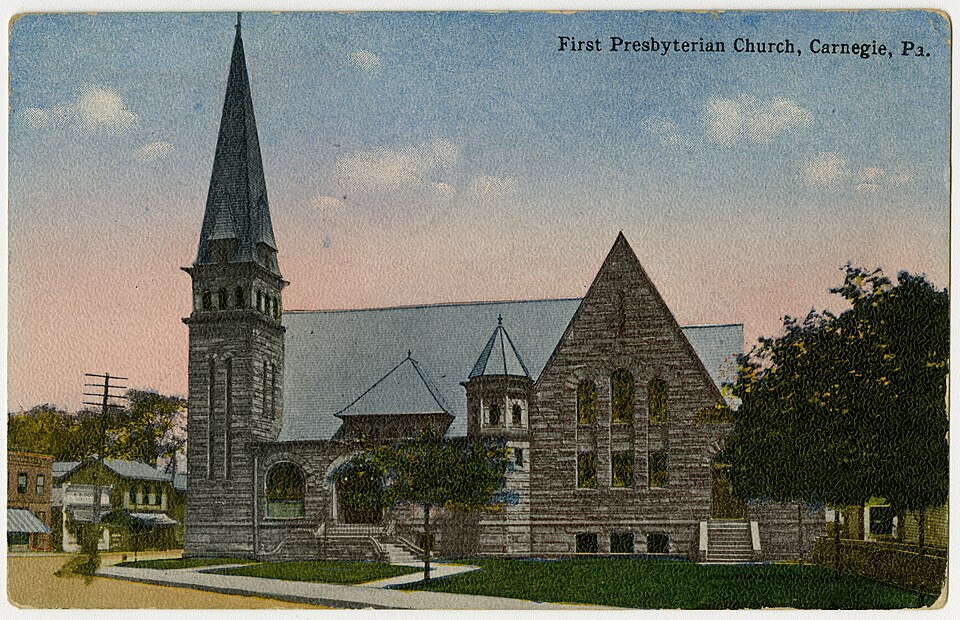

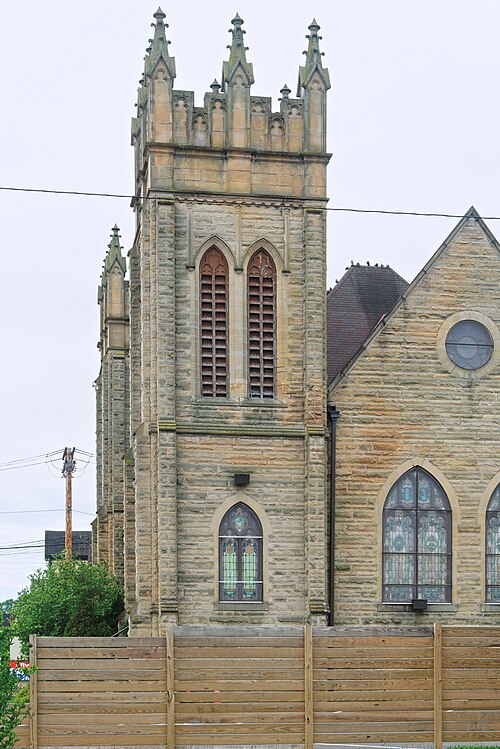

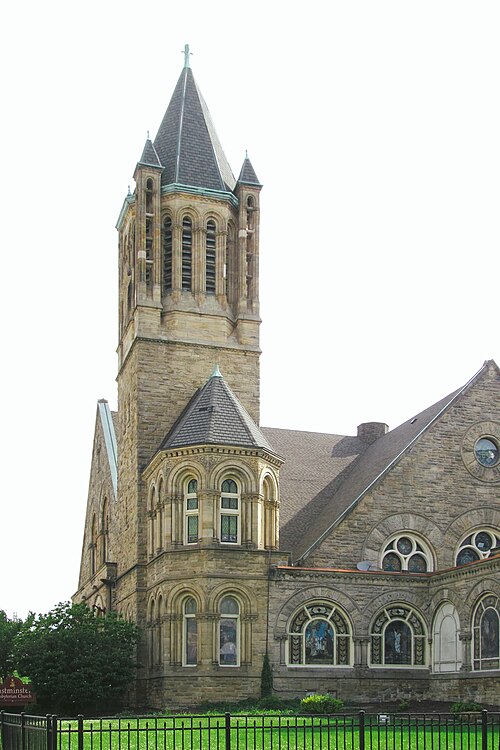

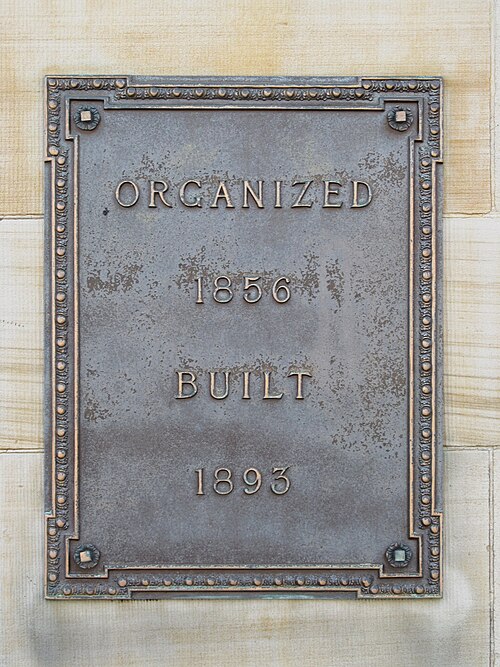

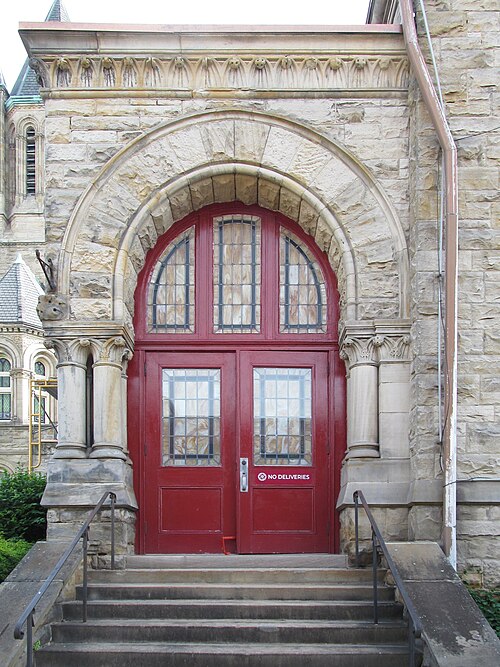

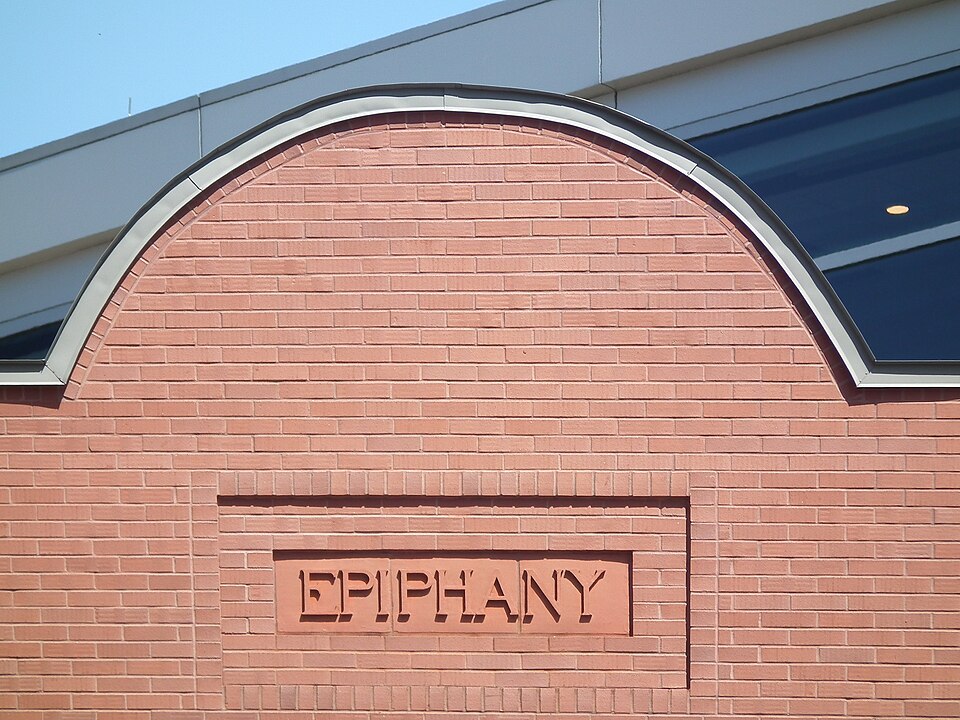

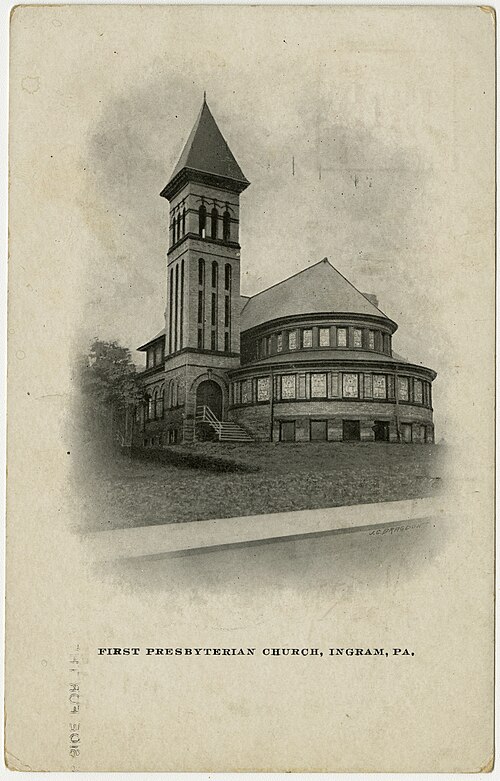

Built in about 1898, this church was designed by James N. Campbell,1 and it displays all the usual quirks of his