At the corner of Seventh Avenue and William Penn Place is a complicated and confused nest of buildings that belonged to the Bell Telephone Company. They are the product of a series of constructions and expansions supervised by different architects. This is the biggest of the lot, currently the 25th-tallest skyscraper in Pittsburgh, counting the nearly completed FNB Financial Center in the list.

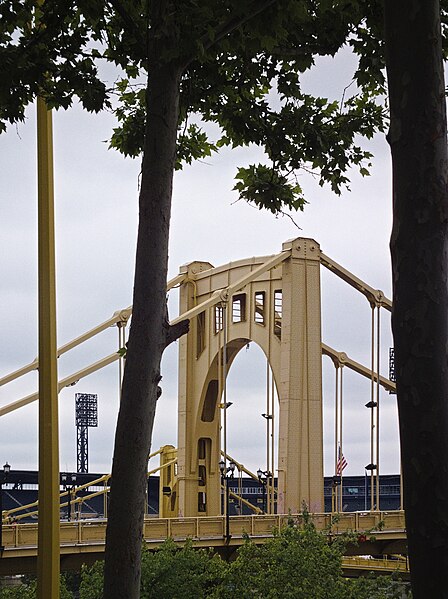

The group started with the original Telephone Building, designed by Frederick Osterling in Romanesque style. Behind that, and now visible only from a tiny narrow alley, is an addition, probably larger than the original building, designed by Alden & Harlow. Last came this building, which wraps around the other two in an L shape; it was built in 1923 and designed by James T. Windrim, Bell of Pennsylvania’s court architect at the time, and the probable designer of all those Renaissance-palace telephone exchanges you see in city neighborhoods. The style is straightforward classicism that looks back to the Beaux Arts skyscrapers of the previous generation and forward to the streamlined towers that would soon sprout nearby.

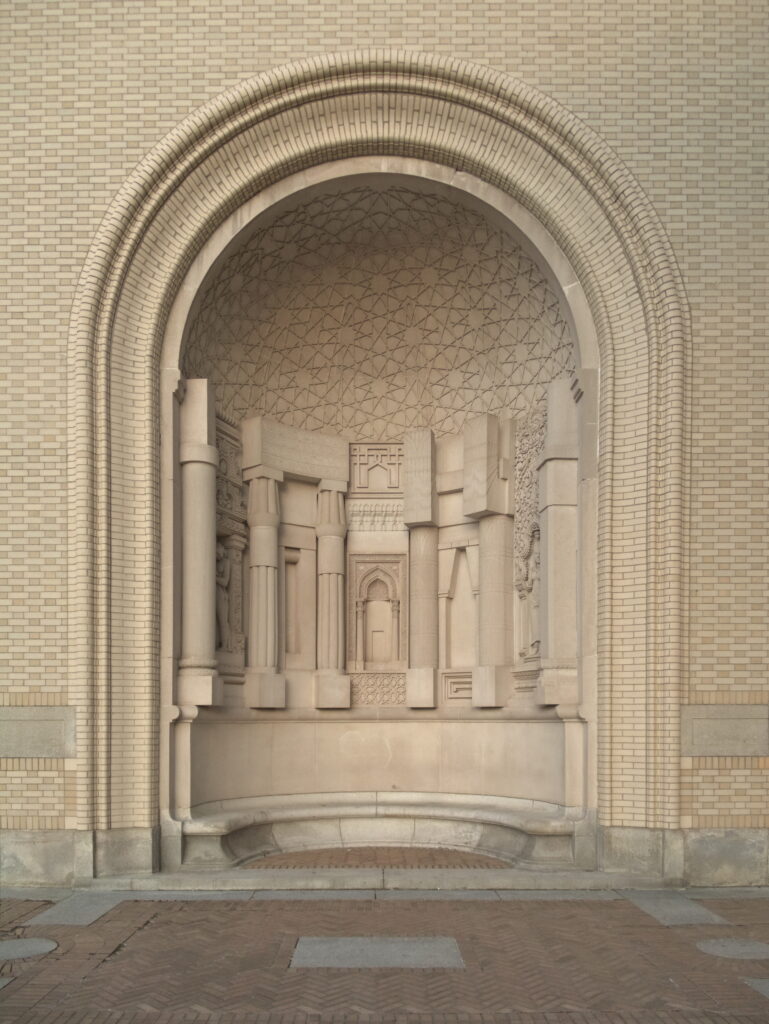

Hidden from most people’s view is a charming arcade along Strawberry Way behind the building.