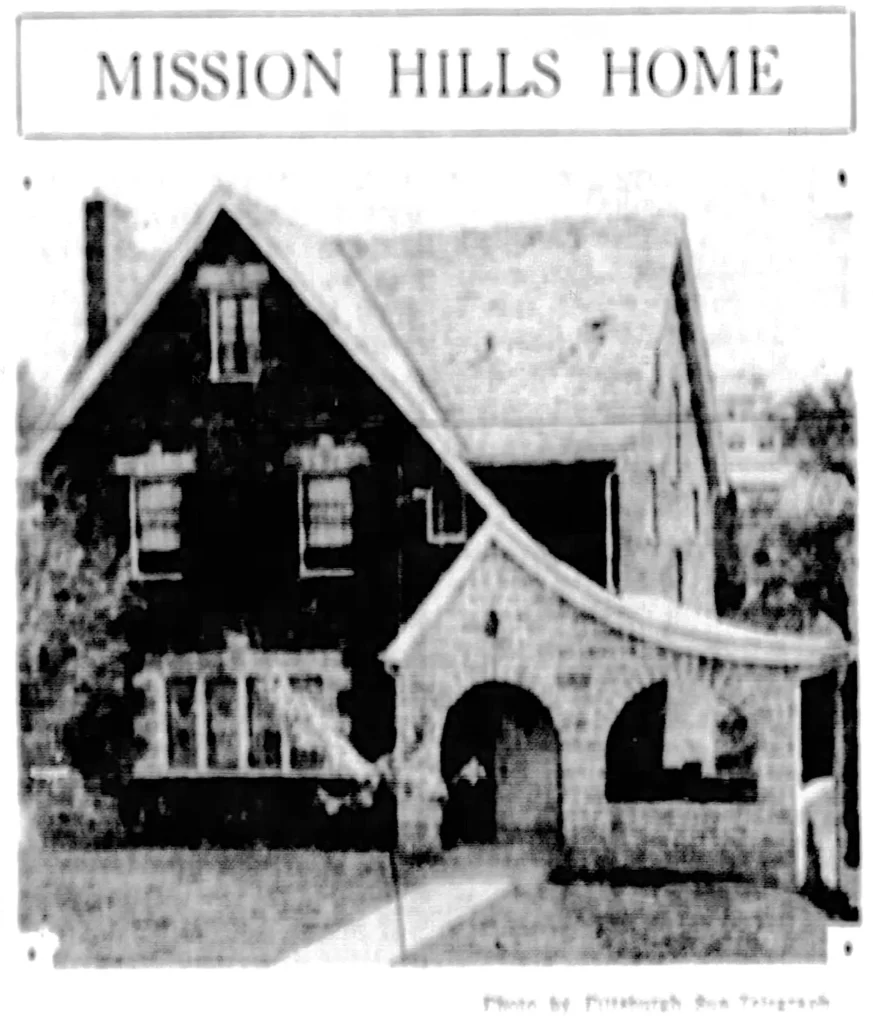

In the 1920s and 1930s, designers of houses often made them into fairy-tale cottages, in which every detail was carefully managed to evoke picturesque fantasies of old England or France. But this was also the time when built-in garages were becoming a requirement for suburban homes. If the garage door is on the front, it often spoils the fantasy. But this house in Mission Hills, Mount Lebanon, shows us that there is an alternative: make the garage part of the fantasy.

Not only is the garage entrance a big stone arch that suggests an immemorially ancient cellar under the house, but it is also decorated with the terra-cotta rays that were a fashionable adornment of the fairy-tale style.

Comments