Old Pa Pitt’s New Year’s resolution is to bring you more of the same, and to try to get better at it.

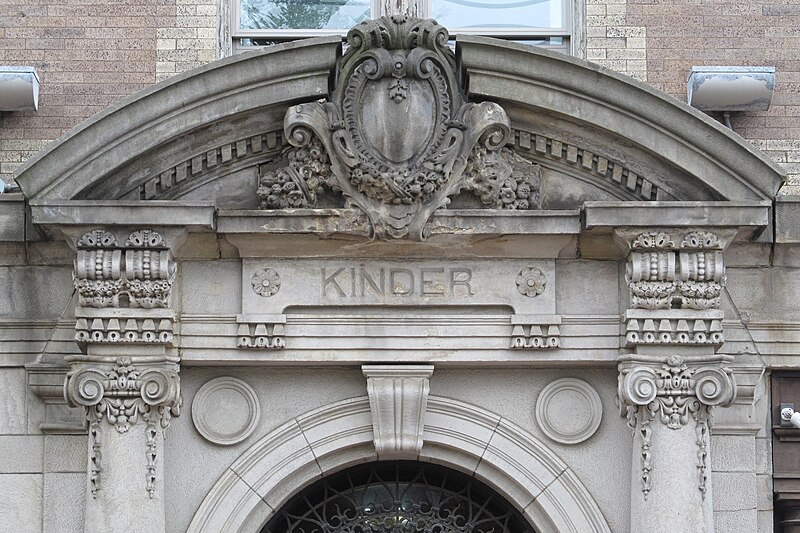

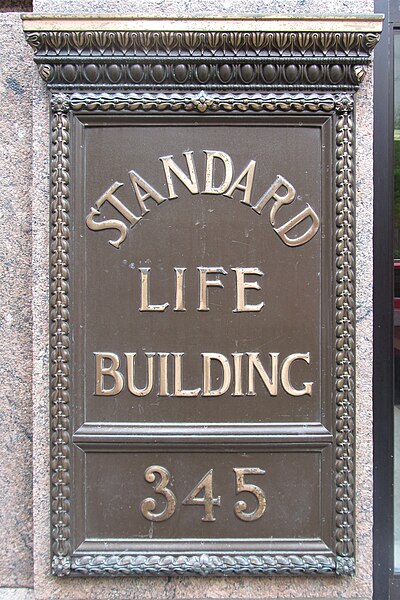

The May Building was designed by Charles Bickel, probably the most prolific architect Pittsburgh ever had, and a versatile one as well.

The famous Sicilian Greek mathematician and philosopher and inventor and scientist Archimedes was nicknamed “Beta” in his lifetime, because he was second-best at everything. That was Charles Bickel. If you wanted a Beaux Arts skyscraper like this one, he would give you a splendid one; it might not be the most artistic in the whole city, but it would be admired, and it would hold up for well over a century. If you wanted Richardsonian Romanesque, he could give it to you in spades; it might not be as sophisticated as Richardson, but it would be very good and would make you proud. If you wanted the largest commercial building in the world, why, sure, he was up to that, and he would make it look so good that a century later people would go out of their way to find a use for it just because they liked it so much.

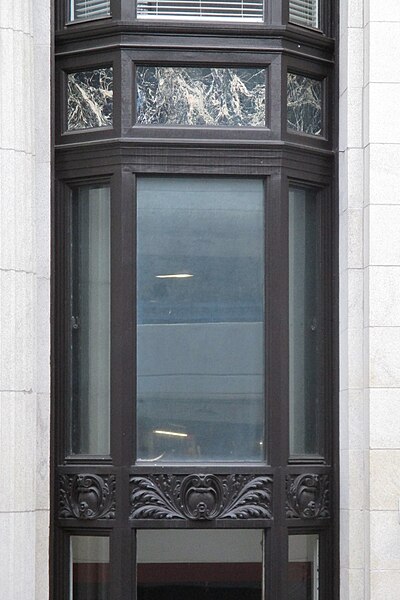

The modernist addition on the right-hand side of the building was designed by Tasso Katselas.