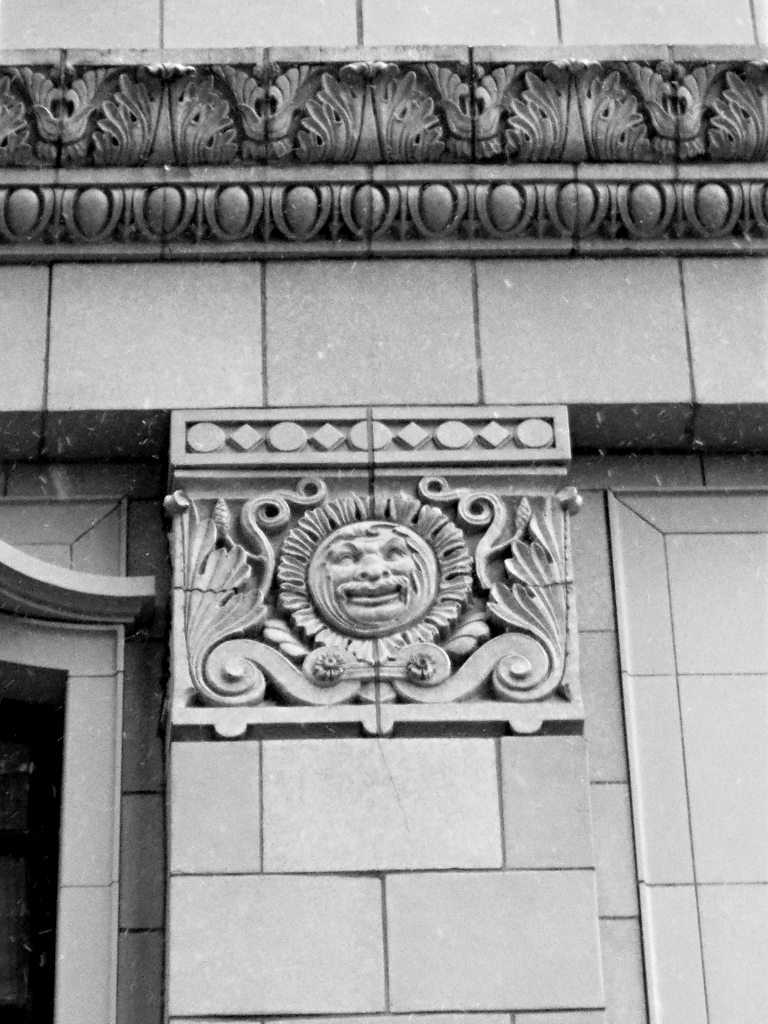

You need a sharp eye, and a long lens, to pick out some of the details on Heinz Hall from ground level. At first the exterior appears to be rather staid, but it rewards close examination with some charmingly whimsical decorations. (The white spots visible in these pictures are snowflakes.)

-

Heinz Hall Details

-

Eye Benches at Katz Plaza

-

Victory in Lawrenceville

Lawrenceville has two First World War memorials. The most famous is the Doughboy in Doughboy Square (which of course is a triangle) at the intersection of Penn Avenue and Butler Street. But this more modest memorial at the corner of Butler and 46th Street is a charming statue of Victory that would be the pride of any neighborhood that did not already possess a greater masterpiece.

-

Hall of Architecture, Carnegie Museum

This is the most breathtaking single room in the Western Hemisphere. That statement is likely to provoke some opposition, but Father Pitt is willing to defend it.

In the late nineteenth century, many museums collected plaster casts of the great monuments and sculptures of the past. The casting preserved the minutest details of the surface in three dimensions, so that a museum visitor can study every chisel mark on a famous Romanesque facade without having to hop on a steamer and travel to Europe.

In the twentieth century, the cult of originality persuaded most museum curators that these plaster casts were worthless. Almost all the great collections were broken up and thrown out. Only three of them remain in the world, and only one of them—this one—is still in the space that was built to house it, never having been shuffled from one wing to another or stored for years under a highway overpass.

Now, at last, some of the more enlightened art historians are beginning to understand the value of the casts. Here a Pittsburgher can study the whole history of Western architecture from Egypt to the Renaissance without so much as crossing the Monongahela. But even more important is the fact that these casts are more than a century old. The twentieth century, with its corrosive pollution and horrendous wars, was more destructive to ancient monuments than any other century. But here we can see exact replicas of these monuments as they were before all the corrosion and destruction. This collection is a unique cultural treasure, worth crossing a continent or an ocean to see.

