If you have ever come up the Ohio or across the McKees Rocks Bridge, chances are you have noticed this gold-domed tower rising from the McKees Rocks Bottoms. You would not have had time to appreciate the details, but appreciate them now. Just the tower is a remarkable piece of work. But the whole church is something extraordinary, and worth a visit to the Bottoms to see. Since the Bottoms is a neighborhood of surprising architectural riches, you will probably find yourself distracted by a dozen other wonders before you leave.

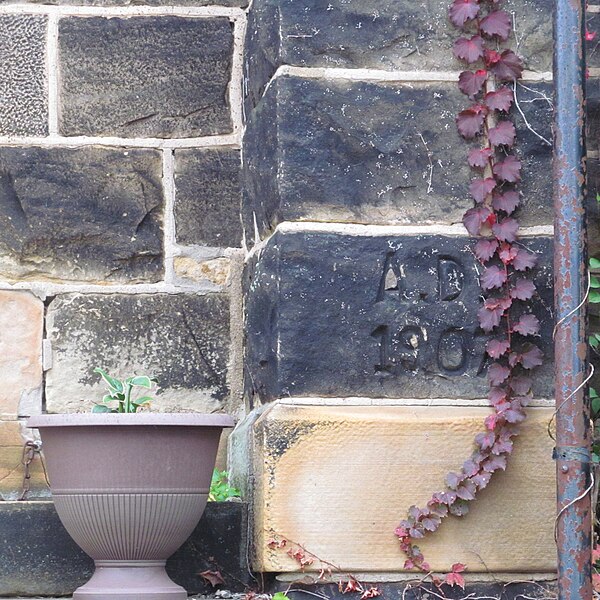

Holy Ghost Greek (now Byzantine) Catholic Church is a startling outcropping of Art Nouveau in a neighborhood where we never expected to find it. The design was the work of McKees Rocks’ own John H. Phillips, as we know from the cornerstone.

Here we have the date, the name of the architect, and the name of the contractor, along with the name of the pastor. There was one other church architect in Pittsburgh who routinely put his own name and the name of the contractor on cornerstones in florid Art Nouveau lettering, and that was Titus de Bobula. Looking at the style of this church, with its radical and constantly surprising Art Nouveau ornamentation, Father Pitt forms the hypothesis that Phillips knew of Titus de Bobula’s work and was strongly influenced by the eccentric Hungarian.

The corner cross picked out in bricks is wildly different from anything you have seen before. To the right of it we also see a variant of the square above a downward-pointing triangle that seems to have been a kind of signature for Phillips, appearing on at least three of the four buildings of his that Father Pitt has so far identified.

The church behind the front is more conventional—which is also true of Titus de Bobula’s churches. Both de Bobula and Phillips relied on elaborate fronts to make their grand impression.

Certainly this tower makes a strong impression. There is nothing else quite like it in Pittsburgh. The variation of detail in the bricks is remarkable. But the forms are harmonized very cleverly, with each level echoing shapes from the other two.

Phillips also designed the Ukrainian National Home around the corner, and Father Pitt hopes to identify more buildings by him in McKees Rocks. He has joined Pittsburgh’s exclusive little club of early modernists, and old Pa Pitt is delighted to make his acquaintance.