Steel baron B. F. Jones’ front doorway is a feast of elaborate terra cotta. This is a very large picture: enlarge it to appreciate the details of the terra cotta and ironwork.

Steel baron B. F. Jones’ front doorway is a feast of elaborate terra cotta. This is a very large picture: enlarge it to appreciate the details of the terra cotta and ironwork.

Warwick House was built in 1910 for Howard Heinz, son of the ketchup king H. J. Heinz. The architects were Vrydaugh & Wolfe, who designed several other millionaires’ mansions around here, as well as a number of fine churches. The house now belongs to the Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh, and it is rented to Opus Dei for a dollar a year, under the condition that the tenants undertake the maintenance, which is enormous.

Once a year the residents throw a big open house, which gave us a chance to get a few pictures. We would have got more, but we were having too much fun.

A French door in the back leading out into the garden.

The rear of the ballroom, an addition built in about 1929. It is now a chapel.

An arbor with some splendid ironwork runs along the back of the garden.

From an earlier visit, we also have several pictures of the interior of Warwick House.

Cameras: Kodak EasyShare Z1285; Fujifilm FinePix HS10. Most of the pictures are HDR stacks of three photographs at different exposures.

Old Pa Pitt had intended to place this picture with the rest of the pictures of Robin Hill the other day, but his automatic stitching software failed him. He had been reasonably careful in taking the three photographs so that they would line up nearly perfectly, but the stitching software produced a comical monstrosity reminiscent of Frank Gehry. What went wrong? Only because Father Pitt was stubborn enough to edit the “control points” himself—“control points” being identical features marked in two pictures, so that the software knows how to align them properly—did he discover the problem. The parade of identical windows was too much for the program. The extreme symmetry caused it to identify this window as the same as that window, which caused the whole building to collapse in a heap.

So old Pa Pitt stubbornly picked out all the control points himself, and produced a nearly perfect rendering of the garden side of the mansion. Stubbornness is a character flaw, but it has its uses.

Robin Hill was designed for Francis and Mary Nimick by Henry Gilchrist. He gave them a classic Georgian country house, and, like many country houses, it is really meant to be enjoyed from the garden side.

The house was built in 1926, and for nearly half a century the Nimicks enjoyed it. When Mary died in 1971, she willed the whole estate to the township to be preserved as a park.

The front of the house presents a dignified appearance to the visitor.

Cameras: Kodak EasyShare Z981; Sony Alpha 3000; Konica Minolta DiMAGE Z6.

An elegant Tudor or Jacobean mansion designed by MacClure & Spahr and built in 1903, as the dormer tells us. This Post-Gazette story (reprinted in a Greenville, North Carolina, paper that does not keep it behind a paywall) tells us that a 1925 addition was designed by Benno Janssen, who had worked in the MacClure & Spahr office and may have had some responsibility for the original design. The article also tells us how vandals masquerading as interior designers rampaged through the house and painted all the interior woodwork white or pale grey to “banish dark wood,” but at least the exterior is in good shape.

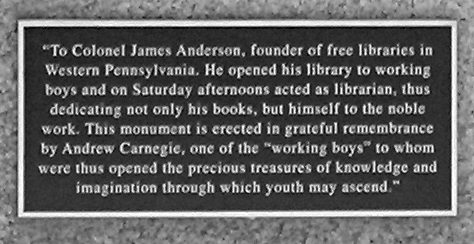

Few of the great Greek Revival mansions that surrounded Pittsburgh before the Civil War have survived. This one has, and that alone would make it important. But this one also has a place of high honor in the intellectual history of the United States. This was the home of Colonel James Anderson, the book-lover, who opened his personal library to working boys on Saturday afternoons. One of those boys was Andrew Carnegie, who attributed his later success to the education he got from reading Col. Anderson’s books. When Carnegie established his first public library in Allegheny, he donated a memorial to Col. Anderson to stand outside and remind the city that Carnegie was only following his benefactor’s example. A plaque, set up by somebody who did not understand how quotation marks work, duplicates the original inscription:

The original house was built in about 1830; additions were made in 1905—a fortunate time, since classical style had come back in fashion, and the additions were in sympathy with the original.

The house has belonged to various institutions over the years, but many of the details remain intact.

The colonnaded porch-and-balcony has Doric columns below, Ionic above—a scrupulously correct treatment. Doric was regarded as weightier than Ionic, so the lighter-looking columns are supported by the heavier-looking ones. If there were a third level, the columns would be Corinthian, the lightest of the three Greek orders.

The Byers-Lyons house was built in 1898. It was designed by Alden & Harlow, Andrew Carnegie’s favorite architects, and it has fortunately been preserved by being turned to academic uses—it is now Byers Hall of the Community College of Allegheny County. It looked warm and inviting last night at sunset, so Father Pitt took quite a few pictures.

Virginia Manor is where the rich rich people live in Mount Lebanon. It’s full of houses designed by some of the most distinguished Pittsburgh architects of the 1920s and 1930s. Osage Road has some of the grandest houses, so here is your look at how the other half lives—unless you are the other half, in which case here is your hand mirror.

This grand mansion was built in about 1890 for railroad magnate Harry Darlington. It occupies a tiny lot, so it is one room wide—but four storeys tall and half a block deep.

The building is decorated with numerous terra-cotta tiles with fine scrolly foliage.

A carriage house in the back has matching stony foundations.