-

Hall of Sculpture, Carnegie Museum

The Hall of Sculpture was built in imitation of the interior of the Parthenon, with marble from the same quarry that supplied the marble for the famous Athenian temple. It was intended to house the Carnegie’s collection of plaster casts of famous sculptures, some of which still adorn the balcony, and some of which have been moved to the Hall of Architecture. On the floor below, staff are hanging transparencies from clotheslines. Why? We’ll find out when they’re done.

-

Primitive Science, Modern Science

These bronze reliefs by Sidney Waugh stand over what was once the main entrance to the Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science (to give its full title). From loincloths to lab coats is less of a distance than you might think: Waugh took pains to illustrate the remarkable cleverness of the “primitive” American Indians who had long-distance communication (via smoke signals) and snowshoes, an invention Waugh chose specifically because it arose only in North America and nowhere else. As for Modern Science, we should not underestimate the difficulty of imparting dignity to a figure in a lab coat, a feat Waugh has carried off with aplomb. To a world used to the opposition of modern science against primitive superstition, Waugh presents the two figures as engaged in exactly the same enterprise.

-

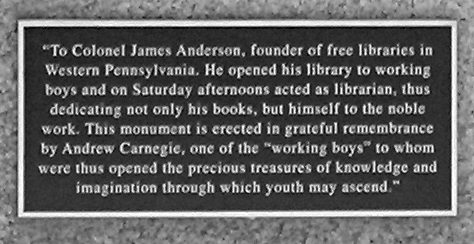

Col. James Anderson, Founder of Free Libraries

Who was the founder of free libraries in Western Pennsylvania? You might say Andrew Carnegie, but Mr. Carnegie himself will be the first to correct you. As a boy, he spent his Saturdays in the library of Colonel James Anderson, whose selfless example inspired Carnegie to become the greatest patron of libraries in the history of civilization. This monument, put up by Carnegie in 1904 near his Free Library in Allegheny, may look humble at first glance, but for the art Carnegie engaged possibly the greatest American sculptor of all time, Daniel Chester French. It still stands beside the Buhl Planetarium, just across the plaza from the old Carnegie Free Library in Allegheny Center.

The inscription is obviously more recent than the monument, but probably duplicates the wording of a lost plaque:

Allegheny Center is a short walk from the North Side subway station.

-

The Heavens and the Earth

These stunning Art Deco reliefs by Sidney Waugh decorate the old Buhl Planetarium, now part of the Children’s Museum. The Carnegie Science Center , which replaced the Buhl Planetarium as our chief science museum (and has the old Zeiss projector from the Buhl Planetarium on display), is big and exciting, but it was not built at a time when the meeting of science and art was as fruitful as it was in the Moderne era.

-

Edward Manning Bigelow

Edward Manning Bigelow was, by all accounts, as corrupt as any other Pittsburgh politician of his day. But he had two things that earn him a place in history: a vision of Pittsburgh as a great city, and a silver tongue with little old ladies. Seeing that Pittsburgh was rapidly expanding to the east, he determined that a great city must have a great park. Right in the way of the eastward expansion was Mary Schenley’s broad expanse of empty land. Mary Schenley was heiress to the O’Hara glass fortune, but she had abandoned Pittsburgh and moved to England. Bigelow went there and persuaded her to donate her land to the city. In her honor, we call it Schenley Park, and—just as Bigelow imagined it—it’s a beautiful oasis of fields, forests, and art in the middle of the city. One of those works of art is this statue of Bigelow himself, which stands in the middle of the street in front of Phipps Conservatory. Here we see it surrounded by the golden late-fall leaves of Ginkgo biloba.

-

Westinghouse Memorial (part 2)

Almost no one ventures behind the Westinghouse Memorial, but a special reward awaits those who do. Instead of a blank wall, we find reliefs as detailed as the ones in front. We can see the backs of the standing figures, and the leafy ornament that surrounds the figures and the panels turns out to arise very logically from tree trunks in the rear. Since the effect from the front would be the same if the rear were blank, there seems to be no real reason for having gone to this much trouble—except that knowing what’s behind changes our perception of the front. The front view has a kind of aesthetic truth that it would not have if the ornament did not have its logical foundation in the rear.