Here is another church with the sanctuary upstairs, if you look at the front. This is Pittsburgh, though, so upstairs is the ground floor in the rear.

Comments

Here is another church with the sanctuary upstairs, if you look at the front. This is Pittsburgh, though, so upstairs is the ground floor in the rear.

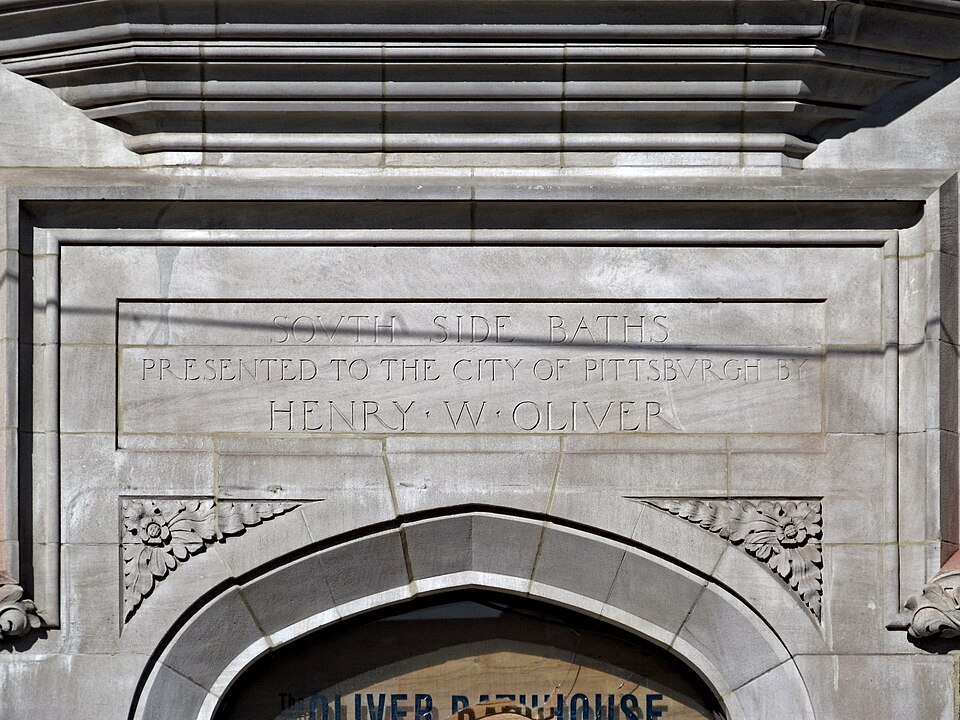

The Oliver Bathhouse, built as the South Side Baths but soon renamed for its donor (who had died in the long delay between the donation and the construction), has been getting a thorough restoration and renovation. The outside of the building looks almost brand new.

This picture from Preservation Pittsburgh’s collection is dated January 31, 1913, at Wikimedia Commons, but that is an error. In the Construction Record for May 30, 1914, we read, “Architects MacClure & Spahr, Keystone building, will lake bids until June 1 on the erection of a brick, stone and terra cotta fireproof bath house on Tenth and Bingham streets, for the Henry W. Oliver Estate. Cost $100,000.” The building might have been finished by January of 1915 if the construction got started right away. Wikipedia concurs that the building was finished in 1915. Since this picture was taken from a printed source, we suspect that a poorly-scanned “1918” might have been misread as “1913.”

Oliver’s steel mills nearby employed many of the workmen who would benefit from these baths. He might not pay them enough to afford more than squalid tenements with inadequate bathing facilities, but he was willing to spend enough to make them smell better on Saturday nights.

The Oliver Bathhouse survives as a bathhouse, uniquely among the public baths in Pittsburgh, because the more upscale denizens of today’s South Side appreciate its large indoor swimming pool, the only city pool open in the winter.

More pictures of the Oliver Bathhouse.

Map.

Rutan & Russell, both of whom had worked for H. H. Richardson, designed this immense Jacobean pile for steel baron Benjamin Franklin Jones, Jr., son of the Jones of Jones & Laughlin. It was finished in 1910. The terra-cotta company must have made its numbers for the entire year supplying the ornaments for this house, right down to the address over the entrance.

The house now belongs to the Community College of Allegheny County, which keeps the exterior perfect.

Even the downspouts are works of art.

