This stairway at the end of 15th Street, South Side, takes pedestrians up to a bridge over the railroad, and then to a stairway up into the South Side Slopes.

The double arch inside a single arch, with a circle to fill in the gap, is characteristic of the style of classically influenced Romanesque the Germans called Rundbogenstil, the round-arch style. It may not be exclusive to the Rundbogenstil, but Father Pitt likes to say the word “Rundbogenstil.” The B. M. Kramer and Co. building on the South Side, built as a beer warehouse, is one of the masterpieces of industrial architecture in Pittsburgh.

Aluminum, vinyl, Insulbrick, and Perma-Stone: old Pa Pitt calls them the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. They are the four most common artificial sidings applied to Pittsburgh houses, especially frame houses. (But not exclusively frame houses: siding salesmen were aggressive enough to go for brick houses if they sensed weakness in the buyer.) They are responsible for more uglification in the city than any other single force. That is not to say that it is impossible to use them well, only that they are almost never used well. We can find perfect illustrations within a block of each other on the South Side.

Aluminum is usually easy to recognize by the rust stains, which probably come from the fasteners rather than the aluminum itself.

Vinyl siding is the closest in appearance to wood siding, and if applied well can be hard to distinguish from a distance. But instead of removing the wood siding and replacing it with vinyl, the contractors usually stick the vinyl over the wood siding. That means two bad things: first, that there is an invisible layer of decaying wood; second, that all the trim on the house is swallowed up, leaving the house a cartoon shell. In the picture above, the whole process has been taken to its logical conclusion in the right-hand house. A good deal of money was spent on new windows in the wrongest possible shapes, vinyl trim, and paste-on fake shutters that could not possibly cover the windows, leaving the house an expensive architectural wreck.

Insulbrick is a trademark name (though there were disputes over the trademark) for siding made up of asphalt sheets stamped with a brick pattern. When the siding is new, it looks as if a child drew bricks on the house with crayons. When it is older, it looks like the picture above. In spite of the name, it is very bad at insulating.

Perma-Stone is another trademark name: it is siding that imitates stonework, once again in a cartoonish fashion.

Sometimes more than one of these sidings can grow on a house, either because the owner loved variety, or because different generations attacked different maintenance problems in different halfhearted ways.

Insulbrick and vinyl.

Aluminum and Perma-Stone.

If you are the owner of a frame house that still has wooden siding, congratulations! You are a member of a small elite minority in Pittsburgh. Keep a good coat of paint on that siding, and attack problems while they are still young, and you will keep your house beautiful for generations to come.

If the time comes to replace that siding, though, consider the long term. Contractors will tell you that their artificial sidings will last forever. Look around you. You can see that they are misinformed. Consider replacing wood with wood, or—if wood is not in your budget—consider replacing it with vinyl rather than covering it over with vinyl.

Except for the inevitable distortion of the towers, this is a very accurate rendition of the front of St. Adalbert’s on the South Side. (The distortion is the result of using many photographs to construct what amounts to an impossibly wide-angled rectilinear lens to get the whole front across a very narrow street.) Built in 1889, this church served generations of Polish Catholics, and still serves the congregation of Mary, Queen of Peace parish. The architect does not seem to be known, but old Pa Pitt would be delighted to be informed if anyone does know who it was.

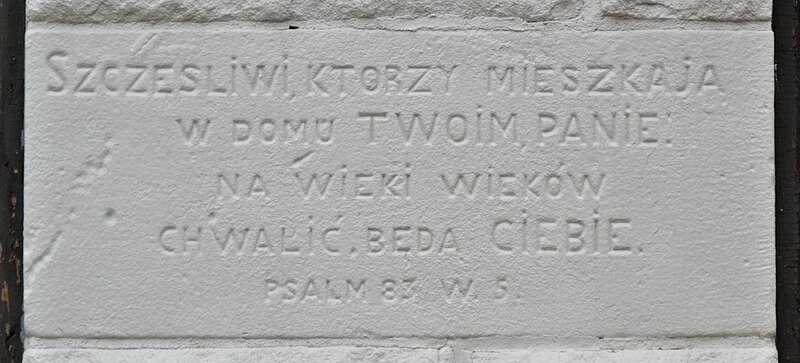

Psalm 83:5 in the Vulgate numbering (Psalm 84:4 in Protestant and more recent Catholic versions): “Blessed are they that dwell in thy house, O Lord: they shall praise thee for ever and ever.”

