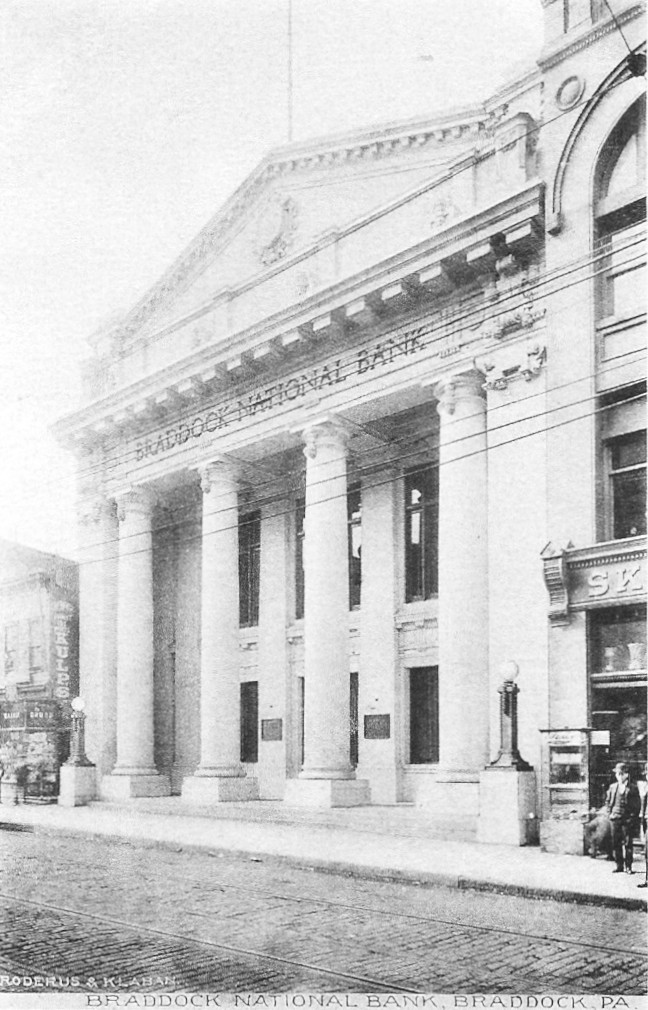

A brick sidewalk in Allegheny West laid with grey Kittanning bricks. That is rare: most sidewalks in Pittsburgh were made with cheap red bricks. Kittanning bricks were special, generally used for facing buildings; in fact, we often see buildings with buff brick on the front, and cheaper red brick for the side and rear walls that no one is supposed to see.