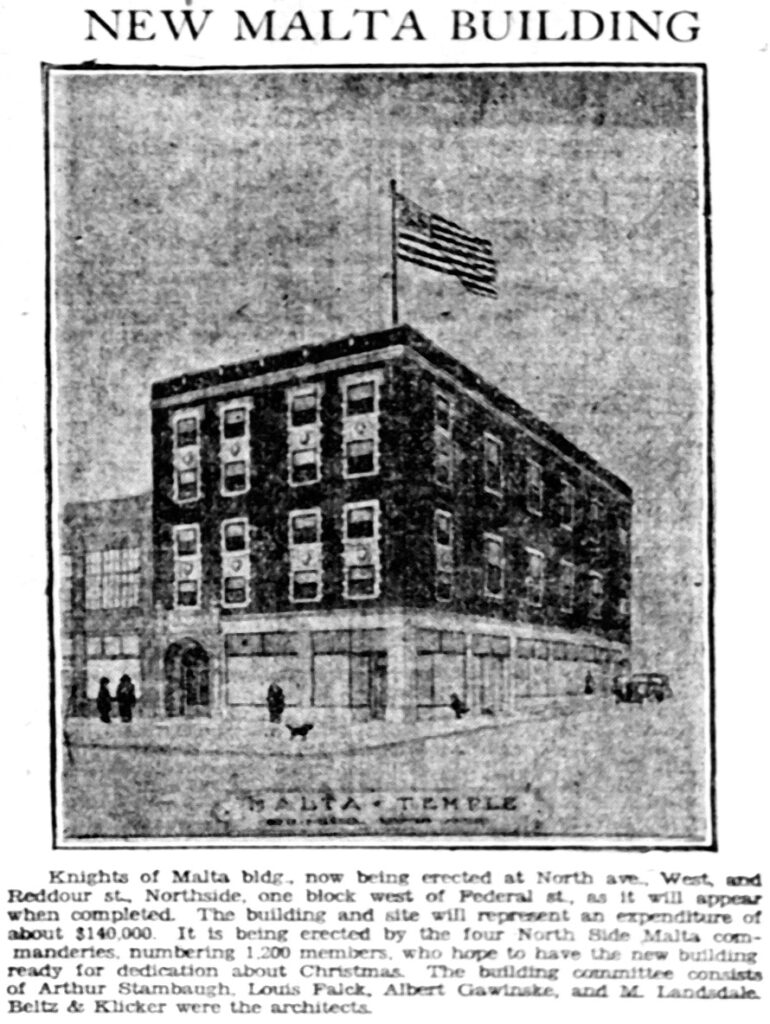

Built in 1927, this was a lodge for the Knights of Malta, one of those Masonic orders that old Pa Pitt has never sorted out. Most North Siders remember it as the Salvation Army building. It narrowly escaped demolition in 2008, and now it is in good shape again and ready for its next life.

Addendum: The architects were Beltz & Klicker, as we learn from their own drawing of the building as it was published in the Press on September 11, 1927.

“Knights of Malta bldg., now being erected at North ave. West, and Reddour st., Northside, one block west of Federal st., as it will appear when completed. The building and site will represent an expenditure of about $140,000. It is being erected by the four North Side Malta commanderies, numbering 1,200 members, who hope to have the new building ready for dedication about Christmas. The building committee consists of Arthur Stambaugh, Louis Falck, Albert Gawinske, and M. Landsdale. Beltz & Klicker were the architects.”

Still in use, with modern additions, as Crafton Elementary School, this Jacobean palace was built in 1913. The architect was Press C. Dowler, already well into a career that would last another half-century. His assignment here seems to have been to make up in spectacle for what the little borough’s high school lacked in size, and he came through with the goods, festooning the building with crenellations and terra-cotta ornamentation. But although the decoration may be a bit extravagant, it is done with good taste, making a balanced composition outlined by the sharp contrast between the red brick and the white trim.

The original school had two identical entrances—probably, as was common in those days, one for boys and one for girls.

Designed by Washington (D. C.) architect Philip Morison Jullien, the Fairfax was one of the grandest apartment houses in Pittsburgh when it opened in 1927. It certainly isn’t our biggest apartment building now, but it still makes a strong impression as you walk past on Fifth Avenue.

The school for Neville Township, the municipality whose borders are the shores of Neville Island, was built in three main stages. The little school above, with four or five rooms, was the first.

Some time later, a two-storey building in a matching Jacobean style was built around the corner. (Addendum: Father Pitt has some reason to believe, but no definite proof yet, that the architect of both the prewar school buildings was John H. Phillips of McKees Rocks, who designed many schools for suburban boroughs.)

Finally, a postwar modern section was added, probably around 1960 to judge from the style. It was not in use for a long time: old Pa Pitt had a very pleasant conversation with a neighborhood resident whose wife was a member of the last graduating class of this school in 1971. Neville Township and Coraopolis merged their school systems into the Cornell School District, whose name is a portmanteau of the two municipalities. Fortunately, the buildings have found other uses.

Two grand Presbyterian churches stand at the two ends of Uptown Mount Lebanon. But they are different kinds of Presbyterians. The one to the north was the United Presbyterian church, but it has now become Evangelical Presbyterian. This one is now Presbyterian Church (USA).

“In these days of mergers,” James Macqueen (himself one of our notable architects) wrote in the Charette in 1930, “one wonders why theological differences stood in the way of unity, and that these Presbyterians did not build one great building in this community instead of two with their attendant extra overhead involved. However, both of these two churches are worthy of a visit, as they show the great advance that has been made in Church work during the past few years…”

Southminster was designed by Thomas Pringle and built in 1928.

These quatrefoil ornaments at the top of the tower can be properly appreciated with a very long lens.

The office and education wing is done in a complementary Jacobean style. The arcade makes both a visual and a practical link to the main church.

Appropriately for a building dedicated to Christian education, the Reformation slogan VDMA—Verbum Domini Manet in Aeternum (“The word of God endureth for ever,” 1 Peter 1:25)—is engraved in an open book.

We have more pictures of Southminster Presbyterian from a couple of years ago.

We have seen the Berkshire before, but those pictures weren’t very good, so old Pa Pitt went back and got better ones. It’s a courtyard apartment building in the Mount Lebanon Historic District; as Father Pitt said the first time he visited, this building is in a simple but attractive Jacobean style, where a few effective details carry all the thematic weight.

An elegant Tudor or Jacobean mansion designed by MacClure & Spahr and built in 1903, as the dormer tells us. This Post-Gazette story (reprinted in a Greenville, North Carolina, paper that does not keep it behind a paywall) tells us that a 1925 addition was designed by Benno Janssen, who had worked in the MacClure & Spahr office and may have had some responsibility for the original design. The article also tells us how vandals masquerading as interior designers rampaged through the house and painted all the interior woodwork white or pale grey to “banish dark wood,” but at least the exterior is in good shape.