…at the Koppers Building (left) and the Gulf Building (right).

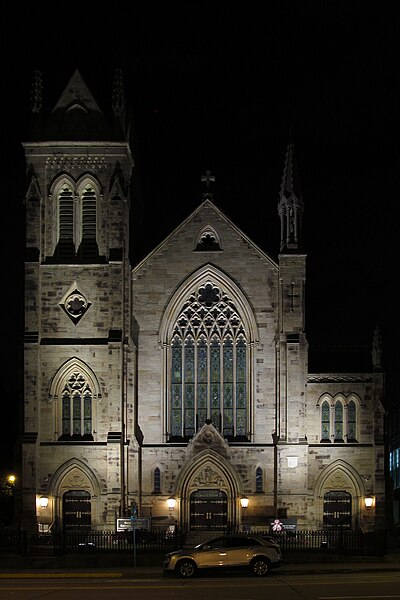

Now Emmaus Deliverance Ministries. Designed by John Lewis Beatty, this late-Gothic-style church was built in about 1925. (The cornerstone has been effaced, which old Pa Pitt regards as cheating, though he understands that a new congregation likes to make a new beginning.)

A Gothic church must maintain a delicate balance: it wants to be impressive, but it also wants to be welcoming. The simple woodwork over the entrances (this one is the basement entrance) gets the balance right: it fits well with the style of the building, matching the angle of the Gothic arches, but it sends the message that we’re just plain folks here.

Coffey Way in downtown Pittsburgh. This is not only the best picture of the year, but possibly the best one old Pa Pitt has ever published. He took a number of photographs from more or less this same angle, but when the barely visible figures in dark clothing wandered into the frame, he knew this would be the one.

If old Pa Pitt were at all concerned about his reputation as an artist, he would publish about one picture a week, if that many. Art is not his primary purpose here, however. His aim is to document the treasures that surround us, and he is willing to accept second-rate pictures if they show the object reasonably well. Sometimes, however, he does try to aim a little higher than that. These are some of his favorite pictures from the past year, not because of what they depict, but purely as photographic compositions.

The Childes-Callery-Casey-Falk House, now the Chancellor’s Residence for the University of Pittsburgh. It was designed by Peabody & Stearns and built in 1897. This was a perfect late-fall day, and in spite of the temptation to turn up the saturation to bring out the colors of the leaves, the picture seemed to work best when it was a little less colorful and just slightly melancholy.

St. Peter’s Church on the North Side. For this picture, Father Pitt actually hauled a tripod down to the North Side. He does not usually put that much effort into anything, so this one gets on the list just because it was extra work.

Dandelion seeds.

The onion domes on Holy Virgin Russian Orthodox Church in Carnegie, lightly dusted with snow. It took a fair amount of fiddling to get the domes and the crosses and the subtle clouds behind them all at the right shades.

The entrance to the Kinder Building in Allegheny West. At night the Beaux-Arts architecture takes on just the right air of mystery; we expect to see Humphrey Bogart emerge and be accosted by a shadowy figure in a trench coat.

Fall in the Union Dale Cemetery.

Bridges on the Monongahela. Taken from the south shore, this picture seems to tell the story of an urbanized river.

Myosotis laxa, the Lesser Forget-Me-Not.

Urn with resting fawn, Allegheny Cemetery.

The Peoples Building, McKeesport. Sometimes Father Pitt must admit that the weather has more to do with making a good picture than the skill of the photographer. In this case, he can take some credit for using a red filter to bring out the contrast between sky and clouds, but otherwise it was just a perfect day.

Penstemon digitalis, the Foxglove Beardtongue. This is a good picture of a flower taken under unfavorable conditions: bright sunlight wipes out details and makes it hard to get good botanical pictures. One solution is the one adopted in this picture, which is to have the sun shining through rather than on the flowers.

The entrance to St. Francis Xavier Church in Brighton Heights, designed by William P. Hutchins. This picture is made from a stack of three photographs at different exposures.

The Trimont (designed by Lou Astorino), seen in silhouette. It is not old Pa Pitt’s favorite building in the city, but certain views have dramatic photographic possibilities.

A very patriotic streetcar picture from Beechview.

Winter branches against sunset clouds.

What’s at the end of the rainbow? A streetcar, of course.

The rotunda of Penn Station is such a remarkable structure that it has its own separate listing with the Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation. The skylight is a fine example of abstract geometry in metalwork.

The current owners of the Pennsylvanian hate photographers and tourists who come up to see the rotunda, and post signs on the walk up to the rotunda warning that this is private property and no access beyond this point and, with dogged specificity, NO PROM PHOTOS. But old Pa Pitt walked up through the parking lot, taking pictures all the way, and therefore saw the signs only on the way back. Sorry about that, all ye fanatical upholders of the rights of private property, but these pictures have already been donated to Wikimedia Commons, so good luck getting them taken off line.

The four corners of the earth, or at least the four corners of the Pennsylvania Railroad, are represented on the four pillars of the rotunda.

