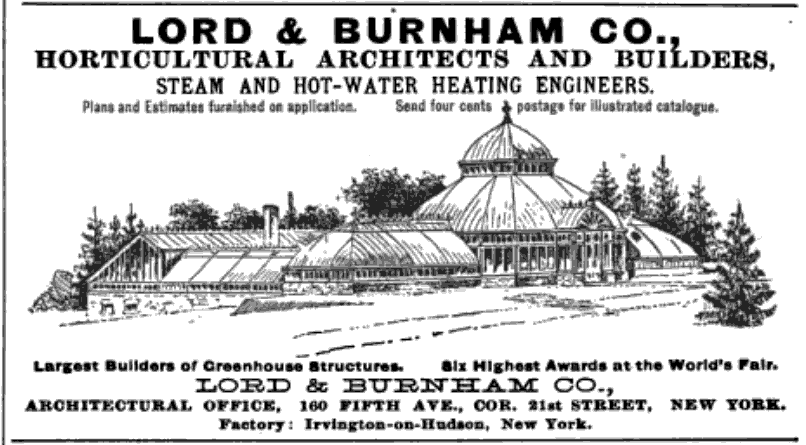

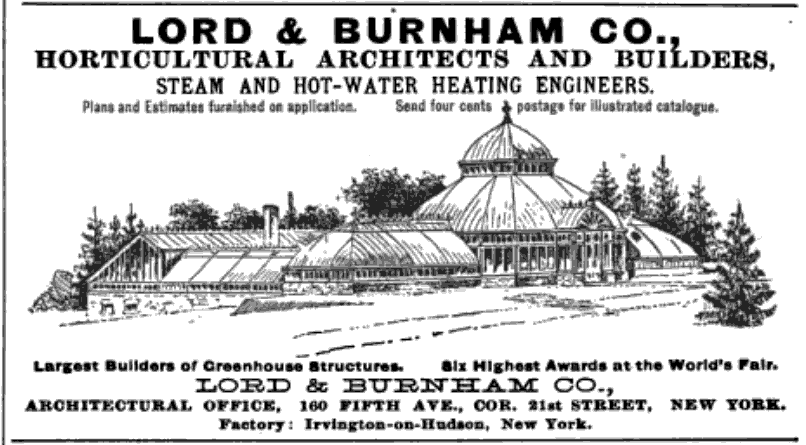

Lord & Burnham designed Phipps Conservatory in 1892, which was probably their biggest commission ever; and in this 1896 advertisement for their services, we see them showing a model conservatory that is very much like one of the wings of Phipps.

Lord & Burnham designed Phipps Conservatory in 1892, which was probably their biggest commission ever; and in this 1896 advertisement for their services, we see them showing a model conservatory that is very much like one of the wings of Phipps.

This Italianate house has been altered to make it into a duplex, and it is continuing its adventures. That rectangular front window on the filled-in section was added only this past year. But the rest of the house looks very much the way it did when it was built in the 1870s or thereabouts.

The September 1915 issue of The Builder published this picture of the Concord Presbyterian Church in Carrick, along with this description:

An interesting building, published in this issue, built after the style of the early English Parish Church, and executed in that character exceptionally well both interior and exterior.

The exterior of the Church is of Rubble Masonry which as a material blends well with the immediate surroundings, the site being on Brownsville Road, Carrick, and of a rural atmosphere. The interior (as the interior of the early English Parish Church) is carried out in a very simple but dignified design, of plaster and timber, finished in a warm color scheme.

The Church has a seating capacity of 500, the Sunday School accommodating 450.

The architect, as the page with the photograph above tells us, was George H. Schwan. Although the immediate surroundings were “of a rural atmosphere” in 1915, they would not remain that way for long. Already in the photograph above you can see the great engine of urbanization: streetcar tracks.

This is the way the church looks today, with its early-settler country churchyard behind it and the decidedly non-rural business district of Carrick in front of it. More pictures of the Concord Presbyterian Church are here.

On a street of mostly small vernacular rowhouses, this pair of grand Second Empire houses dominates the streetscape. They are well preserved and well cared for, and we need no more excuse to appreciate the details.

This front entrance (could you guess that the picture was taken the day after Halloween?) bears an unusual memento of the original owner of the house:

Note the monogram on the side of the steps. An 1890 map shows that the house belonged to a Jonathan Seibert.

