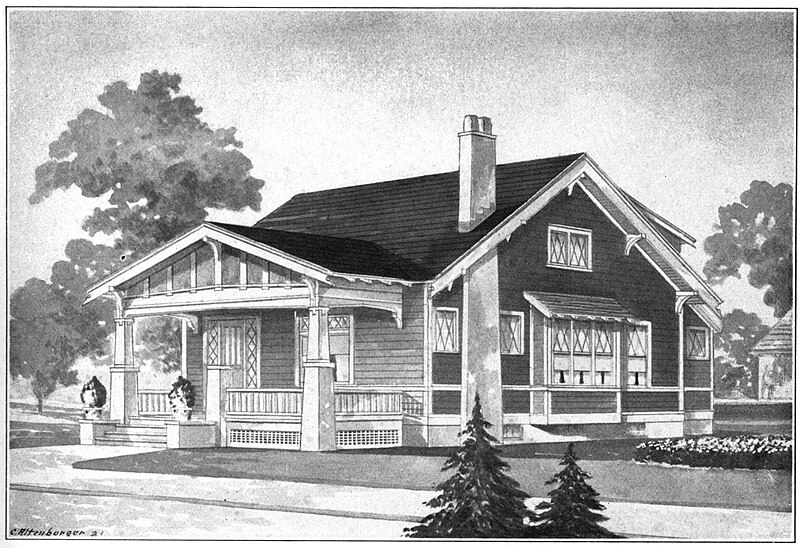

Here is a bungalow from the book Pennsylvania Homes, published in 1925 by the Retail Lumber Dealers’ Association of Pennsylvania, which had its headquarters in the Park Building in Pittsburgh.

Some graduate student right now is probably writing a thesis on “The Idea of the Bungalow in Early-Twentieth-Century American Thought.” Certainly there is enough material for a hefty academic treatise. We could probably write a thick book just on the cultural implications of 1920s song titles: “Our Bungalow of Dreams,” “We’ll Build a Bungalow,” “A Little Bungalow,” “A Cozy Little Bungalow” (that’s a different song), “There’s a Bungalow in Dixieland,” “You’re Just the Type for a Bungalow.” And so on.

A “bungalow” in American usage was a house where the rooms were all on the ground level, though often with extra bedrooms in a finished attic. It was the predecessor of the ubiquitous ranch houses of the 1960s. It was associated with the “Craftsman” style promoted by Gustav Stickley and others. Low-pitched roofs, overhanging eaves, and simple arts-and-crafts ornament were typical of the style.

What caused American houses to go from predominantly vertical to predominantly horizontal? We will not attempt to answer that question definitively; we have to leave our hypothetical graduate student some material for a thesis. We only offer some suggestions.

First, there are practical advantages to a one-level design. Advertisements often dwell on the number of steps the bungalow saves the busy housewife, which reminds us that middle-class families were beginning to consider the possibility of getting along without servants.

Second, a small bungalow could be built very cheap. It is true that a rowhouse could be built even cheaper, but the bungalow offered the privacy of a detached house. Some of these bungalows were extraordinarily tiny: that book of Pennsylvania Homes featured a “one-room” bungalow, with a tiny kitchen, dressing room, and bathroom, and one “great room” that could become a pair of bedrooms at night by drawing a folding partition across the middle. Most were not quite so tiny: a typical bungalow had a living room, dining room, kitchen, bathroom, and one or two bedrooms on the ground floor.

Third, there was the suburban ideal. In the early twentieth century, Americans were persuading themselves that what they wanted was the country life, but with city conveniences—in other words, the suburb. The city did not always have room to spread out horizontally, but the suburbs were more encouraging to horizontality.

Fourth, the bungalow—as we see in all those songs—earned a place in folklore as the ideal love nest for a young couple. House builders encouraged that line of thinking with a nudge and a wink, and added the helpful incentive that a bungalow for two could be built cheaply with an unfinished attic, and then, as nature took her course, two more bedrooms could be finished upstairs.

Nevertheless, cheapness was not always the main consideration. The bungalow was a fashion, and fashionable families might build fashionable bungalows that were every bit as expensive as more traditional houses, like this generously sized cement bungalow in Beechview, built in 1911 at a cost of about $4,000, which was above the average for Beechview houses, though many cheaper (and more vertical) houses had more living space.(1)

We hope we have given you, our hypothetical graduate student, enough inspiration to make the bungalow an attractive thesis topic. We eagerly await the results of your research.

Footnotes

- The Construction Record, June 3, 1911: “Plans have been completed for a 1½-story cement bungalow, to be erected on Crosby and Los Angeles streets, for Eugene E. Heard, 705 Penn avenue. Cost $4,000.” (↩)

One response to “Our Bungalow of Dreams”

[…] the most original composition on the street. It seems as though the architect was told, “I want a bungalow, but with three floors.” So that was what the client got: a mad bungalow with some sort of growth […]