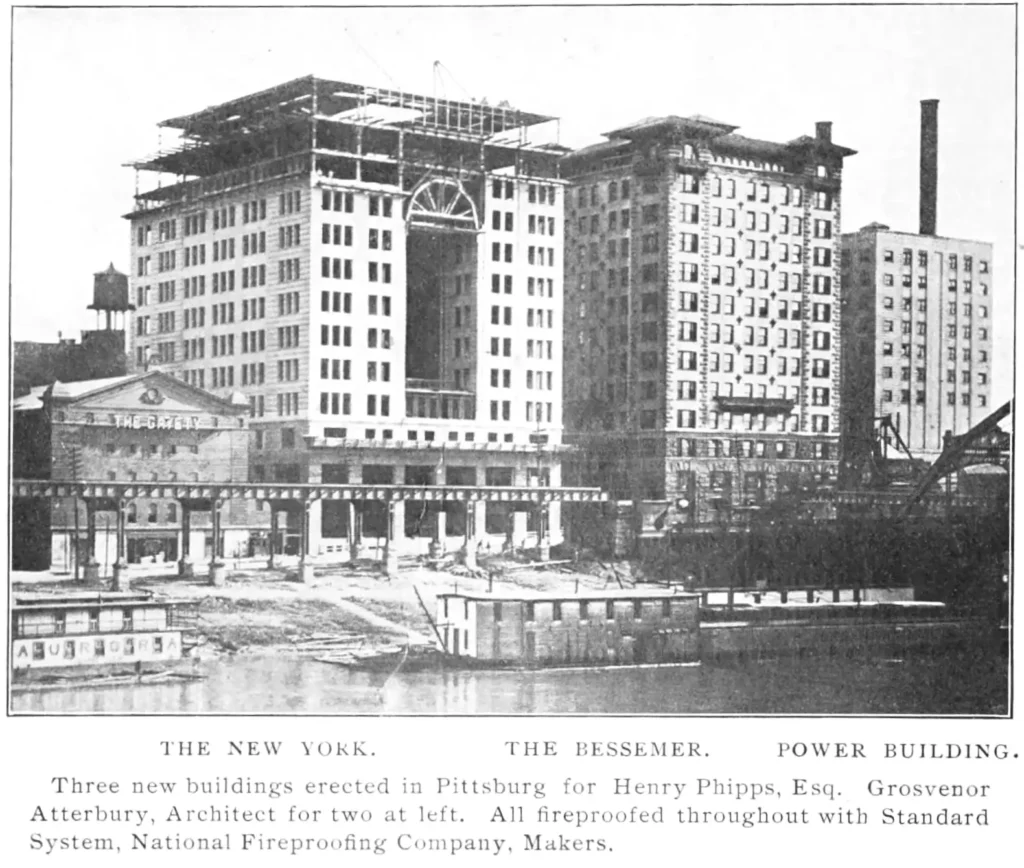

In the East Coast cities, bricks are red. There are exceptions, mostly high-budget constructions: the Naval Academy in Annapolis, for example, makes extensive use of white brick. But it is striking to East Coasters when they come to Pittsburgh to see that bricks come in a multitude of colors. These are the famous Kittanning bricks, and the leading—though by no means the only—producer of them was the Kittanning Brick Company. They were used more extensively in Pittsburgh and the surrounding area than anywhere else, which is why a street of brick houses in Pittsburgh may be a rainbow of red, buff, grey, and white bricks.

In 1912, the Congressional Committee on Rivers and Harbors held hearings “On the Subject of the Improvement of Allegheny River, Pennsylvania, by the Construction of Additional Locks and Dams.” Mr. S. E. Martin, one of the titans of the brick industry in Kittanning, was invited to give testimony. Note, incidentally, that in the trade the plural of “brick” was “brick.”

Mr. PORTER. I now desire to introduce Mr. S. E. Martin, who represents some brickkilns along the Allegheny River, and the brick interests in general in what is known as the Kittanning district.

STATEMENT OF MR S. E. MARTIN, OF KITTANNING DISTRICT, PA.

Mr. MARTIN. Mr. Chairman and gentlemen, Mr. Porter informs me that the time is a little short, and I wish just simply to present to you an outline of the brick interests as they are represented in what we will term the Kittanning district.

In this district that will be affected by this proposed improvement there are eight or nine companies manufacturing brick between Templeton and White Rock. An estimate of their combined output is approximately 170,000,000 brick.

Now, this brick is not common brick, but face brick—brick that are used for facing buildings of all kinds. It makes an approximate tonnage of about 500,000 in the finished product. This brick, known as the Kittanning brick (which is a gray brick or a buff brick in different shades), can be manufactured only from the clay in this district. It has been proven that this clay does not exist outside of this immediate vicinity, and this clay has made a brick that has popularized itself all over the country.

The CHAIRMAN. What is the name of that brick?

Mr. MARTIN. Kittanning.

Mr. BARCHFELD. Is the Plaza Hotel in New York built of that brick?

Mr. MARTIN. Yes, sir.

The CHAIRMAN. You say it is the only clay in the world from which that brick can be made?

Mr. MARTIN. There is no clay that I know of that will manufacture the same brick.