The Skinny Building, possibly the world’s narrowest commercial building, has returned to its roots as a lunch counter.

Comments

The Skinny Building, possibly the world’s narrowest commercial building, has returned to its roots as a lunch counter.

A massive new apartment tower for Duquesne University students, and a big improvement in the Uptown cityscape (it replaced a parking lot). The architects were Indovina Associates, who designed the building in a subdued version of the currently popular patchwork-quilt style, with materials that harmonize well with the other buildings along the Uptown corridor.

S. S. Kresge was never the presence in Pittsburgh that Murphy’s was, but all the five-and-dime stores had outlets downtown. Murphy’s, Kresge’s, McCrory’s, Woolworth’s—they were all similar operations, and all the founders knew each other. G. C. Murphy, in fact, had worked for S. S. Kresge and John G. McCrory before setting out on his own.

The S. S. Kresge Company is better known to younger people (meaning under the age of seventy or so) as the parent corporation of Kmart.

The whole front of the building is done in terra cotta, including this inscription.

The pediment, though it seems undersized for the building, is filled with rich decoration.

The giant Kaufmann’s department store grew in stages over decades. This part of it was designed by Charles Bickel, who decorated it with exceptionally fine terra-cotta ornaments.

Stanley Roush, the county’s official architect, designed this building to hold the offices that were spilling out of the Courthouse and the City-County Building as Pittsburgh and its neighbors grew rapidly. It was built in 1929–1931, and it is an interesting stylistic bridge between eras. Roush’s taste was very much in the modernistic Art Deco line, but the Romanesque Allegheny County Courthouse, designed by the sainted Henry Hobson Richardson, was a looming presence that still dictated what Allegheny County thought of its own architectural style. Roush’s compromise is almost unique: Art Deco Romanesque. We have many buildings where classical details are given a Deco spin—a style that, when applied to public buildings, old Pa Pitt likes to call American Fascist. But here the details are streamlined versions of medieval Romanesque, right down to gargoyles on the corners. Above, the Ross Street side of the building; below, the Forbes Avenue side.

One of the entrances on Forbes Avenue.

Moses with the tablets of the Law. His beard obscures the Tenth Commandment, so go ahead and covet anything you like, except—if you are Lutheran—your neighbor’s house, or—if you are Catholic—your neighbor’s wife or house. Counting up to ten is harder than it looks when it comes to Commandments, and you may need to refer to Wikipedia’s handy chart to find how the numbering works in your religious tradition.

The bridge in this medallion looks a lot like the Tenth Street Bridge, which by pure coincidence was designed by Stanley Roush.

Decorative grate with an Allegheny County monogram.

Some very expensive columns, smooth and classically proportioned but with elaborate Deco Romanesque capitals.

We have more pictures of the decorations on the County Office Building, including those gargoyles we mentioned.

