A few details of the Union Trust Building, designed by Pierre A. Liesch when he was working for Frederick Osterling—at least according to Liesch; the building is usually just credited to Osterling.

Comments

A few details of the Union Trust Building, designed by Pierre A. Liesch when he was working for Frederick Osterling—at least according to Liesch; the building is usually just credited to Osterling.

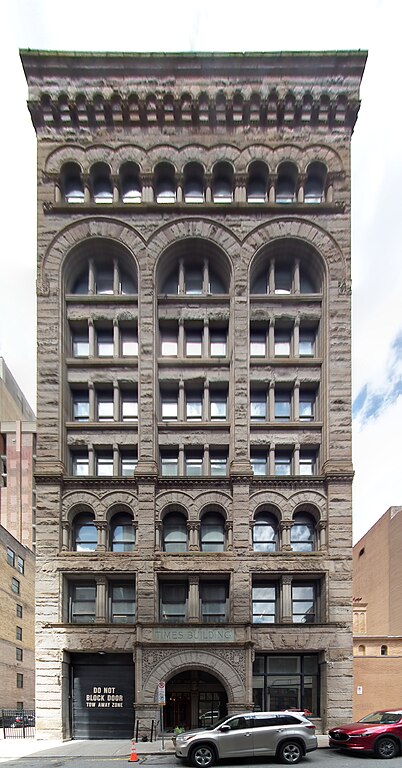

This building stands out among the skyscrapers that surround it like a strange relic of a lost civilization—the pre-skyscraper age. It was built in 1890, and the architect was young Frederick Osterling. He would soon master the Richardsonian Romanesque style and become one of our most accomplished practitioners of it, but this is pre-Richardsonian Romanesque. The weighty but graceful eyebrows over the arches, the complex and irregular rhythm of different sizes, and the surprising but flowing curves all remind us of Osterling’s old master Joseph Stillburg, whose Romanesque ideas went back to his native Austria.

Urban legend says that these structures are chapels where the privileged can repent of their sins, but in fact they house the elevator mechanics and other rooftop necessities.

Built in 1890, this rich feast of stonework was designed by Frederick Osterling in his Richardsonian Romanesque phase.

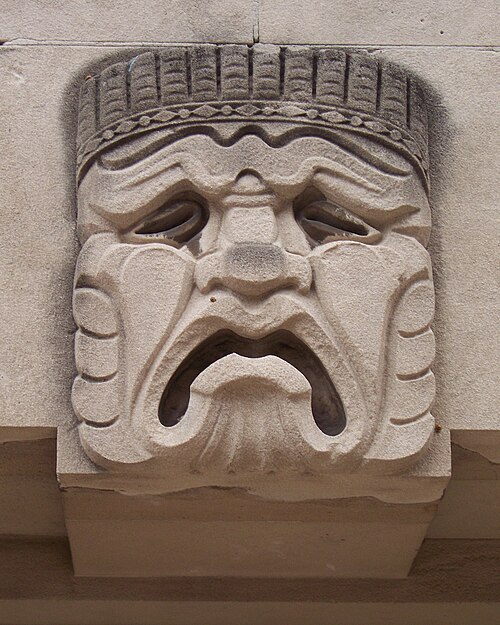

The carved ornaments are by Achille Giammartini, including old Pa Pitt’s favorite gargoyle in the city.

Allegheny High School, now the Allegheny Traditional Academy, has a complicated architectural history involving two notable architects at three very different times.

The original 1893 Allegheny High School on this site was designed by Frederick Osterling in his most florid Richardsonian Romanesque manner. This building no longer exists, but the photograph above gives us a good notion of the impression it made. The huge entrance arch is particularly striking, and particularly Osterling; compare it with the Third Avenue entrance of the Times Building, also by Osterling.

In 1904, the school needed a major addition. Again Osterling was called on, but by this time Richardsonian Romanesque had passed out of fashion, and Osterling’s own tastes had changed. The Allegheny High School Annex still stands, and Osterling pulled off a remarkable feat: he made a building in modified Georgian style that matched current classical tastes while still being a good fit with, and echoing the lines of, the original Romanesque school.

The carved ornaments on the original school were executed by Achille Giammartini, and we would guess that he was brought back for the work on the Annex as well.