style, including the corner tower with tall, narrow arches and the half-round auditorium made into the most prominent feature of the building: compare, for example, Beth-Eden Baptist Church in Manchester. It has been a Masonic hall for quite a while now. There are, however, still Presbyterians right across the street: the First United Presbyterian congregation was there, and the two denominations merged in 1959.

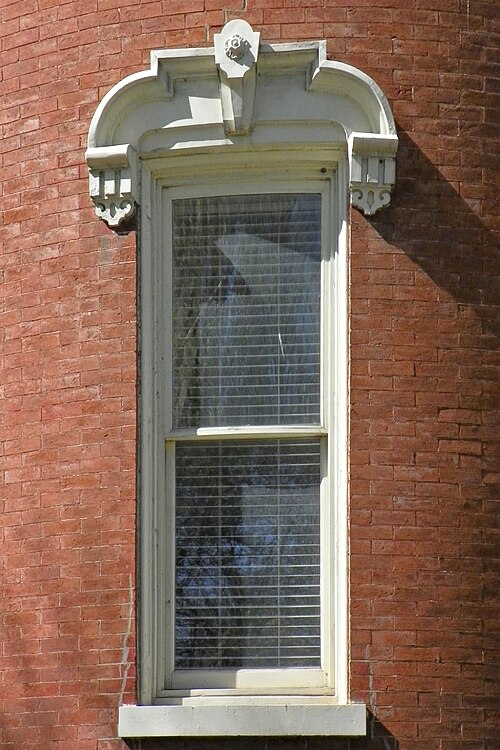

In this case the Masons have not blocked in most of the windows the way men’s clubs usually do when they take over a building. An old postcard from the Presbyterian Historical Society collection shows that the basement windows have been filled with glass block, and the open tower has been bricked in. But the stained glass is still intact through most of the church.

Comments