The Highland Building looms behind the tiny shops of Ellsworth Avenue.

A Daniel Burnham design built for the McCreery & Company department store, this building opened in 1904. It originally had a classical base with a pair of arched entrances on Wood Street, but beginning in 1939 it had various alterations, so that nothing remains of the original Burnham design below the fourth floor. This was one of Burnham’s more minimalistic designs; in it we see how thin the wall can be between classicism and modernism.

Below, an abstract composition with elements of this building reflected in Two PNC Plaza across the street.

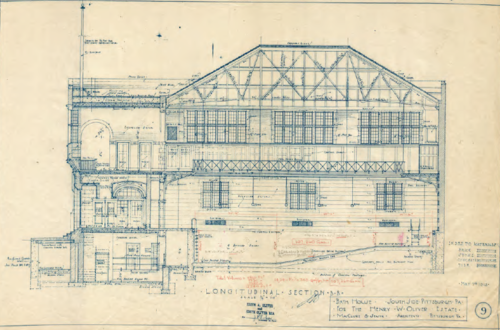

Known as the South Side Baths when it was built, this was donated by steel baron and real-estate magnate Henry W. Oliver, who in 1903 gave the city land and money for a neighborhood bathhouse to be free to the people forever. In those days, many poor families—including the ones who worked for Oliver—lived in tenements where they had no access to bathing. (Even the Bedford School across the street from this bathhouse had outside privies until 1912.) Oliver might not raise his workmen’s salaries, but he was willing to make the men smell better.

To design the bathhouse, Oliver chose the most prestigious architect in the country: Daniel Burnham. Then, in 1904, Oliver died, and his gift spent almost a decade in limbo. The project was finally revived in 1913, by which time Burnham had died as well. The plans were taken over by MacClure & Spahr, an excellent Pittsburgh firm responsible for the Diamond Building and the Union National Building. No one seems to know how much they relied on Burnham’s drawings, but the Tudor Gothic style of the building (it was finished in 1915) is certainly in line with other MacClure & Spahr projects, like the chapel for the Homewood Cemetery. Even MacClure & Spahr’s early sketches show a quite different building, so it is probably safest to assume that little of Burnham remains here.

There was a fad for building public baths in Pittsburgh in the early twentieth century, and on Saturday nights workers and their families would line up around the block to get into the bathhouses and wash off the grime of the week. Gradually, indoor plumbing became a feature of even the most notorious slum tenements, and all but one of the bathhouses closed. The Oliver Bathhouse, given to the people in perpetuity, remains. It has been saved by its indoor swimming pool, the only city pool open during the winter.

Nothing says “water” like a classical dolphin.

It was officially the Union Station, but there was no real union: the other important railroads (the B&O, the P&LE, the Wabash) had their own stations. Most Pittsburghers knew this as the Penn Station for the Pennsylvania Railroad, which owned it and ran most of the trains. Although this view was taken in 2001, little has changed: already the building was high-class apartments, and already the trains came into a dumpy little modern station grafted on the back. Here, on a day of patchy clouds, the afternoon sun shines a spotlight on the station’s most famous feature: the rotunda, one of Daniel Burnham’s most famous architectural achievements, so distinctive that it has its own separate listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

“Make no little plans,” said Daniel Burnham; “they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized.” The Chicago Tribune tells us the interesting story of the long search for the original source of that quotation, and the determination that it was in fact what Burnham said. It is probably the second-most-famous quotation from an architect in history: only Louis Sullivan’s “Form follows function” has been heard more often.

Outside Chicago, Pittsburgh was where the great Burnham was most prolific. Many of our most famous buildings—the Oliver Building, Penn Station, the Frick Building, and a good number of others—are by Burnham. Most of them are colossal. But the old Union Trust Company building—now the Engineers’ Society of Western Pennsylvania—was his first work here, and it is on a small scale. Small, but rich and perfect in its way. The front is a traditional Doric temple; the treatment of the top storey behind the pediment seems to enclose the temple in its own perfect world, insulated from the ugly realities of Fourth Avenue commercialism around it. It was built in 1898, and it can be seen as an answer and a rebuke to the tasteless extravagance of Isaac Hobbs’ 1870 Dollar Bank building across the street.

Everything in the Frick Building is gleaming white marble, with just enough accents to keep the interior from becoming entirely invisible. Above, the staircase at the Grant Street entrance. Below, the revolving doors and clock at the Grant Street entrance.

The lobby is shaped like a T, with a hall from the Grant Street entrance ending at the long hall from Forbes Avenue to Fifth Avenue, seen here from the Forbes Avenue entrance.

Even Henry Frick himself is gleaming white marble, rendered by the well-known sculptor Malvina Hoffman in 1923.

Louis Sullivan was of the opinion that Daniel Burnham’s success in the classical style was a great blow to American architecture. But what could be more American than a Burnham skyscraper? Like America, it melds its Old World influences into an entirely new form, in its way as harmonious and dignified as a Roman basilica, but without qualification distinctly American.