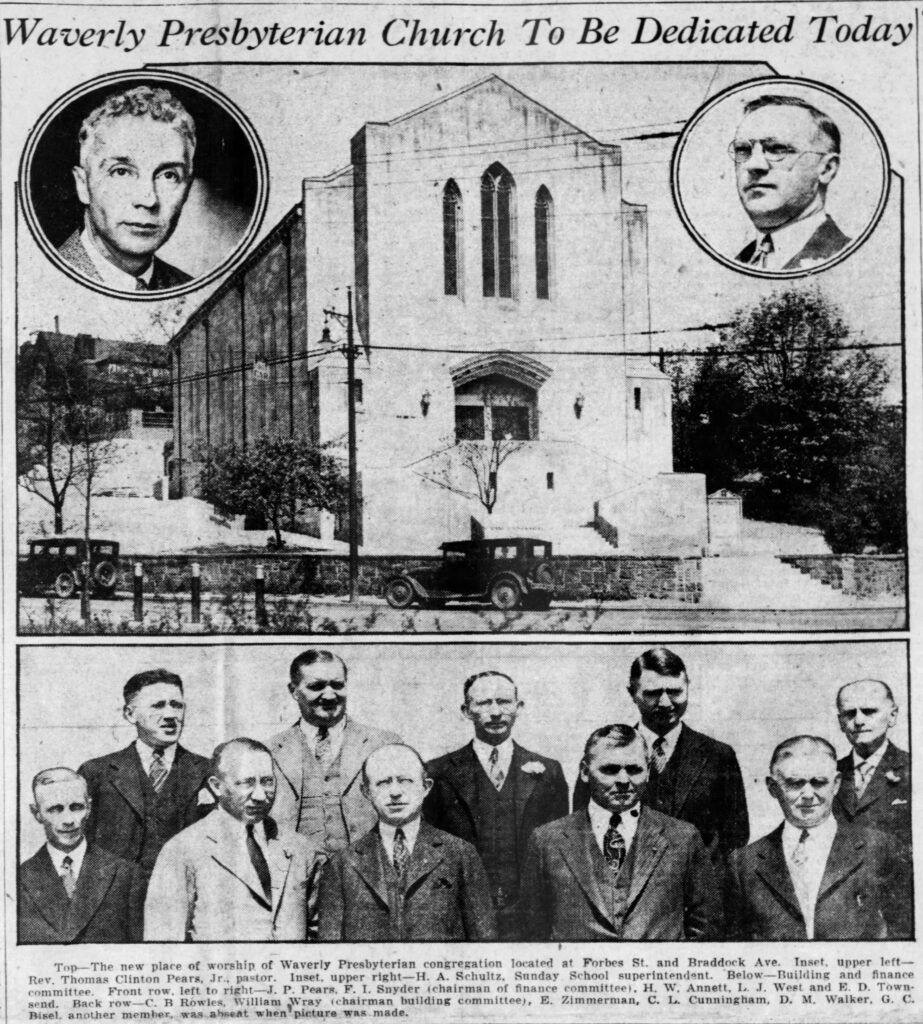

A magnificent building that takes full advantage of a magnificent site, right at the busy corner of Forbes and Braddock Avenues. It was dedicated in 1930; the architects were Ingham & Boyd, who abstracted the Gothic style into a cool and elegant modernism that does not look dated at all almost a century later.

When the cornerstone was laid on November 17, 1928, the Press described the planned facilities:

The new church will be of early English gothic style of architecture. The contract for the erection of the church has been awarded to Edward A. Wehr, noted builder of a number of famous churches in Pittsburgh and other cities. The seating capacity of the new edifice will be slightly in excess of 600. The exterior walls will be of Indiana limestone. The roof will be an “open timber” roof, with wood trusses exposed. In the vestibule, oak paneling will be used to the top of the doors, with plaster above and an oak beam ceiling. The floor of the vestibule will be tile. Paneled and carved woodwork will be used at the front of the auditorium, the pulpit, reading desk, choir gallery and organ screen being designed as a unit to create a focal point in the design at this location. Temporary windows will be of leaded glass of good quality, in the hope that from time to time these temporary windows may be replaced with memorial windows of stained glass, of high quality in design and workmanship.

That the assembly room on the ground floor may be used as a social room as well as for Sunday school purposes, a temporary kitchen has been arranged for, adjoining. At the opposite end of the assembly room, shower baths and locker rooms have been provided in accordance with the original intention of using this room for recreational purposes also.

—“Sunday Service to Mark Start on New Church,” Pittsburgh Press, November 17, 1928, p. 5.

