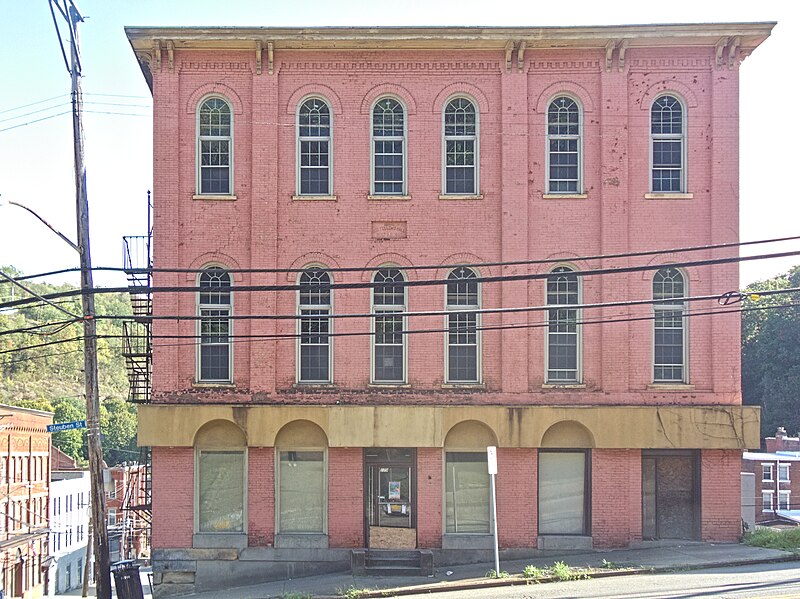

Father Pitt does not know the history of this building, and would be delighted to be informed. A real-estate site says it was built in 1920 (Update: The correct date is 1912 or 1913; see below). It is residential now, but it has the look of a club. That impression is strengthened by the brickwork double-headed eagle at the peak of the Ella Street front. Old Pa Pitt is ashamed to admit that he didn’t notice the eagle when he hurriedly snapped these pictures on his way between the Ukrainian National Home and St. Mark’s School, but you can see it pretty well if you enlarge the picture above, and it is a clever bit of bricklaying. The eagle’s heads seem to be sharing some sort of military cap. Was this an Albanian or Serbian club? (Update: We have heard from the McKees Rocks Historical Society that this was indeed Serbian, which explains the double eagle. And another update: The architect was McKees Rocks’ own John H. Phillips; the building was put up in 1912 or shortly after.)

The windows were arched originally; the arches have been bricked in so that the windows could be replaced with cheap stock models.

The two-storey section at the rear is a later addition, after 1923 to judge by old maps; it may have been added when the club was converted to a residence. The bricks are carefully matched to make the link between the parts seamless. The tops of the doorways, however, seem to have been bricked in at different times, one of them with almost-but-not-quite-matching brown bricks, and the other with ordinary red bricks.