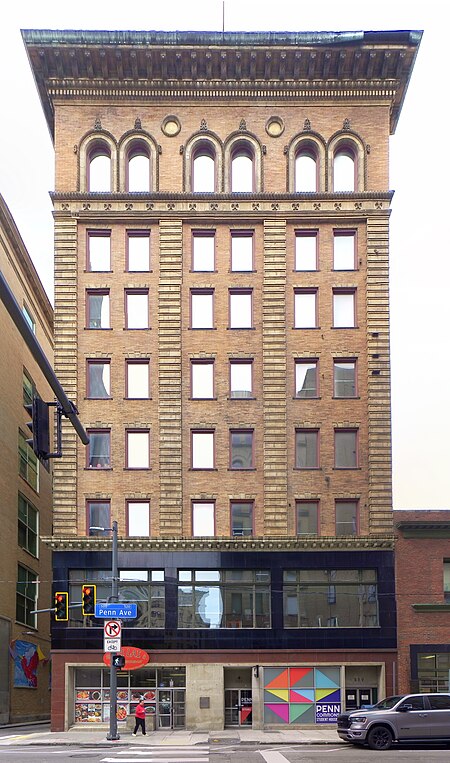

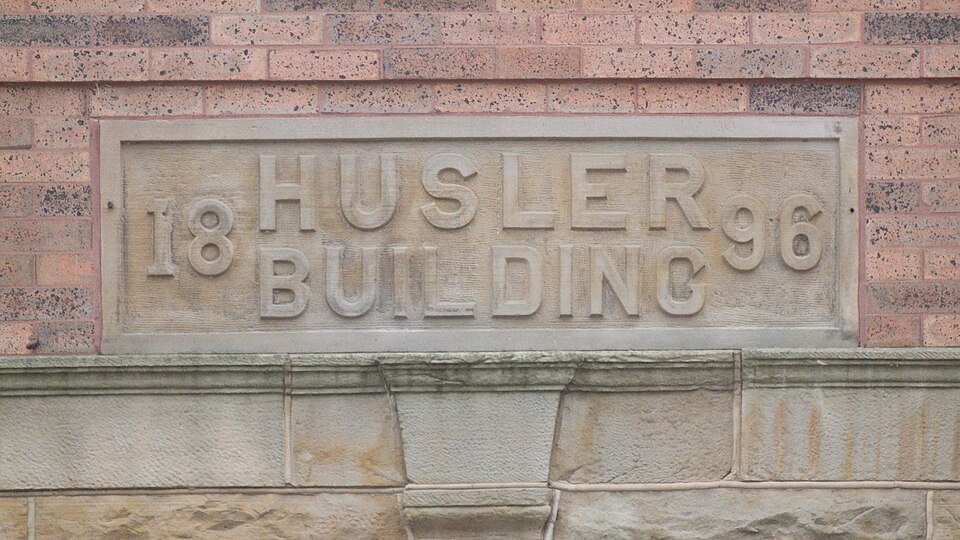

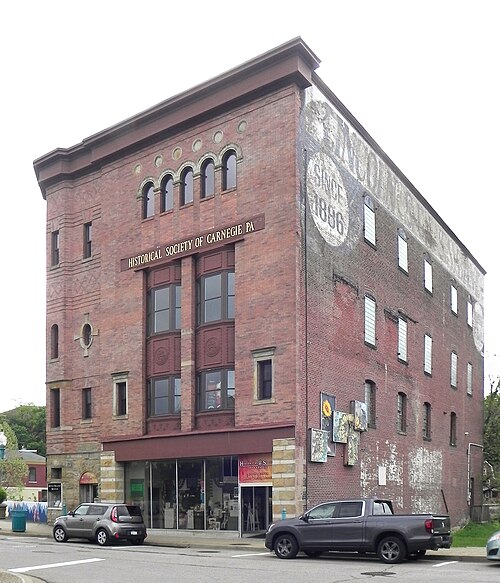

Samuel T. McClarren, a very successful Victorian architect and a resident of nearby Thornburg, designed this landmark building, which was put up in 1896.

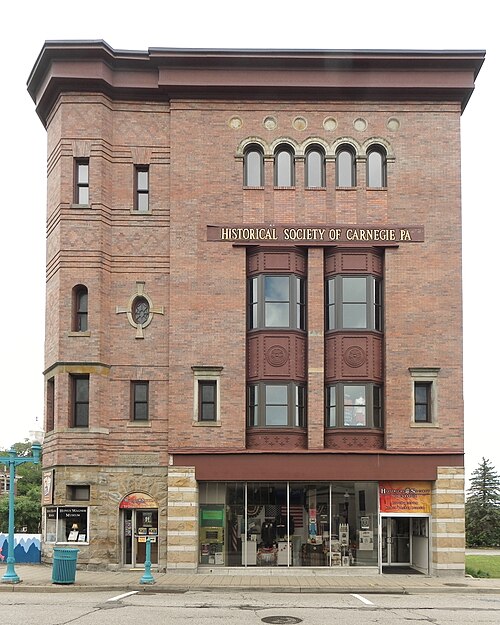

A small alteration to the front gives us an example of how important the little details are to the appearance of a building. The arched windows in the top floor have been shortened, as we can see by the slightly different shade of brick where they have been filled in. The original design would have created a single broad stripe from the arches at the top to the storefront below. Interrupting that composition makes the building look awkward and top-heavy. The ground floor has also been altered in a way that obscures the vigor of the design. Once we have said that, however, we should acknowledge that the building is generally in a good state of preservation and praise the Historical Society of Carnegie for keeping it up.

This building has a very difficult lot to deal with, and the architect must have found it an interesting challenge. First, the lot is a triangle. A kind of turret blunts the odd angle on the Main Street end and turns it from a bug into a feature.

The second challenge is that one long side of the lot is smack up against Chartiers Creek, a minor river that is placid most of the time but can be a raging torrent when storms make it angry. The foundations would have had to take all the moods of the river into account, and the fact that the building has stood through disastrous floods suggests that Mr. McClarren knew what he was up to.

A view from across Chartiers Creek shows us the sharp point of the triangle in the rear.

Comments