Once again our frequent correspondent David Schwing has spotted something important and delightful: a previously unidentified work by Elise Mercur, Pittsburgh’s first female architect. It’s been sitting right there in the open, but nothing on the Internet has pointed out its significance.

Mercur was a fascinating character. At a time when women as architects were almost unheard of, she was getting big commissions and supervising crews of men who knew they had better not cross her. (See the picture above: would you want to get that look from your boss?)

She first came to national attention when she beat twelve other competitors with her design for the Woman’s Building at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895. The decision of the committee was unanimous: she blew the other competitors away.

These renderings were printed in a big architectural magazine, which picked them up from another big architectural magazine. They were also front-page news in Atlanta, and of course in Pittsburgh. The Inland Architect and News Record accompanied them with this brief introduction to the architect:

Miss Elise Mercur, architect, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Of thirteen designs submitted, hers was considered of the highest merit and was accepted. As a preparation for her professional life Miss Mercur studied four years at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts and subsequently continued her artistic studies in Germany. The lady has been a resident of Pittsburgh for four years and has been engaged upon practical architectural work in the office of Architect Thomas Boyd, whose foreman she now is. Miss Mercur assisted in the preparation of the plans for the new city Poor Buildings at Marshalsea and superintended their erection.

Thomas Boyd was a very prosperous architect in those days, and we must give him credit for recognizing ability when he saw it. It took courage to make a woman his construction foreman, but Mercur was up to the task.

Soon she had a prospering practice of her own, and she insisted on being in every way equal to a male architect.

For doing men’s work I always insist upon getting men’s prices. I never accept an assignment for less than 5 per cent. I never have any trouble. Contractors who have worked under me know that I won’t stand any ‘monkeying’ and do not try to fool me with poor material, careless work, &c. While I am willing to do what is right, I generally make them live up to the specifications, and any work done improperly has to be gone over again. (Mercur quoted in “Pittsburg’s Woman Architect,” New York World, January 9, 1898.)

Much of her work was academic—dormitories and classroom buildings for colleges. And that explains why most of it is gone. College presidents hate old buildings, because they stand in the way of big donors’ vanity projects, and college presidents are generally hired for their ability to round up big donors, not for their sensitivity to the architectural heritage of the campus. As far as we know, all of Mercur’s academic buildings have been demolished, some fairly recently. In fact, until a little while ago the only remaining building by Mercur known to exist was St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in the Hill District. But now we have a fine house whose identification rests on solid ground.

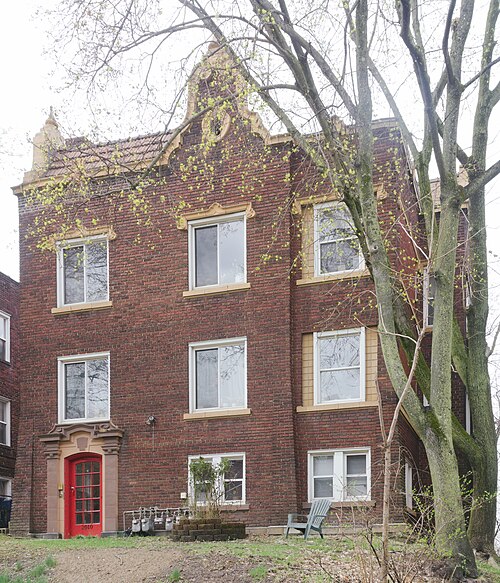

Dr. William H. Mercur has purchased a choice plot on Fifth avenue, opposite Lilac street, as a site for a new home. The lot measures 50×200 feet, and it belonged to Charles D. Callery. The price paid was $10,000 cash, or $200 a foot. Mrs. Elsie Mercur-Wagner is making plans for a $15,000 brick dwelling which is to be erected on the property within the next few months. (“Real Estate Transactions,” Pittsburg Press, April 27, 1900, p. 14.)

By this time Mercur was married and using the name Wagner along with her own. We may point out in passing that the name “Elise” was unusual enough that almost half the construction listings misspell it as “Elsie.” Dr. William H. Mercur was her brother, and we imagine he was quite pleased with the house his sister built for him.

“Lilac Street” in the listing is now St. James, and the location “opposite Lilac street” makes the house easy to find. Plat maps shortly after the house was built show it as belonging to M. S. Mercur (probably William’s wife; property was often put in the name of the wife). In 1923, it still belonged to M. S. Mercur. It is on the side of Fifth Avenue that is counted as Squirrel Hill by city planning maps, but traditionally both sides of the street were “Shadyside,” and the Mercurs were rubbing elbows with some very rich people in the Shadyside millionaires’ row.

By comparing this lot with the one next to it, we can see that the lot level was originally above the garage doors. The front yard has been dug away to make space for driveway and garages. Much of the distinctive detail of the house has been preserved, however, and we hope the owners realize that they possess a rare treasure.

Comments