

The part of Dutchtown south of East Ohio Street is a tiny but densely packed treasury of Victorian styles. Old Pa Pitt took a walk on Avery Street the other evening, when the sun had moved far enough around in the sky to paint the houses on the southeast side of the street.

Is this the most beautiful breezeway in Pittsburgh? It’s certainly in the running.

In 1913, George Best decided to develop a little square of land in Oakmont by subdividing it into tiny lots and putting up modest but attractive houses. To manage the modest-but-attractive part of the scheme, he hired architect George Schwan. In American architectural history he is perhaps most famous as the architect of most of the buildings in the original section of the Goodyear Heights neighborhood of Akron, beginning in 1917. This earlier development is on a more modest scale, but it also involved putting up a bunch of houses at once with enough variation to make the neighborhood attractive.

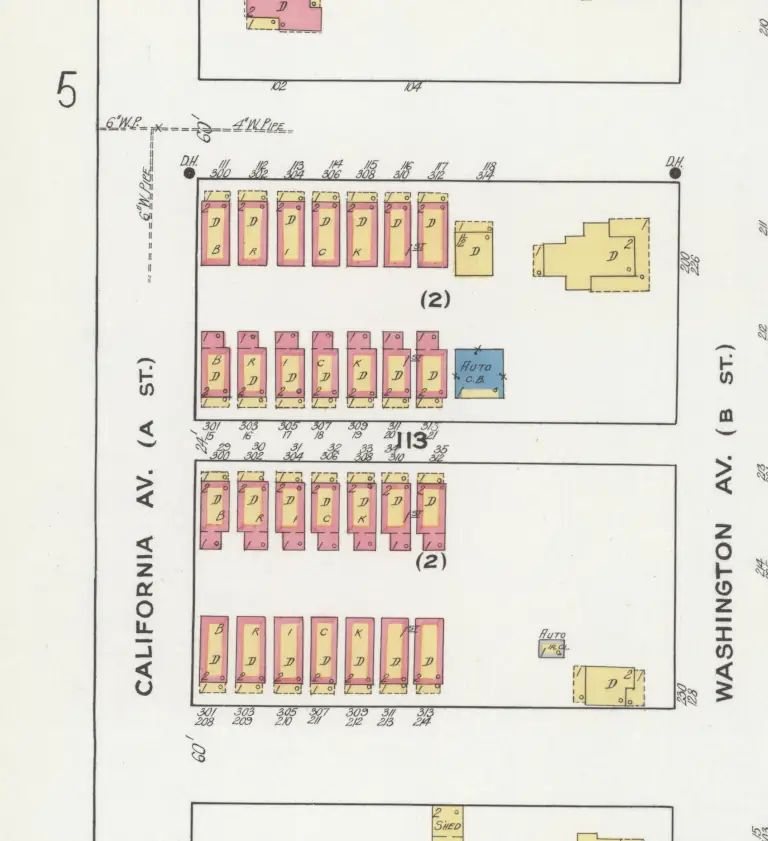

The plan had twenty-eight of these houses in four rows of seven. This Sanborn Fire Insurance map from 1921 shows the layout:

Seven houses on one side of Second street, seven on one side of Third, and fourteen somewhat smaller houses on both sides of the narrow alley Beech Street.

Originally the houses were brick on the first floors and shingle above, and they would have been charming in their modest way. Over the years the shingles have been replaced with aluminum and vinyl siding, but enough of the original character remains to show what Schwan had in mind.

These are not great works of the imagination. They are, however, a good solution to the problem posed to the architect. How do you cram as many detached houses as possible into a little square of land and still make them seem attractive? The answer is to vary a few basic designs, and thus create a streetscape with a rhythm that is not strictly repetitive, while at the same time creating a neighborhood that obviously goes together.

The real test is time. For more than a century, every single one of these houses has stood and been loved by its residents. Not one has gone missing. By the most reasonable standard, George Schwan’s project was a success, and Mr. Best certainly got his money’s worth from the architect’s commission.

We’ve seen some of the houses in Seminole Hills already, but we need no excuse to look at a few more. Like the other similar plans in Mount Lebanon, this one delights us with its wide variety of excellent designs.

A demonstration of the variety of scales found in Mission Hills. Above, a grand mansion with a whole village of outbuildings; below, just around the corner, a modest but richly stony Cape Cod.

This typical Colonial, probably from the 1930s, has a typical little round window above the front door. But what do you do if you don’t want a window there anymore?

Cameras: Sony Alpha 3000 with 7Artisans 35mm f/1.4 lens, except for the picture of the clock, which was taken with the Nikon COOLPIX P100.