Note the exceptionally elaborate door on the breezeway.

This church has a complicated history that perhaps someone from Brighton Heights could help old Pa Pitt sort out. It was built in 1907 as a Congregational church, replacing an earlier frame building. By 1923 it was the Eleventh United Presbyterian Church. Now it belongs to the Greater Allen African Methodist Episcopal congregation, which has kept it in beautifully original shape, right down to the uncleaned black stones, which Father Pitt loves.

Imagine the uproar that would ensue if your city government today decided to hire a Beaux-Arts master like Thomas Scott to design a monumental palace for such a utilitarian purpose as a water-pumping station. Imagine the inquiries that would probe the vital questions of how much each of those carved faces cost and why stone trim was used when the same object could be accomplished with aluminum. The world has made a lot of progress since Scott, architect of the Benedum-Trees Building downtown (where he kept his architectural office, naturally), gave us this $100,000 pumping station on an out-of-the-way street on the South Side Slopes.1

There were doubtless security reasons for bricking in the towering windows that used to flood the place with light. But Father Pitt cannot help suspecting that the real reason is that the workers here constituted a sort of men’s club, and men’s clubs in Pittsburgh abhor natural light.

Even in November, much of the building is obscured by trees.

John T. Comès designed the older Holy Innocents Church, which was replaced by the cathedral-sized church that stands today, and it is likely that he designed this school as well. The style is a kind of Art Nouveau Jacobean. It is vacant right now, which puts it in danger, since large vacant buildings are attractive nuisances both for arson and for blue “Condemnation” stickers.

Painting the stone accents grey may have been someone’s solution to the soot problem. It was not a good idea.

The Hunting-Davis Company was a versatile firm, but its specialty was industrial architecture. The McKinney Manufacturing Company warehouse was noted as an innovation in reinforced-concrete construction when it went up in 1914, and it still stands in very close to its original form, giving us a good look at the ultra-modern industrial architecture of the early twentieth century. We note that even such a utilitarian structure as a warehouse was not allowed to go up without some elegant Art Nouveau ornamentation:

Here is the architects’ Liverpool Street elevation as it appeared in an article in the Construction Record for February 7, 1914:

And here is the same building today:

This is the Preble Avenue side, which is shorter by one bay but otherwise similar. Old Pa Pitt would have preferred to duplicate the architects’ drawing as closely as possible, but Liverpool Street no longer exists in that block: it has been filled in with lower buildings.

Here is the text of the article, which will be of interest to students of architecture and construction:

Last week the contract for building the warehouse for the McKinney Manufacturing Company, Northside, Pittsburgh, was placed with the Henry Shenk Company, Pittsburgh. The building as designed by the Hunting-Davis Company, Century building, Pittsburgh, will be approximately 105×120 feet, six stories high with basement. It will be of reinforced concrete throughout. There will be no steel beams or girders used in the construction work except those for the outside lintels and elevator framing.

In order that the reinforced concrete work may be properly constructed, thus eliminating any possibility of poor workmanship and accidents, it is agreed that superintendent of five years experience on reinforced concrete building must remain on the work at all times. The mixture of the concrete will be one part cement, two parts sand and four parts gravel. All columns will have a one to two cement and sand mortar placed to a depth of three inches before the concrete is placed. The columns will be cast a day ahead of the beams and slabs. Care is to be exercised in removing the forms so that no board marks or imperfections on the exterior of the building are noticeable.

The building will be one of the heaviest loaded flat slab buildings ever designed in the country. A four-way diagonal reinforcement will be used in the slab construction. The columns will have hoop-reinforced concrete. All ceilings will be flat. The floor loads per square foot will be as follows: First floor, 800 pounds; second floor, 1,200 pounds; third floor, 650 pounds; fourth floor, 450 pounds; fifth and sixth floors, 300 pounds. The basement floor and walls will be reinforced to take care of flood water pressure with flood gates on basement windows.

The design carries with the proposed work the building of a tunnel to connect with the present plant and the construction of a bridge to connect up with the second floor. Solid steel sash will be used on all windows. A sprinkler system will be installed. All floors in the basement tunnel and pent houses will have a granolithic finish.

For the connecting bridge the walls and roof will be constructed of self-centering material plastered with cement mortar. The walls will be two inches thick and finished smooth on both sides. The roof will be two and one-half inches thick and finished with a smooth under coat. Composition roofing will be used throughout all the work.