An elegant little storefront designed by Alden & Harlow in 1908. It now houses a men’s clothing store.

This is a particularly grand rowhouse: note how much taller it is than its neighbor, indicating high ceilings. It seems to be abandoned right now, but perhaps it has a chance if the urban pioneers moving into the neighborhood get to it before it mysteriously catches fire. There is much worth preserving: the woodwork is in fairly good shape, and the windows—mostly unbroken—are still original and proper for the period. The location of the house on Fifth Avenue might make it attractive, but also might put it in the way if development mania reaches this part of the street.

This building was our first specialty eye and ear hospital, and a brief description from a history published in 1922 will show us how the idea of a hospital has changed in a century.

Located on Fifth avenue, corner of Jumonville street, is the Eye and Ear Hospital, under the auspices of a board of women managers. It had its inception at a meeting held May 20, 1895, at the home of Miss Sarah H. Killikelly, who during her lifetime was well known in the literary and historical circles of the city. A charter was secured June 22, 1895, and a location was secured on Penn avenue, but a removal was made to the present building in 1905. The first board of managers consisted of thirteen women and two physicians, eye specialists, for the medical and surgical treatment of all diseases of the eye, ear, nose and throat. The patients are divided into three classes—first, for the poor who require treatment of a character that is not necessary to detain them at the hospital; second, for the poor who require detention in the hospital, to whom free beds are allotted in the wards and a nominal charge made if they are able to pay; third, for those able to pay, private rooms are furnished, therefore the hospital is in no sense a charity; it must under its charter minister without charge to all those who suffer from any disease of the eye and ear, who are unable to pay for treatment.

No further remark is needed.

The Pittsburgh Athletic Association, one of the prolific Benno Janssen’s most elaborate designs, as it was in 2000 before the recent renovation. Above, from across Fifth Avenue; below, from the grounds of the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial. Old Pa Pitt took these pictures with a Kodak Retinette, which comes close to his ideal of the perfect 35-millimeter camera.

Uptown is a strange neighborhood right now. A lot of development is going on, and a lot of decay is going on, and they are going on in the same blocks. This house is obviously not in perfect shape at the moment, but it was just recently declared a city historic landmark—partly for its architecture, but mostly for its associations.

Joe Tito was a bootlegger during Prohibition; when Prohibition ended, he invested the proceeds of his crimes in what was now legitimate business and bought the Latrobe Brewing Company, which had existed before Prohibition but had been closed for years. In 1939 he introduced the Rolling Rock brand, which was brewed in Latrobe until it was bought and moved to New Jersey. (Latrobe, currently owned by the City Brewing Company of Wisconsin, now brews Iron City and Stoney’s and other contract brews.)

Joe’s best friend in the world was Gus Greenlee, the Black entertainment magnate from the Hill famous in jazz legend as the owner of the Crawford Grill. Mr. Greenlee bought the equally legendary Pittsburgh Crawfords baseball team, and Mr. Tito invested in it.

The historic designation for this house came after much acrimonious debate. The owner of the property opposed it, since the house itself is not valuable but the property stands in an area that may soon be desirable. Some of the other opponents opposed on the grounds that the house was associated with organized crime, which suggests a strange view of what constitutes “history”: it is something like saying that the Marne should not be a historic battlefield because it is associated with the Kaiser. If historic buildings cannot be associated with sinners, then the only city with any historic buildings at all will be the New Jerusalem.

Now that it’s historic, what is to be done with this house? That is the interesting question. Uptown is rapidly developing as a neighborhood of urban loft apartments; is there any room for a single-family house? Is the house big enough to divide into profitable apartments? Or will it mysteriously catch fire some night?

We should note that Fifth Avenue is the dividing line between neighborhoods on city planning maps, which technically puts this house in the Crawford-Roberts section of the Hill. Ordinary Pittsburghers think of both sides of Fifth Avenue as Uptown, however, and most of the media reports about this house have mentioned Uptown as the neighborhood.

If the plans go through, this building is about to undergo a curious transformation: it will be surrounded by and encrusted with new development, leaving the façade exposed. It was originally the Mugele Motor Inn. (In the early days of the automobile, “Motor Inn” was a popular name for a garage.) More recently it belonged to the city Department of Public Works. It has a good location across from the restored Fifth Avenue High School, and it will be along the new “bus rapid transit” line to Oakland.

Someone left one of those temporary storage modules in front of the building, which mars our otherwise architecturally perfect picture of the Fifth Avenue façade. There is only so much old Pa Pitt can do.

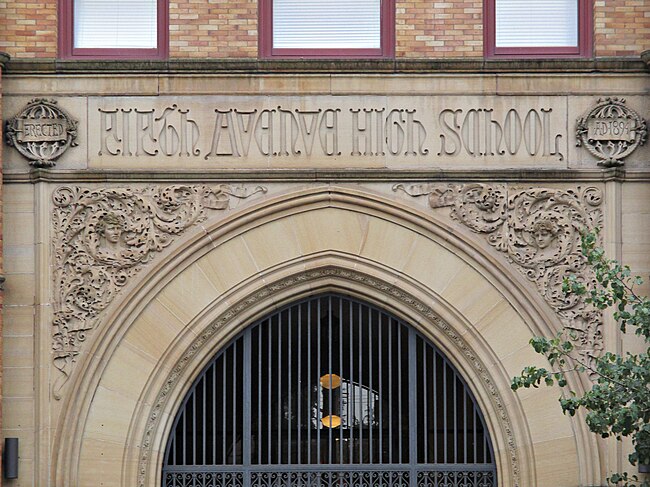

This Flemish Gothic palace, built in 1894, was designed by Edward Stotz, who would later give us Schenley High School. His son Charles Morse Stotz was more or less the founder of the preservation movement in Pittsburgh: he wrote the huge folio The Early Architecture of Western Pennsylvania, still an invaluable reference as well as a gorgeous book. It is fitting, therefore, that the father’s great landmarks have been among our preservation success stories.

The school was closed in 1976, and after that it sat vacant for more than three decades. A generation knew it only as that looming hulk Uptown. It is a tribute to the architect that it survived in fairly good shape. In 2009 it was finally brought back to life with a years-long restoration project that turned it into loft apartments, which sold well and suggested that there might be some potential in the Uptown neighborhood. (It certainly helped that the new arena—currently named for PPG Paints—opened at about the same time.)

These skyscraper dormitories were built in 1963 to designs by Dahlen Richey of Deeter & Richey. They were poetically named A, B, and C, but students immediately renamed them Ajax, Bab-O, and Comet.

The restored entrance looks like a scene from the modernist paradise that existed mostly in architects’ imaginations. But the original architect certainly did not specify the weirdly incongruous faux-antique lanterns.

This was built in 1896 as the First United Presbyterian Church; the architect was William Boyd, who gave the congregation the most fashionably Richardsonian interpretation of Romanesque he could manage. It was more or less in competition with the original Bellefield Presbyterian, of which only the tower now remains. But in 1967 the two congregations merged. They kept this building, renamed it Bellefield Presbyterian, and abandoned the old Bellefield Presbyterian up the street, which was later demolished for an office block.