“Pittsburg” was the official spelling, according to the United States Post Office, when the rotunda was built in 1900.

Allegheny General is one of the few classic skyscrapers in Pittsburgh outside downtown. It was built in 1926; the architects were York & Sawyer. These views were taken with a long lens from across the Allegheny River.

Below, with bonus pigeons:

A change in the light makes quite a different picture:

All the South Side histories tell us that this school was originally built in 1871, the year before Birmingham was taken into the city of Pittsburgh as part of the South Side. From old maps, however, it appears that only the central part of the school, invisible from the street today, was built that early. The two identical fronts, this one on 15th Street and the other on 14th Street, seem to date from the 1880s. In 1940, the building was sold to St. Adalbert’s parish up the street, which used it as a middle school. It spent more than sixty years as a Catholic school of one sort or another. The last incarnation of the Catholic school closed in 2002, and after that the school—like all the other closed schools on the South Side—was converted to apartments.

This building, put up in 1930–1931, was a branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, and the Clevelanders Walker & Weeks were the architects—but with Henry Hornbostel and Eric Fisher Wood as “consulting architects.”1 Old Pa Pitt doesn’t know exactly how far the consulting went. At any rate, the architects chose sculptor Henry Hering, who had done several prominent decorations in Cleveland, to create the cast-aluminum reliefs for this building. The picture below is from 2015, but it will serve to show the placement of the reliefs:

The three main figures are obviously allegorical; they seem to represent industry, agriculture, and the professions.

Benno Janssen, Pittsburgh’s favorite architect for clubs of all sorts, designed this small skyscraper, which was built in 1923. The view above is an attempt at a perspective rendering something like what Janssen would have shown the clients. It is actually impossible in our narrow streets, so old Pa Pitt had to divide the picture into multiple planes and ruthlessly distort them. If you enlarge the picture, you can see some of the comical effects of that distortion; but the building itself looks about right now.

This building received a glowing review from one of Janssen’s fellow architects in the April, 1926, issue of the Charette, the magazine of the Pittsburgh Architectural Club:

PITTSBURGH’S DOWNTOWN Y. M. C. A.

Much has been said from time to time in favorable comment of some of our older important buildings, but thus far nothing has been noted to the writer’s attention with respect to some of the more recent structures. To make particular mention—the Downtown Y. M. C. A. building. A building of the high building category, worthy in its class of as favorable comment architecturally as other buildings of our city renowned in their type. Among the higher buildings erected in recent years throughout the county, it is difficult to select one which surpasses the Y. M. C. A. in point of satisfying design. It is of modern interpretation. A building unified, in which the base shaft and top are related parts, knit together in harmonious composition, enhanced by well studied use of materials and nicety of restraint in carefully selected details. It is a building of design vastly in contrast to many of the present era, whose corresponding parts placed one on top of the other without apparent relation other than the different portions may bear a strain or similarity of type.

A building to be judged architecturally must be viewed with a knowledge or at least an understanding of the limiting conditions under which, and more often in spite of which, a design is created. Thus a cathedral, a masterpiece, may not exceed in architectural attainment that of a small parish church. An extensive mansion may not be better architecturally than a small cottage, though the problems and limitations of both are not comparable. One might not say in comparing the fine church with the fine mansion that one is fine architecturally and the other is not, simply because they belong not to the same class of buildings. The stringent restrictions of Y. M. C. A. planning and design require little emphasis. Every one who has stepped into one of these buildings is familiar with the compactness of the intricate plan problem, the extremely small bed room sizes and the admission of no wasted spaces or areas. To gain adequate light and air to all these complicated appointments and rooms, and still in the exterior to obtain a related design having wall surface which bears some semblance of structural possibilities to maintain itself, is no mean problem. The Downtown Y. M. C. A. building has met these obstacles and surmounted them in an admirable manner. It is a worthy piece of architecture, and Pittsburgh may well take pride in the fact that it is hers in more ways than one.

K. R. C.

For a very brief period in the 1980s, the style known as “Postmodernism,” which perhaps we might better call the Art Deco Revival, was the ruling trend in skyscraper design. Fortunately Pittsburgh grew a bountiful crop of skyscrapers in the Postmodern decade, and here is one of the better ones. In it we see the hallmarks of postmodernism: a return to some of the streamlined classicism of the Art Deco period, along with a sensitive (and expensive) variation of materials that gives the building more texture than the standard modernist glass wall. This skyscraper is part of Liberty Center, which was begun in 1982 and finished in 1986; the architects were Burt Hill Kosar Rittelman.

CAF car no. 4322 in the subway between Gateway and Wood Street. Someone put a lot of effort into decorating it: all the interior lights were replaced with alternating red and green, all the poles and grip rods were covered with spirals of electrical tape, and stick-on Christmas decorations were all over the windows. Whoever is responsible should get a raise and a promotion. In fact, whoever is responsible should be in charge of Pittsburgh Regional Transit.