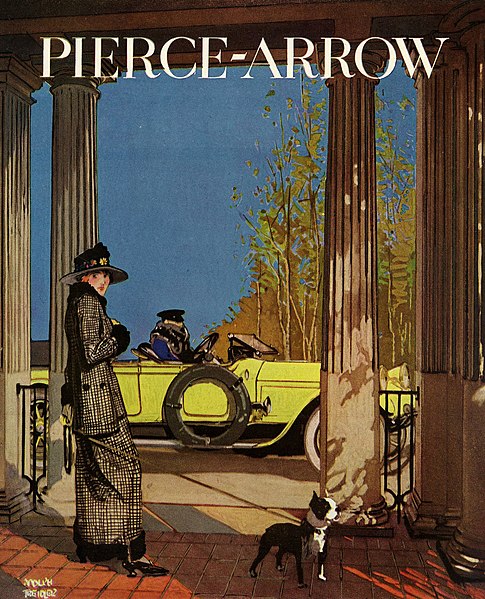

We continue our visits to car dealers of the mythic past with one that catered to the very highest class of motorist. The Painter-Dunn Company sold Pierce-Arrow cars, a luxury brand that lasted until 1938. This dealership is the architectural equivalent of the Pierce-Arrow advertisements, which concentrated on elegant design without trying to tell us how good the car was. The design conveyed the message.

Father Pitt does not know the whole history of this building. The elaborate cornice at the top of the second floor suggests that the third floor was a tastefully managed later addition.

Addendum: The Construction Record in 1915 confirms that this building was put up as two floors, and names the architects: “Architects Hunting & Davis Company, Century building, awarded to Henry Shenk Company, Century Building, the contract for constructing a two-story brick and terra cotta garage and assembly shop on Center avenue, Shadyside, for the Painter-Dunn Company. Cost $100,000.”

Note how Millvale Avenue runs right into the garage entrance.