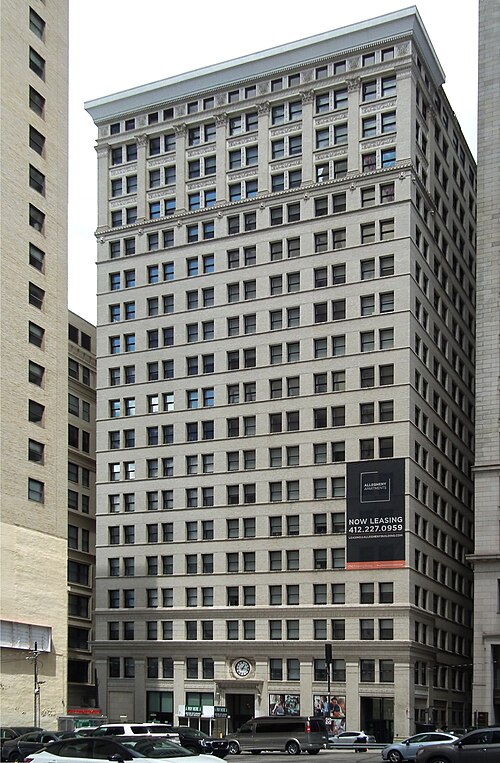

Built in 1906, this skyscraper was designed by Daniel Burnham, architect of the neighboring Frick Building, as the second part of Henry Frick’s architectural tantrum that cut off the light and air from the Carnegie Building. The Carnegie Building was demolished to make way for the nearly windowless Kaufmann’s Annex; this building, which gets plenty of light, is now luxury apartments.

