The Beezer Brothers designed Wilkinsburg’s miniature skyscraper for real-estate developer and brewer Leopold Vilsack. It was built in 1902.1 It had been announced as the Vilsack Building; Vilsack named it the Carl Building (after his son) while it was still under construction; later it was called the Shields Building. It holds a curious place in the history of public housing: it was converted to apartments for senior citizens in 1975 as the first Section 8 housing project.

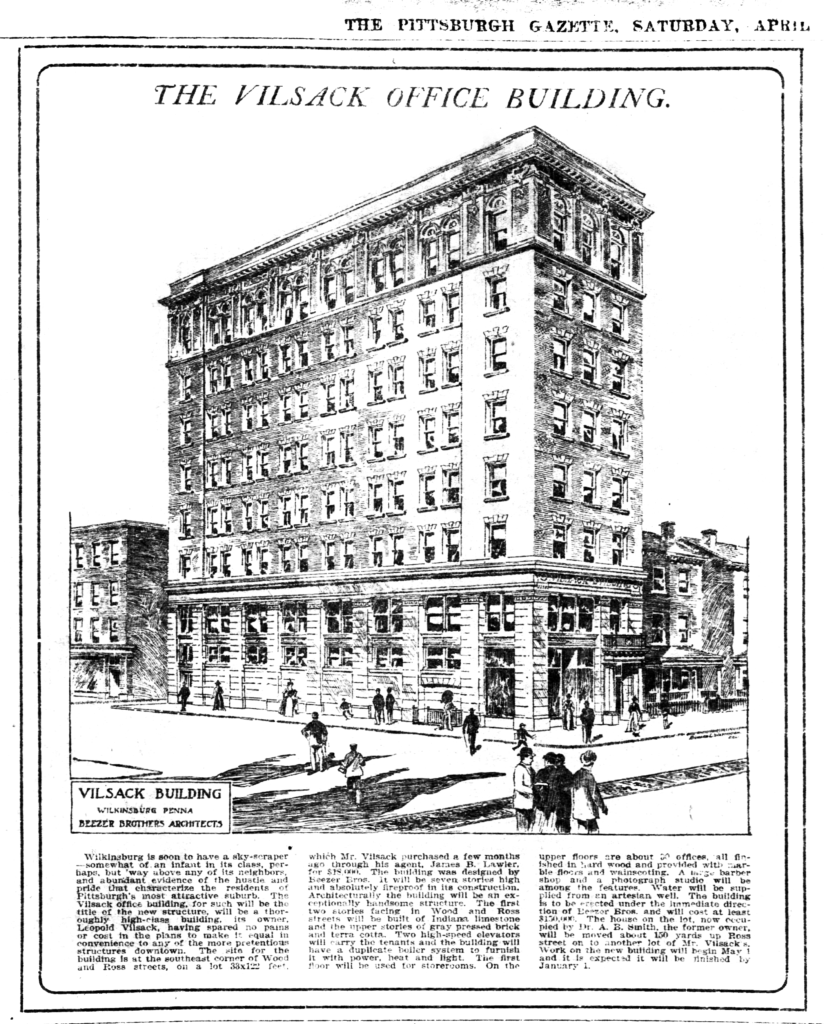

The Beezers’ rendering of the proposed building appeared in the Gazette for April 12, 1902:

You may notice, if you count carefully, that the building lost a floor between initial design and construction.

We transcribe the caption under the drawing:

Wilkinsburg is soon to have a sky-scraper—somewhat of an infant in its class, perhaps, but ’way above any of its neighbors, and abundant evidence of the hustle and pride that characterize the residents of Pittsburgh’s most attractive suburb. The Vilsack office building, for such will be the title of the new structure, will be a thoroughly high-class building, its owner, Leopold Vilsack, having spared no pains or cost in the plans to make it equal in convenience to any of the more pretentious structures downtown. The site for the building is at the southeast corner of Wood and Ross streets, on a lot 33×122 feet, which Mr. Vilsack purchased a few months ago through his agent, James B. Lawler, for $18,000. The building was designed by Beezer Bros. It will be seven stories high and absolutely fireproof in its construction. Architecturally the building will be an exceptionally handsome structure. The first two stories facing in Wood and Ross streets will be built of Indiana limestone and the upper stories of gray pressed brick and terra cotta. Two high-speed elevators will carry the tenants and the building will have a duplicate boiler system to furnish it with power, heat and light. The first floor will be used for storerooms. On the upper floors are about 90 offices, all finished in hard wood and provided with marble floors and wainscoting. A large barber shop and a photograph studio will be among the features. Water will be supplied from an artesian well. The building is to be erected under the immediate direction of Beezer Bros. and will cost at least $150,000. The house on the lot, now occupied by Dr. A. B. Smith, the former owner, will be moved about 150 yards up Ross street on to another lot of Mr. Vilsack’s. Work on the new building will begin May 1 and it is expected it will be finished by January 1.

It is interesting to note that, if you visit the building today, you will once again find “a large barber shop” among the features.

Comments