We saw the movie version yesterday, and now here are two still pictures of the vigorously moving Saw Mill Run at Seldom Seen.

And here is a picture of the path leading toward the Arch and the railroad viaducts:

We saw the movie version yesterday, and now here are two still pictures of the vigorously moving Saw Mill Run at Seldom Seen.

And here is a picture of the path leading toward the Arch and the railroad viaducts:

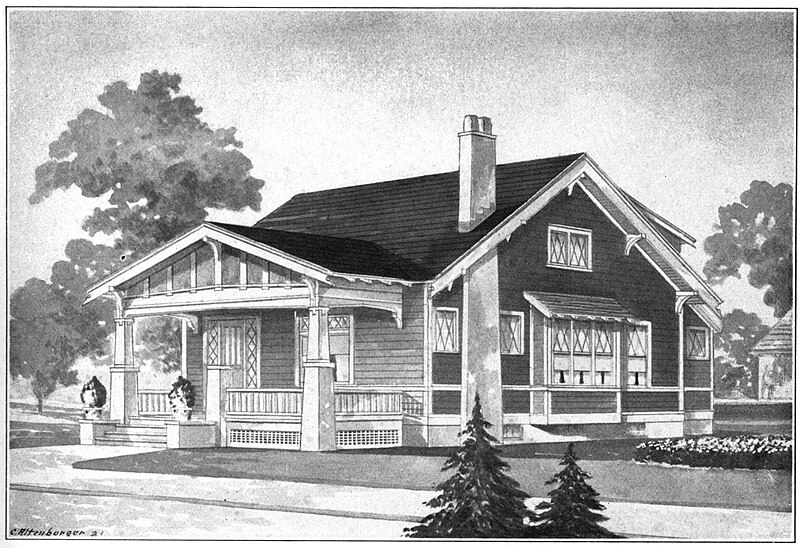

Here is a bungalow from the book Pennsylvania Homes, published in 1925 by the Retail Lumber Dealers’ Association of Pennsylvania, which had its headquarters in the Park Building in Pittsburgh.

Some graduate student right now is probably writing a thesis on “The Idea of the Bungalow in Early-Twentieth-Century American Thought.” Certainly there is enough material for a hefty academic treatise. We could probably write a thick book just on the cultural implications of 1920s song titles: “Our Bungalow of Dreams,” “We’ll Build a Bungalow,” “A Little Bungalow,” “A Cozy Little Bungalow” (that’s a different song), “There’s a Bungalow in Dixieland,” “You’re Just the Type for a Bungalow.” And so on.

A “bungalow” in American usage was a house where the rooms were all on the ground level, though often with extra bedrooms in a finished attic. It was the predecessor of the ubiquitous ranch houses of the 1960s. It was associated with the “Craftsman” style promoted by Gustav Stickley and others. Low-pitched roofs, overhanging eaves, and simple arts-and-crafts ornament were typical of the style.

What caused American houses to go from predominantly vertical to predominantly horizontal? We will not attempt to answer that question definitively; we have to leave our hypothetical graduate student some material for a thesis. We only offer some suggestions.

First, there are practical advantages to a one-level design. Advertisements often dwell on the number of steps the bungalow saves the busy housewife, which reminds us that middle-class families were beginning to consider the possibility of getting along without servants.

Second, a small bungalow could be built very cheap. It is true that a rowhouse could be built even cheaper, but the bungalow offered the privacy of a detached house. Some of these bungalows were extraordinarily tiny: that book of Pennsylvania Homes featured a “one-room” bungalow, with a tiny kitchen, dressing room, and bathroom, and one “great room” that could become a pair of bedrooms at night by drawing a folding partition across the middle. Most were not quite so tiny: a typical bungalow had a living room, dining room, kitchen, bathroom, and one or two bedrooms on the ground floor.

Third, there was the suburban ideal. In the early twentieth century, Americans were persuading themselves that what they wanted was the country life, but with city conveniences—in other words, the suburb. The city did not always have room to spread out horizontally, but the suburbs were more encouraging to horizontality.

Fourth, the bungalow—as we see in all those songs—earned a place in folklore as the ideal love nest for a young couple. House builders encouraged that line of thinking with a nudge and a wink, and added the helpful incentive that a bungalow for two could be built cheaply with an unfinished attic, and then, as nature took her course, two more bedrooms could be finished upstairs.

Nevertheless, cheapness was not always the main consideration. The bungalow was a fashion, and fashionable families might build fashionable bungalows that were every bit as expensive as more traditional houses, like this generously sized cement bungalow in Beechview, built in 1911 at a cost of about $4,000, which was above the average for Beechview houses, though many cheaper (and more vertical) houses had more living space.

We hope we have given you, our hypothetical graduate student, enough inspiration to make the bungalow an attractive thesis topic. We eagerly await the results of your research.

It sounds like a good name for a 1930s Warner Brothers musical, but we’re talking about the Broadway in Beechview, where the streetcars still run on the street. One of the characteristic forms of cheap housing in Pittsburgh streetcar neighborhoods is the rowhouse terrace, where a whole row of houses is built as one building. “This method of building three or six houses under one roof shows a handsome return on the money invested,” as an article about the Kleber row in Brighton Heights put it. In other words, here is a cheap way to get individual houses for the working classes.

