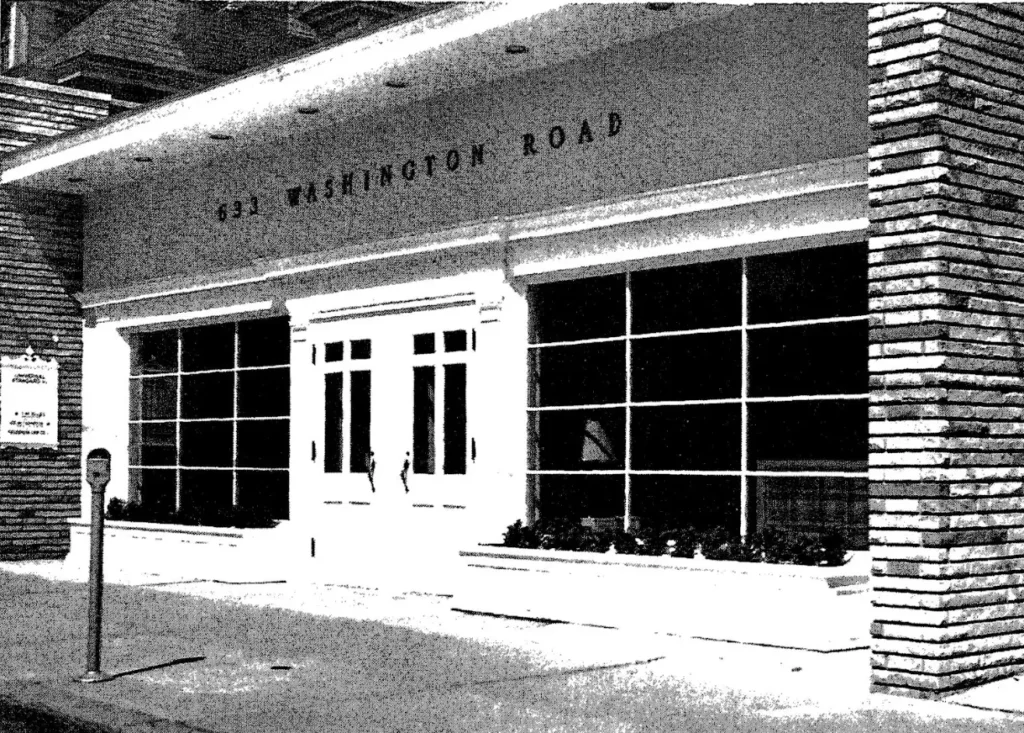

This is a building you walk right past without even noticing it. One of old Pa Pitt’s favorite things to do is to show people how interesting the things they walk right past can be. This building was the subject of an article in the Charette,(1) the magazine of the Pittsburgh Architectural Club, so we know quite a bit about it, including that it looked like this when it was just finished in 1952:

The architect was Vincent Schoeneman, known as “Shooey,” who had a flourishing practice in the middle of the twentieth century. He was “given carte blanche” on the design, the article tells us, but put some effort into making the building fit with its prewar neighbors. Thus the curious combination of modernist and Colonial elements.

Some things have changed. The windows have been replaced, trading the twelve horizontal panes on each side for three vertical sheets of glass, which is not an improvement. The signboard that once displayed the address in letters that managed to be both modest and large has been covered with aluminum (with a dark stripe that would be perfect for the words “633 WASHINGTON ROAD” spelled out in white letters). The wooden planters are no longer there, but they have been replaced by stone benches or shelves that match the side walls. The Colonial doors have been replaced with more ordinary stock doors. Still, a good bit of the original detail remains.

Cameras: Kodak EasyShare Z981; Nikon COOLPIX P100.

The whole text of the Charette article follows, reproduced here under the assumption that the copyright was not renewed.

Suburban Office Building

Vincent J. Schoeneman, Architect

G. Reed Agnew, General Contractor

Pittsburgh Architect Vincent J. Schoeneman, recently finding himself in the enviable position of being given carte blanche with regard to the design of a small office building in Mount Lebanon, Pittsburgh, made the unhappy discovery that he was unable to take full advantage of his unwonted freedom. The district itself imposed the limitations and virtually dictated the design.

In the mushrooming Mount Lebanon district where the growth has been haphazard and unplanned, churches, schools, office buildings and residences of every age and design rub shoulders. Against this mongrel background, architecturally speaking, Architect Schoeneman studiously avoided the path of least resistance by refusing to draw Greek Revival, Colonial or English Manor from the grab-bag of surrounding designs. Disregarding a completely contemporary approach in the interests of achieving some degree of harmony with neighboring structures, the architect came up with a fresh, satisfying design whose rough stone and flat roof stamp it unmistakedly Circa 1952 but whose white wood detail around the door and windows and ornamental columns give it a distinctly Colonial touch.

Fronting the main street on a 60′ x 140′ lot, the structure seems almost to be suspended from the two side walls, which thrust forward dramatically beyond the actual building line and reach three feet above the roof. These walls, of stone toward the street and cement block to the rear, serve the dual purpose of providing in the rough red stone, a strong textural and color contrast with the painted white pine of the door and window surrounds, and giving an illusion of size and height to a small proportioned building (39′ 10″ frontage, 66′ to the rear).

Large plate glass windows, intersected by white pine, admit maximum light to the hall and reception area and give an uninhibited view of a tastefully furnished, plaid-papered interior to passers-by. White flower boxes (painted pine) run beneath each window, the rich hues of the blossoms providing a bright stab of color against the stark white of the pine trim. A jutting 3′ roof overhang, housing the permaflector flood lighting equipment, wards off unwanted bright sunlight and introduces a strong horizontal plane to balance the vertical projection of the side walls.

The layout of the office building was determined by the client’s wish to confine occupancy of the offices to medical practitioners. Flanking a central corridor is a neat, compact arrangement of rooms—five on each side with a small foyer just inside the doorway. All rooms, while having separate entrances from the corridor, have been given connecting doors, in the event that a tenant might require more than one office—or all five—as a suite. Mindful of strict budget limitations, the offices represent the result of a careful study of special requirements and materials. Faced with the necessity of furnishing special plumbing and electrical wiring, Architect Schoeneman pared costs to the bone by his economical use of materials—simple plastered walls, asphalt tile flooring over ½″ plywood, acousti-fibre tile board ceiling and wood sash windows.

Another economy move was the elimination of a complete basement. Toilet rooms and a furnace room (oil-fired furnace) occupy the rear of the basement area, the rest being given over to crawl space of sufficient height to permit installation of an air-conditioned system.

Recognizing the need for parking facilities and quick and easy entrance and exit for the tenants, Mr. Schoeneman deemed it essential to include a parking lot on a 35′ excavation at the rear, entered directly from a side street; and a separate back entrance to the building itself.

Of wall bearing construction with wood joist, the structure was originally planned to be of steel beam, before NPA raised its ugly head and dictated the switch.

Leave a Reply