This building was put up in two stages. It was built in 1902 as a seven-story building; two years later six more floors were added. Originally it had a cornice and a Renaissance-style parapet at the top, without which it looks a little unfinished.

From The Builder, April 1904. The architect, as we see in the caption, was James T. Steen, who had a thriving practice designing all sorts of buildings, including many prominent commercial blocks downtown. This was probably his largest project.

At first glance this looks like a postmodernist building from the 1980s, and your first instinct is half right. It was originally an early ten-storey skyscraper built for the Shields Rubber Company in 1903. In 1989, it got a heavy postmodern makeover, with an extra floor at the top.

These views are made possible by the demolition of the buildings along the east side of Market Street.

Cameras: Kodak EasyShare Z1285; Fujifilm FinePix Hs10.

Left to right: the Benedum-Trees Building (built 1905 as the Machesney Building, architect Thomas Scott); the Investment Building (1927, John M. Donn); and the Arrott Building (1902, Frederick Osterling).

At the corner of Seventh Avenue and William Penn Place is a complicated and confused nest of buildings that belonged to the Bell Telephone Company. They are the product of a series of constructions and expansions supervised by different architects. This is the biggest of the lot, currently the 25th-tallest skyscraper in Pittsburgh, counting the nearly completed FNB Financial Center in the list.

The group started with the original Telephone Building, designed by Frederick Osterling in Romanesque style. Behind that, and now visible only from a tiny narrow alley, is an addition, probably larger than the original building, designed by Alden & Harlow. Last came this building, which wraps around the other two in an L shape; it was built in 1923 and designed by James T. Windrim, Bell of Pennsylvania’s court architect at the time, and the probable designer of all those Renaissance-palace telephone exchanges you see in city neighborhoods. The style is straightforward classicism that looks back to the Beaux Arts skyscrapers of the previous generation and forward to the streamlined towers that would soon sprout nearby.

Hidden from most people’s view is a charming arcade along Strawberry Way behind the building.

The local firm of Burt Hill Kosar Rittelman designed the second-most-important Postmodernist development in Pittsburgh, after PPG Place. This one does not get the attention lavished on Philip Johnson’s forest of glass-Gothic pinnacles: it never gets to play a supervillain’s headquarters in the movies, and it is seldom pointed out as one of Pittsburgh’s top sights. But to old Pa Pitt’s eye it is a particularly pleasing manifestation of what was called Postmodernism at the time, but might be more accurately termed the Art Deco Revival. It consists of two skyscrapers—currently known as the Federated Hermes Tower and the Westin Convention Center Pittsburgh—linked by lower sections of building that fill in the rest of the block.

Seen from Mount Washington. We also have some pictures from Gateway Center Park (with a little more about the building), and from the Boulevard of the Allies.

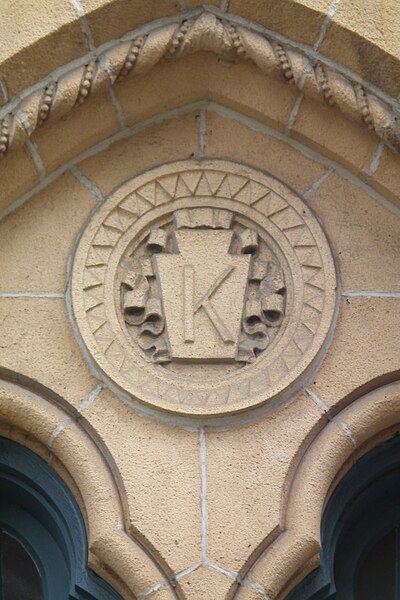

The Keystone Athletic Club was designed by Benno Janssen, Pittsburgh’s favorite architect for high-class clubs of all sorts. Most of them were classical in style, but for this skyscraper clubhouse Janssen chose a simple and streamlined Gothic style instead. It is now Lawrence Hall, the main building of Point Park University, so that two universities in Pittsburgh have trademark Gothic skyscrapers.

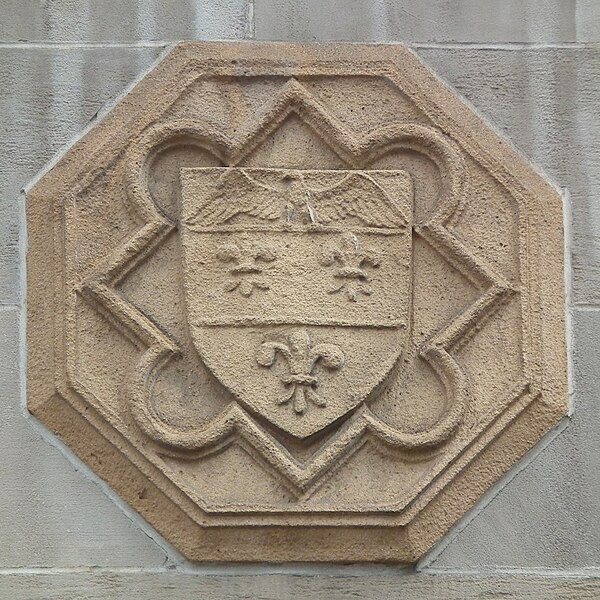

Early in his career, Benno Janssen was a fiend for terra cotta; he was much more restrained later on, but he usually included some characteristically appropriate terra-cotta ornaments.