Architecturally, it poses an interesting problem. How do you make these things cheap without making them look cheap? In other words, how do you make them architecturally attractive to prospective tenants?

In the row above, we see the simplest and most straightforward answer. The houses are identical, except for each pair being mirror images, which saves a lot of money on plumbing and wiring. The attractiveness is managed by, first of all, making the proportions of the features pleasing, and, second, adding some simple decorations in the brickwork.

Architects (or builders who figured they could do without an architect) often repeated successful designs for cheap housing, making it even cheaper. A few blocks away is an almost identical row.

The wrought-iron porch rails are later replacements, probably from the 1960s or 1970s, but the shape, size, and decorative brickwork are the same, except that here we have nine decorative projections along the cornice instead of five.

Now here is a different solution to the terrace problem:

Here we have two rows of six houses each. Once again, the houses are fundamentally identical, except for half of them being mirror images of the other half. But the architect has varied the front of the building to make a pleasing composition in the Mission style, which was very popular in the South Hills neighborhoods in the early 1900s. Instead of a parade of identical houses, we get a varied streetscape with tastefully applied decorations that are very well preserved in these two rows.

Incidentally, terrace houses like these look tiny from the front, but they often take full advantage of the depth of their lots to provide quite a bit of space inside. They are common in Pittsburgh because they were a good solution to the problem of cheap housing: they gave working families a reasonably sized house of their own that they could afford.

Old Pa Pitt would like to tell you that he climbed a tree in the howling wind just to get these pictures for you, but he would be pulling your leg. They were taken from the walkway of the Fallowfield streetcar viaduct.

If architecture is frozen music, then utility cables are the surface noise on a worn shellac record.

This duplex in Beechview is one of a pair right beside the Westfield stop on the Red Line. It looked very familiar. Where had we seen it before?

This duplex is on Ellsworth Avenue in Shadyside, part of a group of duplexes on St. James Place and the adjacent side of Ellsworth Avenue. It is not identical to the one in Beechview, but so many of their parts are identical that the Beechview and Shadyside duplexes were obviously drawn by the same pen.

Above, a perspective view of one of the pair in Beechview, which is marked “Woodside Dwellings” on a 1923 map. It stands on Westfield Street, which was briefly called Woodside Avenue; the other of the pair was called “Suburban Dwellings” after the cross street, Suburban Avenue. Except for the loss of the Tudor half-timbering in the front gable, this one is very well preserved. (Suburban Dwellings has lost more details.)

Below, a perspective view of one of the duplexes in Shadyside.

One of the details they share is a “No Outlet” sign. But we can see that the Shadyside duplexes are narrower and deeper than the Beechview ones. The same architect adapted as much of the same design as possible to the different dimensions of different lots.

Four more of these duplexes stand on St. James Place, a little one-block side street running back to the cliff overlooking the railroad and busway.

This one has kept its original tile roof.

A detail preserved by the one in Beechview is the Art Nouveau art glass with Jugendstil tulips.

Old Pa Pitt does not yet know the architect of these Tudor duplexes. But if he had to make a wild guess, he would guess Charles Bier. The wide arches with strong verticals above, and the filtering of Tudor detailing through a German-art-magazine Art Nouveau sensibility, strongly remind us of Bier’s other works. There are other known works of Bier both in Shadyside and in the South Hills.

In Shadyside, these Tudor duplexes are interspersed with Spanish Mission duplexes, showing once again that Tudor and Spanish Mission belong together.

This modest house in Beechview does not stand out a great deal from its neighbors. Its lines seem to be a little more simple, perhaps, but you would not stop to gawk at it when you walked by on the street.

The architect, however, was headed in an interesting direction. H. C. Clepper designed this house for Robert E. Sickenberger in 1914,1 and he was already flirting with the simplicity of modern style.2 Two decades later, Clepper (working for a bigger architectural firm) would be the designer of almost all the ultramodern concrete houses in Swan Acres, “America’s first modern suburb,” most of which still stand today and are still the objects of pilgrimages by architectural historians.

As we have seen many times before, surprisingly interesting bits of architectural history are ready to ambush us from the blandest streets once we know to look for them.

The current St. Catherine of Siena Church, today part of St. Teresa of Kolkata parish, inhabits a big warehouse-like building from the 1960s on Broadway in Beechview. But St. Catherine’s parish predates Beechview itself. It was originally in the heart of the village of Banksville, where it inhabited this frame building that still stands today, after many subsequent adventures.

City planning maps like to draw neighborhood boundaries down the middle of major streets. This often leads to absurd divisions where the spine street of a neighborhood is marked as the neighborhood boundary, putting half the neighborhood in a different neighborhood—as in Garfield and Arlington, for example. Banksville is another example: the neighborhood boundary goes right through the center of the old town of Banksville, putting the eastern half of it in Beechview, including this church. But when it was built, this church was in the heart of Banksville, right across Bank Street (later Gorn Avenue and now the driveway for this building) from the Banksville post office, the site of which is also in Beechview according to city planning maps.