The ornate cap of the Benedum-Trees Building, with the PPG Place Christmas tree poking its head into the picture. Enlarge the images to appreciate the wealth of carved detail.

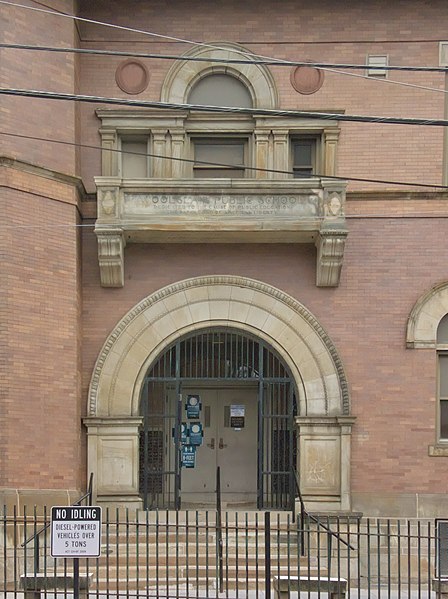

This fine Renaissance palace, built in 1897, was designed by Samuel T. McClaren. It sits on 40th Street at Liberty Avenue, where it is technically—according to city planning maps—in Bloomfield. Most Pittsburghers, however, would probably call this section of Bloomfield “Lawrenceville,” since it sticks like a thumb into lower Lawrenceville, and the Lawrenceville line runs along two edges of the school’s lot.

For some reason the style of this building is listed as “Romanesque revival” wherever we find it mentioned on line. Old Pa Pitt will leave it up to his readers: is this building, with its egg-and-dart decorations, false balconies, and Trajanesque inscriptions, anything other than a Victorian interpretation of a Renaissance interpretation of classical architecture? Now, if you had said “Rundbogenstil,” Father Pitt might have accepted it, because he likes to say the word “Rundbogenstil.”

Update: Father Pitt regrets to say that this building has been demolished to make way for a much larger facility.

An elegant little classical firehouse, still in use as a medic station, on Lafayette Avenue at the corner of Federal Street. It dates from before 1910 and after 1903, according to the Pittsburgh Historic Maps site.

In the early twentieth century, the Hill was Pittsburgh’s most diverse neighborhood, and in particular it was the main center of Jewish culture. A number of buildings survive from the Jewish community there, though they have all been turned to other uses. This one, for example, is now a “community engagement center” run by the University of Pittsburgh. But it was the original home of the Hebrew Institute, which moved to Squirrel Hill in 1944. It was a school that taught Hebrew language, literature, and culture to Jewish children. The style of the building is typical Pittsburgh School Classical, but the broken pediment above the entrance frames a Torah scroll.

Addendum: The architect, according to a 1914 issue of the Construction Record, was Walter S. Cohen, who had a thriving practice serving mostly Jewish clients. “Architect Walter S. Cohen, Oliver building, has plans nearly completed for a two-story brick and stone institute building for the Hebrew Institute of Pittsburgh, Wylie avenue and Green street, to be built at a cost of $30,000.”

One of the little neighborhood libraries designed by Alden & Harlow, this one has a prime location on Grandview Avenue, making it possibly the library with the best view in the world.