Allegheny High School, now the Allegheny Traditional Academy, has a complicated architectural history involving two notable architects at three very different times.

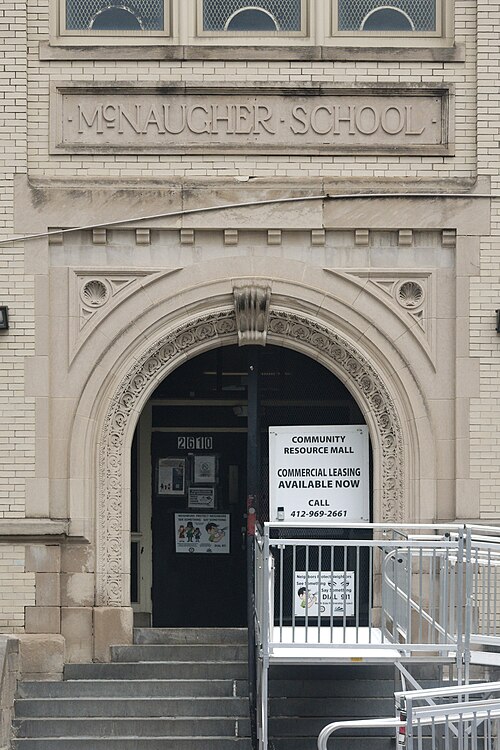

The original 1893 Allegheny High School on this site was designed by Frederick Osterling in his most florid Richardsonian Romanesque manner. This building no longer exists, but the photograph above gives us a good notion of the impression it made. The huge entrance arch is particularly striking, and particularly Osterling; compare it with the Third Avenue entrance of the Times Building, also by Osterling.

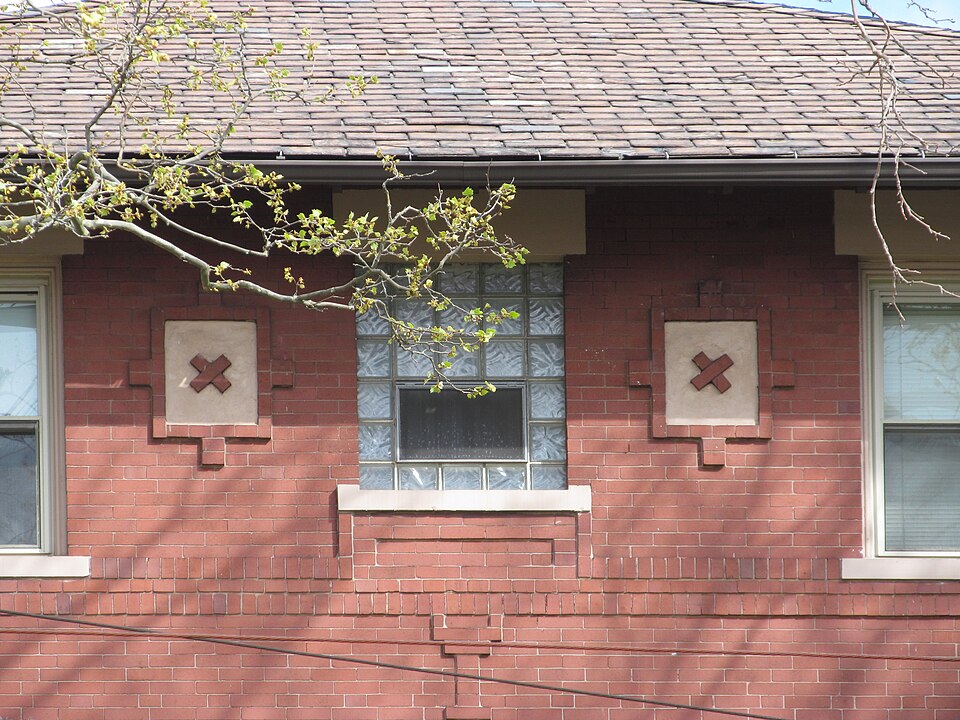

In 1904, the school needed a major addition. Again Osterling was called on, but by this time Richardsonian Romanesque had passed out of fashion, and Osterling’s own tastes had changed. The Allegheny High School Annex still stands, and Osterling pulled off a remarkable feat: he made a building in modified Georgian style that matched current classical tastes while still being a good fit with, and echoing the lines of, the original Romanesque school.

