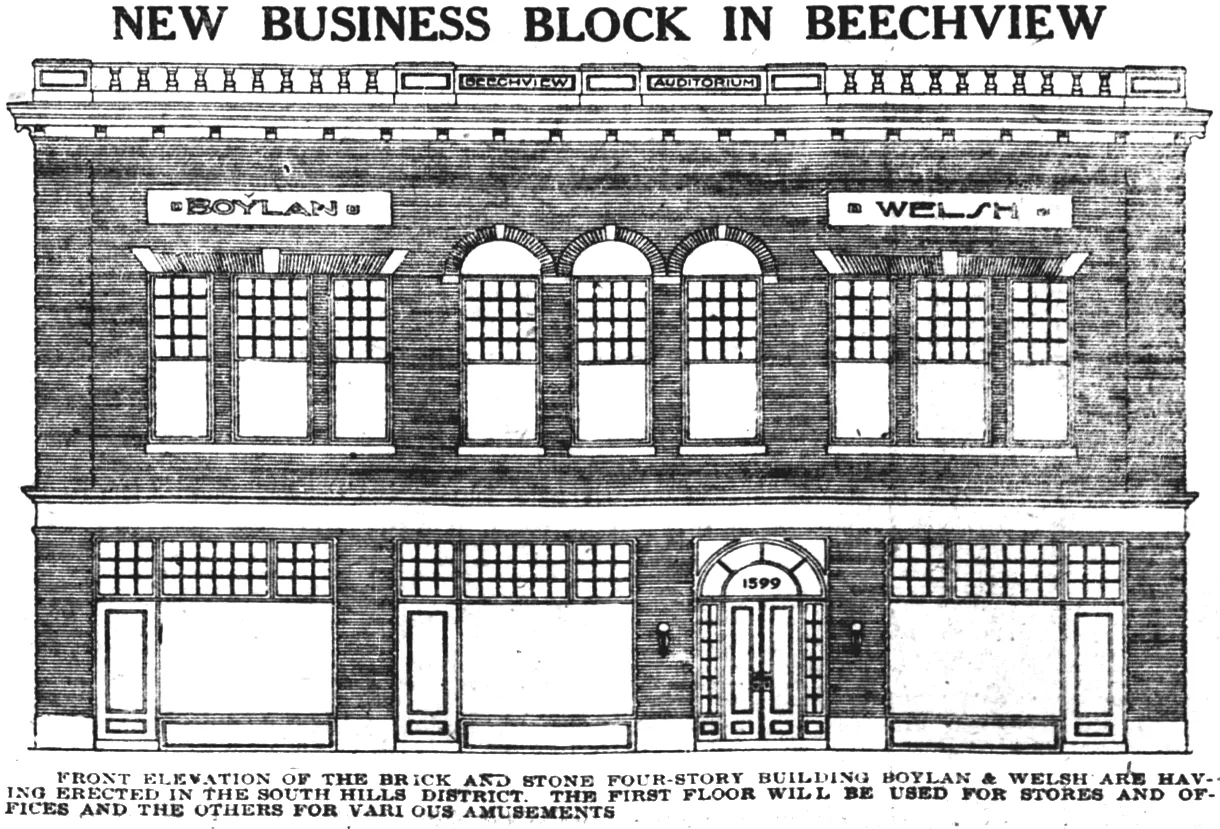

Here is a drawing of Rowe’s department store that was published in 1907, when East Liberty was booming as it became the business hub for rapidly developing East End neighborhoods. The building, put up in 1898, still looks much the same today, though it has been many years since it housed a department store. By choosing Alden & Harlow, the most prestigious firm in the city, as his architects, Mr. Rowe declared to East End residents that he would offer them as high a class of merchandise as they could find anywhere downtown.

The drawing came from a lavishly illustrated book published in 1907 by the Pittsburg Board of Trade—a book that, oddly, has two titles: Up-Town: Greater Pittsburg’s Classic Section/East End: The World’s Most Beautiful Suburb. Here is what the book tells us about Rowe’s:

C. H. ROWE CO.

To the residents of the East End the department store of C. H. Rowe Company, at Penn and Highland avenues, is a household word. Little can be said of it which every woman and child does not already know, yet no history of the development of the East End would be complete without mention of this enterprising company.

It was in 1898 that C. H. Rowe Co. began to relieve the residents of the East End of the necessity of going down town to meet any requirements they had in the matter of dress goods, undermuslins, white goods of every description, millinery, children’s outfittings, all that the feminine domestic economy required.

Such enterprise as the firm of C. H. Rowe Co. has shown has naturally received a hearty response from the residents of the East End. The aim of this section of the city is to provide every want that its citizens require. So far as the dry goods business is concerned that is what this company has done.

It takes a modern four-story establishment, with 58,000 square feet of floor space to accommodate the company’s stock of goods. It requires 125 persons in the dullest season to attend the wants of the customers of C. H. Rowe Company and many delivery wagons are employed in distributing the goods to such customers who prefer that accommodation.

The directors of the company include Messrs. C. H. and W. H. Rowe, D. P. Black, H. P. Pears and J. H. McCrady. James S. Mackie is the general manager.

It is little wonder with such attention to all the requirements of the East End public that C. H. Rowe Company’s store has become the veritable center of the East End trade, and that its growth is so much a matter of pride not only to the members of the firm but to the residents of the entire East Liberty community.

More pictures of the Rowe’s or Penn-Highland Building.

Comments