The Hunting-Davis Company was a versatile firm, but its specialty was industrial architecture. The McKinney Manufacturing Company warehouse was noted as an innovation in reinforced-concrete construction when it went up in 1914, and it still stands in very close to its original form, giving us a good look at the ultra-modern industrial architecture of the early twentieth century. We note that even such a utilitarian structure as a warehouse was not allowed to go up without some elegant Art Nouveau ornamentation:

Here is the architects’ Liverpool Street elevation as it appeared in an article in the Construction Record for February 7, 1914:

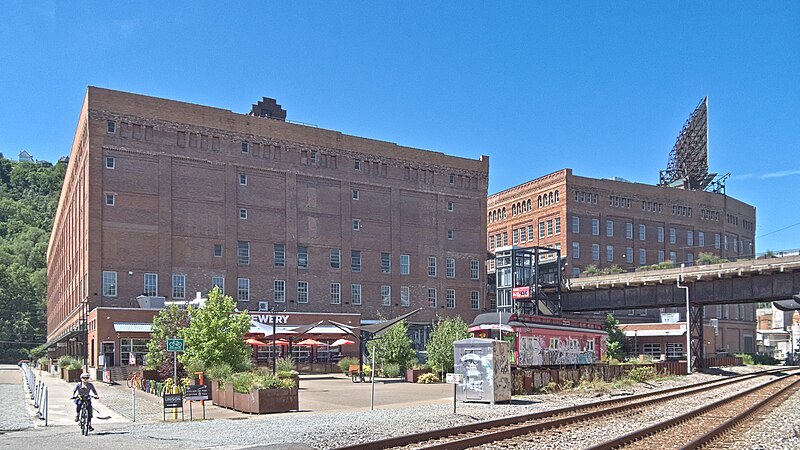

And here is the same building today:

This is the Preble Avenue side, which is shorter by one bay but otherwise similar. Old Pa Pitt would have preferred to duplicate the architects’ drawing as closely as possible, but Liverpool Street no longer exists in that block: it has been filled in with lower buildings.

Here is the text of the article, which will be of interest to students of architecture and construction:

Last week the contract for building the warehouse for the McKinney Manufacturing Company, Northside, Pittsburgh, was placed with the Henry Shenk Company, Pittsburgh. The building as designed by the Hunting-Davis Company, Century building, Pittsburgh, will be approximately 105×120 feet, six stories high with basement. It will be of reinforced concrete throughout. There will be no steel beams or girders used in the construction work except those for the outside lintels and elevator framing.

In order that the reinforced concrete work may be properly constructed, thus eliminating any possibility of poor workmanship and accidents, it is agreed that superintendent of five years experience on reinforced concrete building must remain on the work at all times. The mixture of the concrete will be one part cement, two parts sand and four parts gravel. All columns will have a one to two cement and sand mortar placed to a depth of three inches before the concrete is placed. The columns will be cast a day ahead of the beams and slabs. Care is to be exercised in removing the forms so that no board marks or imperfections on the exterior of the building are noticeable.

The building will be one of the heaviest loaded flat slab buildings ever designed in the country. A four-way diagonal reinforcement will be used in the slab construction. The columns will have hoop-reinforced concrete. All ceilings will be flat. The floor loads per square foot will be as follows: First floor, 800 pounds; second floor, 1,200 pounds; third floor, 650 pounds; fourth floor, 450 pounds; fifth and sixth floors, 300 pounds. The basement floor and walls will be reinforced to take care of flood water pressure with flood gates on basement windows.

The design carries with the proposed work the building of a tunnel to connect with the present plant and the construction of a bridge to connect up with the second floor. Solid steel sash will be used on all windows. A sprinkler system will be installed. All floors in the basement tunnel and pent houses will have a granolithic finish.

For the connecting bridge the walls and roof will be constructed of self-centering material plastered with cement mortar. The walls will be two inches thick and finished smooth on both sides. The roof will be two and one-half inches thick and finished with a smooth under coat. Composition roofing will be used throughout all the work.