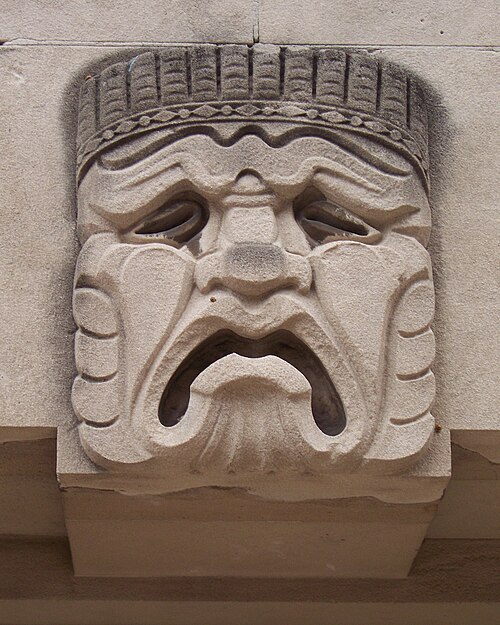

The carved ornaments on the original school were executed by Achille Giammartini, and we would guess that he was brought back for the work on the Annex as well.

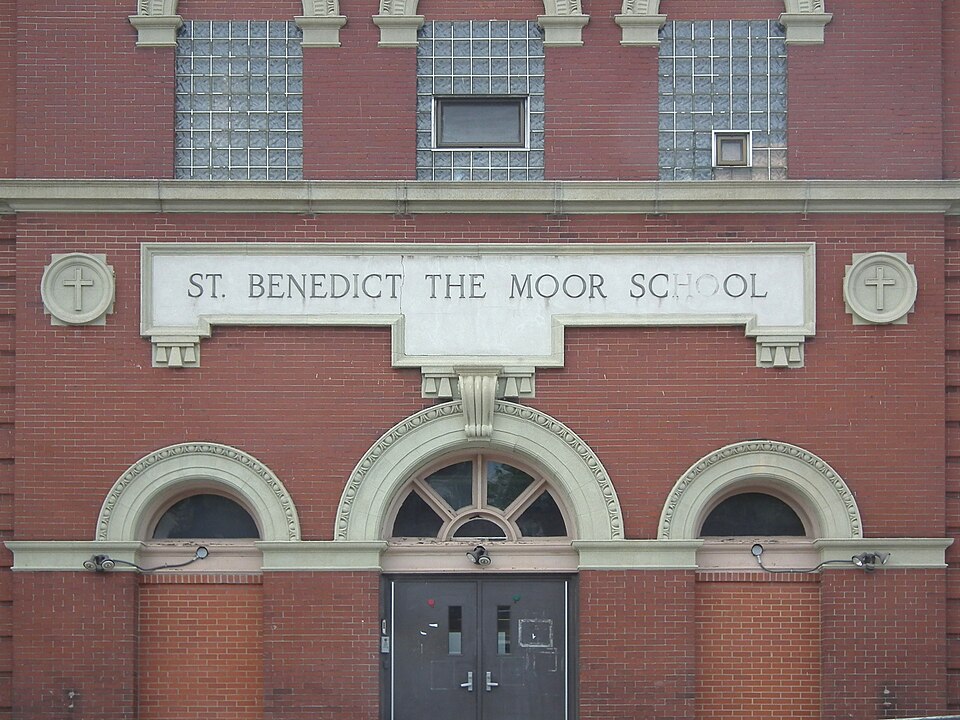

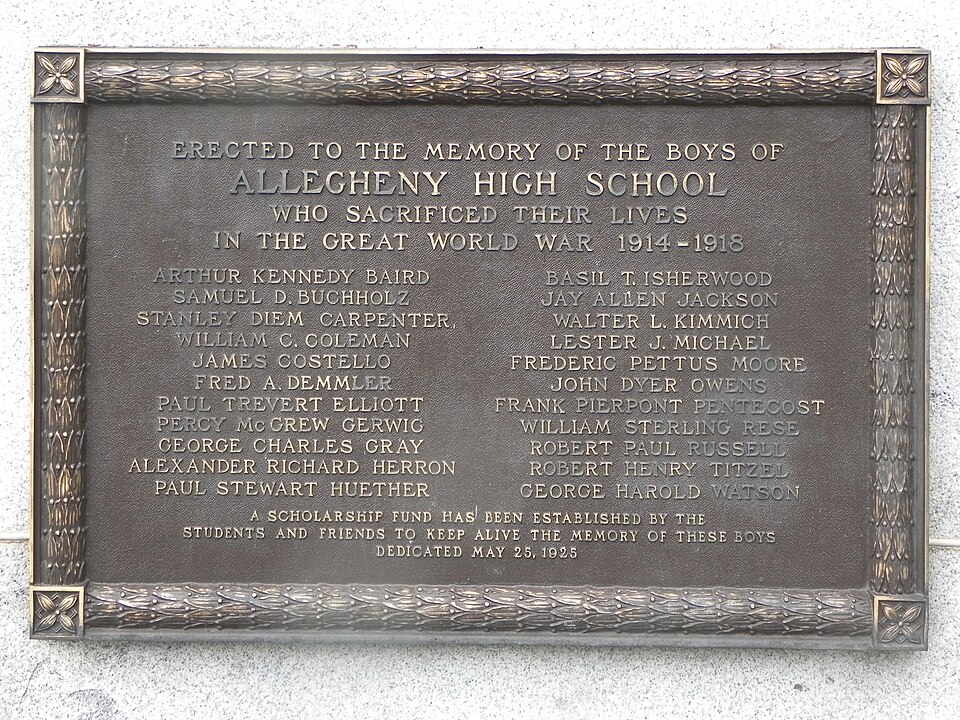

A war memorial on the front of the Annex. Twenty-two names are inscribed. Everyone who went to Allegheny High in those years knew someone who was killed in the Great War.

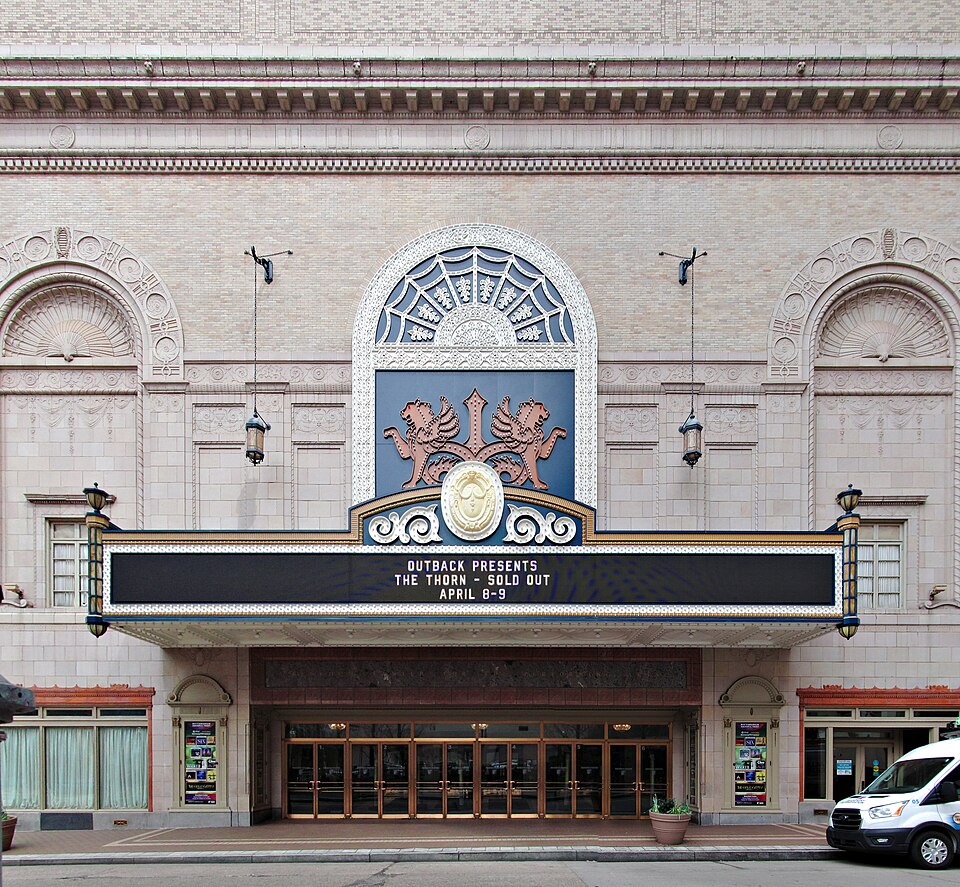

By the 1930s, the school was too small again. The original school was torn down, and Marion Steen, house architect for Pittsburgh Public Schools (and son of the Pittsburgh titan James T. Steen) designed a new Art Deco palace nothing like the remaining Annex. The two buildings do not clash, however, because there are very few vantage points from which we can see both at once.

The auditorium has three exits, each one with one of the three traditional masks of Greek drama above it: Comedy, Meh, and Tragedy.

Comments