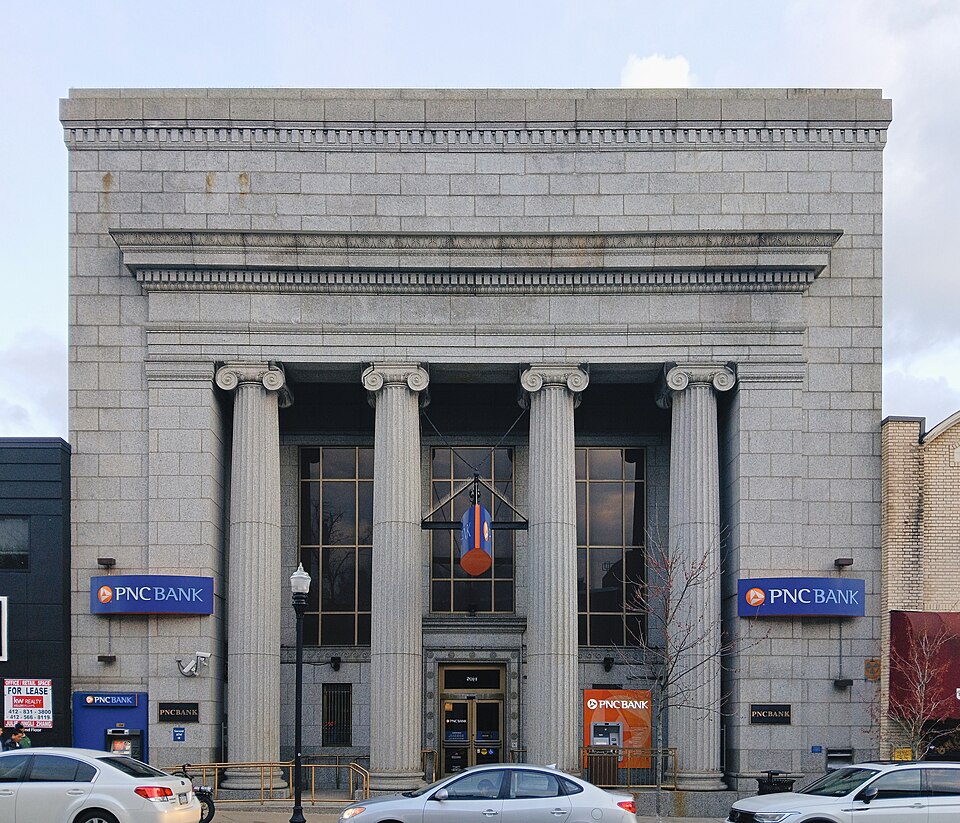

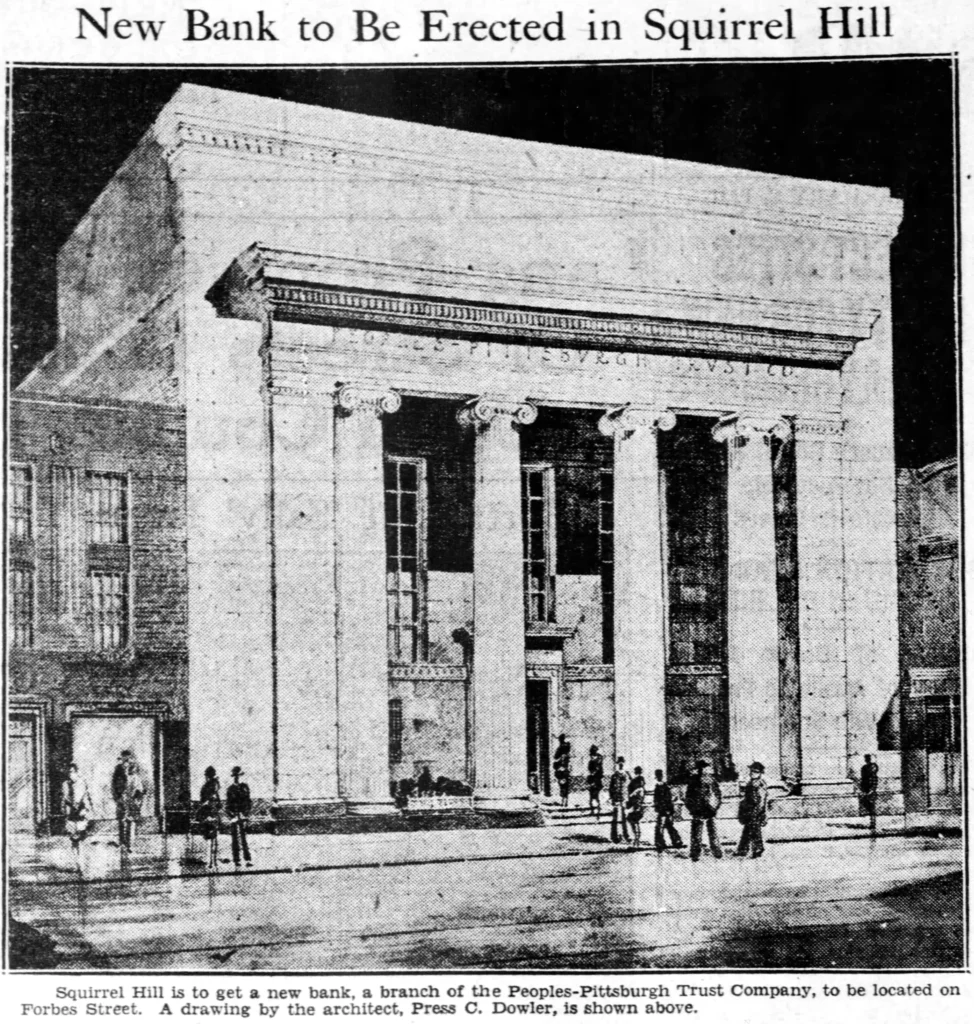

You could count on architect Press C. Dowler for the bankiest-looking banks. The correct Ionic front of this one looks almost exactly the way he drew it, as we can see from the architect’s rendering that was published in the Press on February 8, 1931.

It seems to old Pa Pitt that the mark of a Dowler bank is correct classical detail combined with a lack of fussiness. There is never too much detail. But he takes the details seriously. In other buildings he was already adopting Art Deco and modernist styles, but a bank needed to look traditional and timeless—especially in the Depression. For other Dowler bank designs, see the Coraopolis Savings and Trust Company and the Braddock National Bank.

This building at the corner of Forbes Avenue and Craig Street was designed by S. A. Hall in 1904.1 It still holds down its corner very well, and most of the original details are preserved—including the art-glass transoms.

This small Romanesque commercial building at the corner of Forbes Avenue and Marion Street, probably built in the late 1880s or the 1890s, has a stone front that makes it a little more elaborate than its neighbors. It probably had a couple of pinnacles along the roofline that would have made it stand out even more. It has been modernized a little, which obscures some of the original details, but it appears that it originally had a corner entrance, and weathered Romanesque carvings—including an almost-obliterated face peering out of the foliage—still adorn the capital of the thick column at the corner.

The building next door, which seems to have been built a few years later, was obviously meant to continue the stone front of the corner building, with similar stone and lintels and a similar broad arch.