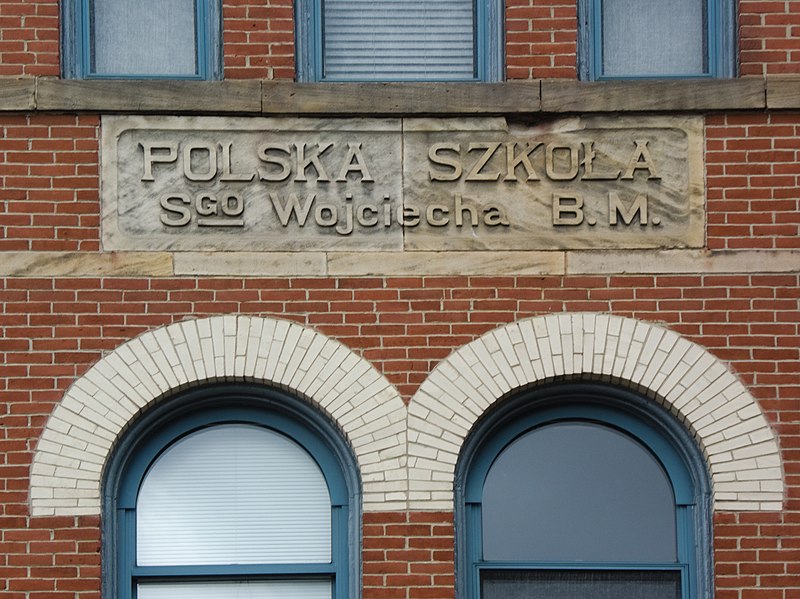

Father Pitt does not know much Polish, but this inscription honors the efforts of Fr. Wladislaw Miskiewicz, parish priest.

The church dominates the back end of 15th Street, one of those absurdly narrow streets in old Birmingham. This is the view from the steps up to the 15th Street pedestrian overpass that leads across the railroad tracks to the Slopes. This end of 15th Street was a whole village of Polish Catholic institutions.

St. Adalbert’s convent.

The rectory.

The Polish school.

We also saw the mid-twentieth-century auditorium, now being turned into condominiums.

Carson Street is famous for its Victorian commercial buildings, but here and there among the Victorian masterpieces, and the later fillers, are a few that we might call pre-Victorian. Even though they were built during the long reign of Queen Victoria across the sea, these buildings betray little of the style that we think of as Victorian. They are hardly architecture at all. They are built in the simple vernacular style that was current for decades in the early and middle nineteenth century—and had indeed been inherited from the eighteenth. They are identical to houses of the same era, except with the front of the first floor modified into a storefront.

Here are two of them. Both of them have been through various alterations over the years, but they are easily recognized by their peaked roofs with narrow projecting dormers, making them look almost like a child’s drawing of a house. From our 1872 map, it seems fairly certain that both of them were here in 1872, when East Birmingham was taken into the city of Pittsburgh; they probably date from the period of rapid development in East Birmingham during and right after the Civil War.

“When life hands you lemons,” as the old saying goes, and here is an example of someone making pretty good lemonade out of some very unpromising lemons.

Three years ago the old St. Adalbert’s Auditorium looked like this.

Obviously it had been abandoned, and desultory attempts at maintenance had ground to a halt. This in spite of the fact that the church right next door was still active, and indeed still is today.

But now the same developer who converted St. Casimir’s to condominiums has taken this building in hand, turning it into fairly expensive condominiums under the name “The Auditorium.”

A sign in front tells us that nine out of fourteen units have already been sold. Considering that the building was a gymnasium, auditorium, and fallout shelter built in the most undistinguished modernist style, this is a very good outcome for a building that had been a festering eyesore in the neighborhood.

It was not really a black-and-white camera; it was old Pa Pitt’s nineteen-year-old Samsung Digimax V4, a strange beast that was made for photography enthusiasts who wanted something that would fit in the pocket but still had most of the options of a sophisticated enthusiast’s camera. Father Pitt has set the user options to black-and-white. There is no good reason for doing so: obviously the camera collects color data and throws the colors away, and the colors could just as well be thrown away in software after returning from the expedition. But knowing that the picture must be black and white forces one to think in terms of forms rather than colors. So here are half a dozen pictures from a walk through the South Side Flats.

These buildings were put up in the 1880s, with additions in the 1890s; they later became part of the United States Glass Co. More recently the South Side was associated with steel, but in 1872, when the Birminghams, South Pittsburgh, and Ormsby were taken into the city, glass was at least as important. Just looking at the 1872 map, we find—

Knox Kim & Co. Glass Works

Est. of Wm. McCully Glass Works

Pittsburgh Glass Works

Bakewell, Pears & Co. Glass Works

Whitehouse Flint Glass Works

Doyle & Co. Glass Works

Adams & Co. Glass Works

Tremont Glass Works

C. Ihmsen & Sons Glass Works

McKee & Bro. Glass Works

Bryce, Walker & Co. Glass Works

Sl. McKee & Co. Glass Works

A. King Glass Works

We have probably missed a few, but the list is quite enough to show us that glass was a big deal on the South Side. Of all the old glass factories, this is probably the only one left in such a splendidly original state, if any of the others remain at all.

These three buildings date from before 1872, since they appear on our 1872 map. The two exceptionally large houses on the left look like Civil War engravings of street scenes. Some of the details, like the gutters, have changed, but the overall appearance is very 1860s. The smaller frame house on the right has suffered every external indignity a house can suffer, but the simple shape with narrow projecting dormer still says middle 1800s.