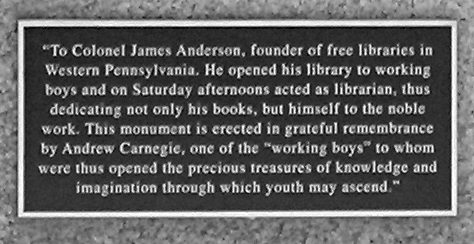

Few of the great Greek Revival mansions that surrounded Pittsburgh before the Civil War have survived. This one has, and that alone would make it important. But this one also has a place of high honor in the intellectual history of the United States. This was the home of Colonel James Anderson, the book-lover, who opened his personal library to working boys on Saturday afternoons. One of those boys was Andrew Carnegie, who attributed his later success to the education he got from reading Col. Anderson’s books. When Carnegie established his first public library in Allegheny, he donated a memorial to Col. Anderson to stand outside and remind the city that Carnegie was only following his benefactor’s example. A plaque, set up by somebody who did not understand how quotation marks work, duplicates the original inscription:

The original house was built in about 1830; additions were made in 1905—a fortunate time, since classical style had come back in fashion, and the additions were in sympathy with the original.

The house has belonged to various institutions over the years, but many of the details remain intact.

The colonnaded porch-and-balcony has Doric columns below, Ionic above—a scrupulously correct treatment. Doric was regarded as weightier than Ionic, so the lighter-looking columns are supported by the heavier-looking ones. If there were a third level, the columns would be Corinthian, the lightest of the three Greek orders.

The Dormont Park Land Company was incorporated in 1927 and almost immediately began offering lots in a little square of land laid out as the Dormont Park plan, right next to Dormont Park, the one big open space in the borough of Dormont. It was an attempt to give the middle classes what the upper classes got from Mission Hills, Virginia Manor, and similar plans in Mount Lebanon: a classy neighborhood of attractive houses of high architectural merit.

“Fully restricted, high-class and exclusive”—but within an easy stroll of the streetcar line (as it still is today).

The neighborhood largely delivered on its promise. A few lots remained unbuilt till after the Second World War, and the houses on them are not up to the high standard of the rest. But the majority are designs of merit, obviously designed by some of our best domestic architects. They are more modest than the ones in the big Mount Lebanon plans, but all the same styles are represented, just on a smaller scale.

Many of the houses retain their charming original details, like these deliberately irregular roof slates.

Old Pa Pitt has undertaken to document every house in the plan, and he is already more than two-thirds of the way to the goal. We’ll be seeing some more of Dormont Park, but meanwhile, Father Pitt has established a category for the Dormont Park plan at Wikimedia Commons, where you can see dozens more pictures.

Cameras: Sony Alpha 3000, Nikon COOLPIX P100.

As Father Pitt has remarked more than once, the variety and quality of designs in the Mount Lebanon plans like Mission Hills are constantly delightful. Here is a short stroll down Parkway Drive in Mission Hills.

This one, unusually for the neighborhood, has had paste-on shutters applied to add sophistication to the home. Our friend Dr. Boli wrote an essay about those that generated some interesting responses from his correspondents.

Here is one that has real shutters, with hinges and everything.

Old Pa Pitt is always pleased when an architect understands that a house is a three-dimensional object, not just a façade with a box behind it, and gives it rewardingly different appearances from different angles.

And, finally, here is a bit of good news for the neighborhood and the metropolis:

This new house is replacing a house that vanished a few years ago (for reasons unknown to Father Pitt, who does not always keep up with the news, and perhaps a neighbor can inform us). It has reached the stage where we can judge the design, and it is a good one. Individually it may never be Father Pitt’s favorite house, but as a citizen of the neighborhood it gets everything right. It is of similar height and size to its neighbors, and it honors the historic styles around it—look at those three-over-one Craftsman-style windows—while still being distinctly its own 21st-century self, just as all the other houses in Mission Hills are distinct and original. This is a demonstration of how new buildings can be added to historic neighborhoods.

Cameras: Nikon COOLPIX P100; Sony Alpha 3000 with a 7Artisans 35mm f/1.4 lens.

A year ago we published this picture of a row of houses in Manchester, with the second from the left under sentence of condemnation after a fire. At the time we were not sure whether it would be worth enough to restore. But it has been restored, and the whole row is looking neat and attractive again:

You would hardly know anything had happened except for a bit of soot on the bricks, which is hardly news in Pittsburgh, and the fact that the trim has been painted black.

Built in about 1865, this grand house on North Lincoln Avenue is decorated in the highest Victorian manner, and the current owners have put much thought into the color scheme for painting the elaborate wood trim.

Though it is hidden in the shadows between houses most of the day, this oriel is nevertheless festooned with decorative woodwork, including these ornate brackets: