Like the rectory behind it, this is a simple and dignified Renaissance palace that sets off the flamboyant Gothic of Holy Rosary Church.

Like the rectory behind it, this is a simple and dignified Renaissance palace that sets off the flamboyant Gothic of Holy Rosary Church.

You might pass this little building by without a second glance as you walked along Poplar Street, if you ever did walk along Poplar Street (a very pleasant street) in Castle Shannon. But if you did pause, you might notice the tall Corinthian columns and sturdy-looking quoins (those patterns in the bricks that are meant to look like cut stone) and think, “I wonder whether that used to be a bank.”

Then you would look up at the pediment, and all doubt would be removed.

The electric vault alarm still sits prominently in the pediment where a richer bank might have had an allegorical figure of Commerce.

To judge by old maps, this bank was built between 1890 and 1906.

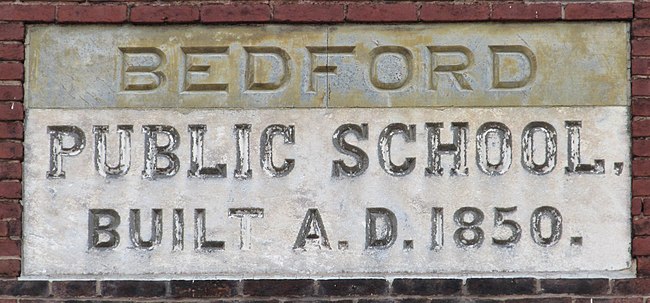

Built in 1850 for the borough of Birmingham, this is the oldest public-school building left in the city of Pittsburgh. It was built in the still-fashionable Greek Revival style, and it originally had a cupola in which the Birmingham town clock was installed. It remained a school of some sort until 1960; then it was sold to be used as a warehouse. In 1997 it was converted into lofts by serial restorationist Joedda Sampson, who has left a trail of beautiful restorations wherever she went.

Note the identical but separate entrances. As in many mid-nineteenth-century schools, one was for girls and one was for boys.

If your eye detects a not-very-subtle difference between the name “Bedford” and the rest of the inscription, you can tell your eye that it is because the old Birmingham Public School No. 1 was renamed after Birmingham was taken into the city of Pittsburgh in 1872. The name “Bedford” honors Dr. Nathaniel Bedford, who had been a surgeon at Fort Pitt before the Revolution, and later laid out the borough of Birmingham on his wife’s family’s land.

The Mellon Institute of Industrial Research was founded as part of the University of Pittsburgh, and this was its home for the first two decades of its life. When the Mellon Institute declared its independence, it moved to its palatial quarters out Fifth Avenue, and the old Mellon Institute building became Allen Hall at the University of Pittsburgh.

The building, which opened in 1915, was designed by J. H. Giesy, and it was properly classical to match Henry Hornbostel’s slightly mad plan of making the University a new Athenian Acropolis in Pittsburgh. (The plan was later abandoned in favor of Charles Z. Klauder’̑s much madder plan of a skyscraper university.)

The richly detailed bronze doors are unique.

The building is precisely located for the best vista up Thackeray Street.

Here is a picture of the building when it was new in 1915:

And old Pa Pitt has duplicated that picture for you in 2022, because that is the kind of effort he puts into serving his readers:

Nothing about the exterior has changed except the plantings, and even those have been reduced to show off the building: a few years ago much of the front was obscured by trees.

The Maul Building, built in 1910, was designed by the William G. Wilkins Company, the same architects who did the Frick & Lindsay building (now the Andy Warhol Museum). Both buildings are faced with terra cotta, and both lost their cornices—the one on the Andy Warhol Museum has been carefully reconstructed from pictures, but the one here is just missing. The rest of the decorations, though, are still splendid.

Old Engineering Hall at the University of Pittsburgh is a fairly successful marriage of modernism and classicism. It is almost postmodern avant la lettre, with classically inspired details but a shape that owes nothing to the classical world. It was built in 1955, when it was still common for modernist buildings to apologize for themselves by including a few dentils and a suggestion of a Greek-key frieze. This was Engineering Hall for only about fifteen years; the School of Engineering moved out in 1971 (into the uncompromisingly modern Benedum Hall), and since then this building has been put to such miscellaneous uses that the university has never been able to come up with a better name for it than “that building that used to be Engineering Hall.”

This fine little Renaissance palace, built in 1896, was the first of Carnegie’s branch libraries, and thus arguably the vanguard of the whole idea of branch libraries. It was also the first public library with open stacks, where patrons would just walk to the shelf and pick up the book by themselves. In other libraries—including much of the main Carnegie in Oakland until a few years ago—the patron would ask for the book at the desk, and a librarian would run back to the mysterious stacks and fetch it.

Like all the original libraries in the Carnegie system, this was designed by Alden & Harlow.

This severely classical building was built in about 1925 to a design by architect Abram Garfield, the son of martyred president James A. Garfield, and it looks as though nothing could possibly set fire to it. It passed into the hands of the University of Pittsburgh in 1968, and is now known as Thackeray Hall.

After the flamboyant Gothic of Holy Rosary, this stately Renaissance palace is quite a contrast.