Nearest to farthest: Liberty Bridge, Panhandle Bridge, Smithfield Street Bridge, Fort Pitt Bridge, West End Bridge.

Nearest to farthest: Liberty Bridge, Panhandle Bridge, Smithfield Street Bridge, Fort Pitt Bridge, West End Bridge.

The Gulf Tower is one of those buildings of the style old Pa Pitt calls “Mausoleum-on-a-stick,” where a skyscraper ends in a top modeled after the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. Trowbridge and Livingston, who designed the Gulf Tower (with Edward Mellon as local architect of record), were the originators of the style, as far as Father Pitt can determine: the Gulf Tower is a Moderne reimagining of their original Mausoleum-on-a-Stick, the Bankers Trust Company Building on Wall Street, New York.

As Father Pitt has remarked before, telephone exchanges were designed to be ornaments to their neighborhoods, and the Renaissance-palace style was one of the most popular forms for them. This one is on Main Street in Sharpsburg, and it preserves its Renaissance dignity under the ownership of the successor to the Bell System.

This blank wall on the western end of the building shows two different colors of bricks, suggesting that the building was originally one storey, with the second storey added later. That would explain the cornice at the first-floor level.

Map.

The big blue “CONDEMNATION” sticker appeared on a fine Italianate rowhouse in the 1100 block of Sarah Street a while ago, and old Pa Pitt decided to document the house before it vanished. You can imagine how delighted he was to find that the blue sticker is gone and the house is under renovation, with new windows installed already.

Nothing can stop a contractor from installing Georgian-style fake “multipane” windows, which contractors think of as the mark of quality, even when they are completely inappropriate for the style of the house, and even when the “panes” are false divisions made by laying a cartoon grid over a single sheet of glass. But at least these windows are the right size for the holes, and therefore no lasting damage has been done. Father Pitt would guess that a house like this originally had two-over-two windows: see, for comparison, this house of similar age Uptown.

The woodwork is a bit tattered, but we hope it can be preserved.

This transom is crying out for an address in stained glass. Emerald Art Glass is only a dozen blocks away.

Of course Father Pitt could not leave without documenting this fine breezeway.

Like the windows, the front door is a standard model that fits properly and could be replaced with a more appropriate style later by a more ambitious owner.

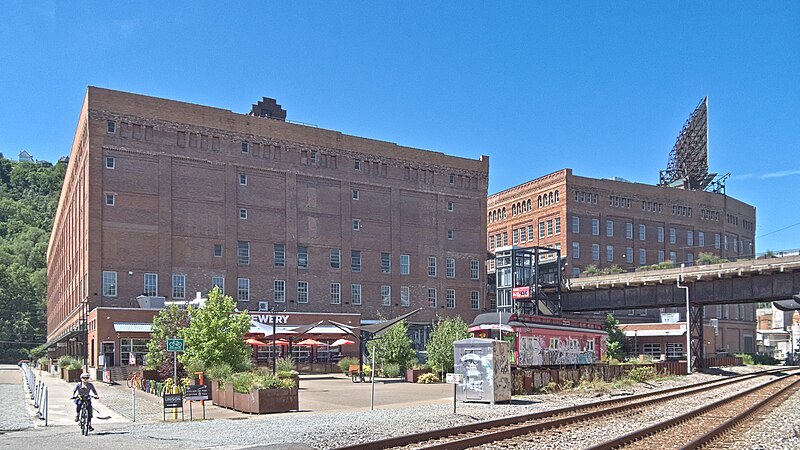

Now called “The Highline,” the Pittsburgh Terminal Warehouse and Transfer Company was one of the largest commercial buildings in the world when it was finished in 1906. The architect was the prolific Charles Bickel, who gave us a very respectable version of Romanesque-classical commercial architecture on a huge scale.

The building was planned in 1898, but it took several years of wrangling and special legislation to clear three city blocks and rearrange the streets to accommodate the enormous structure. Its most distinctive feature is a street, Terminal Way, that runs right down the middle of the building at the third-floor level: as you can see above, it has now been remade into a pleasant outdoor pedestrian space. You can’t tell from the picture above, but there is more building underneath the street.

The bridge coming out across the railroad tracks is the continuation of Terminal Way, which comes right to the edge of the Monongahela, where the power plant for the complex was built.

The reason for the complex is more obvious from this angle. Railroad cars came right into the building on the lowest level to unload.

It also had access to the river, and road access to Carson Street at the other end. Every form of transportation came together here for exchange and distribution.

McKean Street separates the main part of the complex from the Carson Street side; Terminal Way passes over it on a bridge.

The Fourth Street side shows us the full height of the building. Fourth Street itself is still Belgian block.

A view over the McKean Street bridge and down Terminal Way from the Carson Street end.

This absurdly narrow building is on the Carson Street side of the complex; it has usually housed a small restaurant of some sort. One suspects that this was the result of some kind of political wrangling that ended in a ridiculously small space on this side of Terminal Way between Carson and McKean Streets.

The power plant for the complex, seen above from the Terminal Way bridge across the railroad. It could use some taking care of right now.

This view of the complex from the hill above Carson Street was published in 1911 as an advertisement for cork from the Armstrong Cork Company.

The Ninth Street or Rachel Carson Bridge: above, from the Downtown end; below, from the end of the Seventh Street or Andy Warhol Bridge.

The German National Bank—now the Granite Building—is one of the most ornately Romanesque constructions ever put up in a city that was wild for Romanesque. The architect was Charles Bickel, but much of the effect of the building comes from the lavish and infinitely varied stonecarving of Achille Giammartini, Pittsburgh’s favorite decorator of Romanesque buildings.

We have sixteen more pictures in this article, and this is only a beginning. Old Pa Pitt will have to return several more times with his long lens to document Giammartini’s work on this building.

(more…)

More views of the old Gimbels warehouse on the South Side, now called 2100 Wharton Street. We have a couple of other angles here.

The building covers almost the entire block, but leaves a narrow space for one row of old houses at the eastern end on 22nd Street.