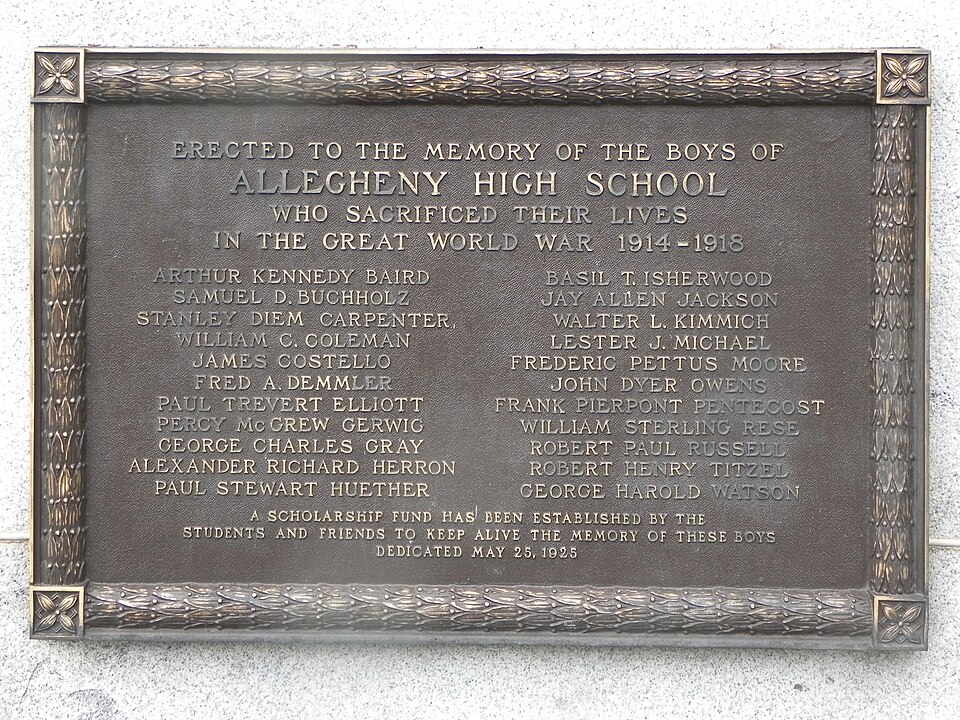

A war memorial on the front of the Annex. Twenty-two names are inscribed. Everyone who went to Allegheny High in those years knew someone who was killed in the Great War.

By the 1930s, the school was too small again. The original school was torn down, and Marion Steen, house architect for Pittsburgh Public Schools (and son of the Pittsburgh titan James T. Steen) designed a new Art Deco palace nothing like the remaining Annex. The two buildings do not clash, however, because there are very few vantage points from which we can see both at once.

The auditorium has three exits, each one with one of the three traditional masks of Greek drama above it: Comedy, Meh, and Tragedy.

A minor work of a major architect, this building on Shiloh Street has suffered multiple renovations since it was built in 1911 that have gradually taken away much of its character. The ground floor was completely remodeled; the arched windows have been replaced with square windows and the arches filled in; and just a few years ago the roofline lost a crest. Still, what remains gives us some idea of how Frederick Osterling handled a small commission.

The Times Building, designed by Frederick Osterling in his Richardsonian Romanesque period, is a block deep, so it has fronts on both Fourth Avenue and Third Avenue. The Fourth Avenue front is narrower; the Third Avenue front has one more bay, and a single grand arch in the middle. The decorative carving is probably by Achille Giammartini, who is known to have worked with Osterling on the Marine Bank and the Bell Telephone Building, and all his trademark whimsy is on display here.

Thanks to the research of an architect correspondent, we can say with fair confidence that this neglected building on Smithfield Street was designed by Frederick Osterling, one of the titans of Pittsburgh architecture. It was built in about 1898 for John Daub, whose name in big letters stares down at us from above the fifth floor.1

This building has suffered the usual loss of cornice, and the first floor was entirely remodeled at some point by someone who thought weird pebbledash stucco would look just right on a Romanesque building from the 1890s. But between those extremities most of the decorative details are preserved.

The Daub Building is vacant right now and therefore in danger; we hope that its attribution to Osterling will encourage preservation and restoration.