The sun was glaring and the shadows were deep, but as far as old Pa Pitt knows, these composite photographs are the only complete elevations of the Park Building on the Internet. Above, the Smithfield Street face; below, the Fifth Avenue face.

And, of course, the most striking feature of the building: the telamones that hold up the roof.

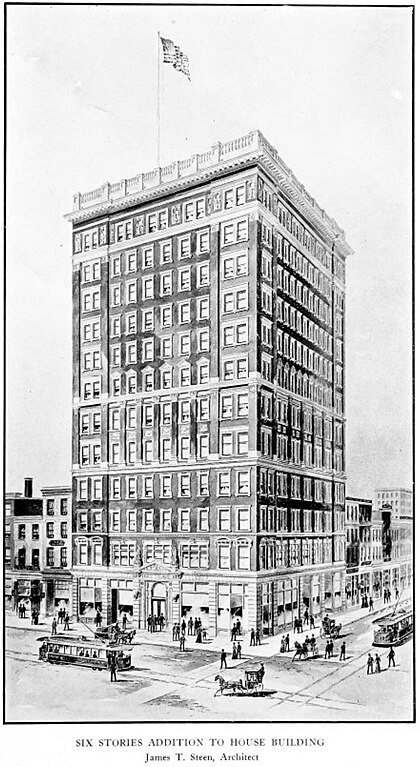

The Park Building, built in 1896, is Pittsburgh’s oldest extant skyscraper. (The Carnegie Building, demolished in 1952, was a year earlier.) George B. Post of New York was the architect, and he designed it in the florid Beaux Arts style that would also be usual in the earliest New York skyscrapers. Although it was damaged decades ago by an ill-conceived modernization, the basic outlines and much of the ornament are intact. It displays all the attributes of an early New York skyscraper—the attributes that became dogma for early skyscrapers across the country. (See “The Convention in Sky-Scrapers.”) And with good reason: a bunch of these skyscrapers may create a certain monotony in the skyline, but following the Beaux Arts skyscraper formula reliably produces a good-looking building.

“Form follows function,” as Louis Sullivan said. Modernist architects used that saying as a slogan (which probably annoyed Mr. Sullivan) meaning that the form of a building should express the structural functions of the parts. But the form of a Beaux Arts skyscraper expresses the social functions of its parts: it makes visible what different parts of the building do, in a way that modernist architecture often fails to accomplish.

The basic formula for early skyscrapers is base, shaft, and cap. “A convention of treating them as columns with a decorated capital, a long plain central shaft, and a heavier base, was early adopted,” as the Architectural Record said in 1903.

The base—usually the first two floors—is the public part of the building, where retail shops or banking halls and such things are located—where, in short, the public interacts with the main business of the building.

The shaft, which is usually a repeating pattern of windows and wall, is where the ordinary business offices of the skyscraper are located.

Up in the stratospheric heights of the cap are the very most important people—the princes of commerce, and the lackeys and flunkeys who attend to their needs.

Now look at the Park Building, and you will see that the third floor, though more or less part of the shaft, is outlined and set apart from the rest. This is the bosses’ floor, in which the important men who supervise what goes on downstairs are located.

Just by looking at the face of the building, you can tell what goes on in each of its parts, which is not true of a modernist glass box. Here the social functions of each floor are made visible in stone and brick. Although the form is not structural, in a human sense this is form following function.