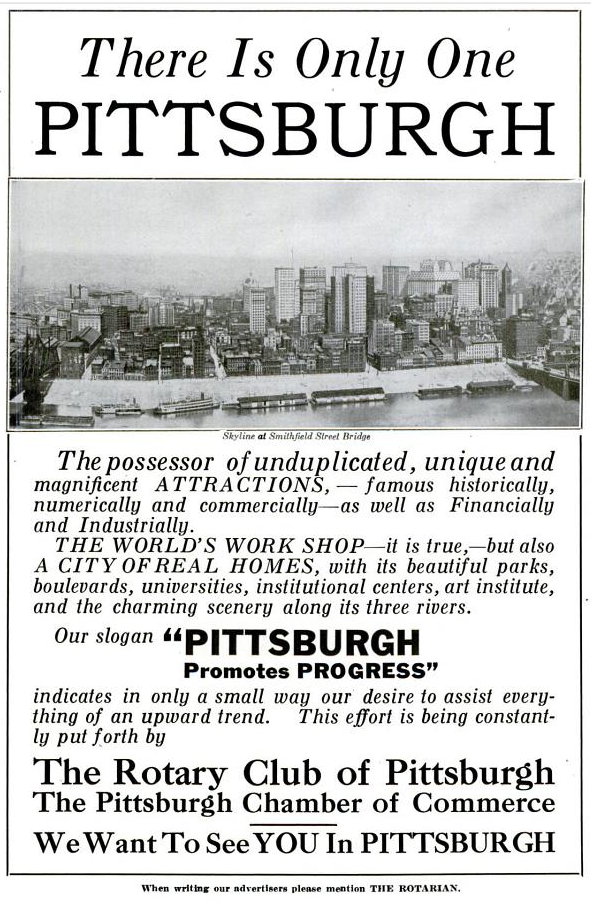

Old Pa Pitt does not have an exact date for this old postcard, but it appears to be from about 1915 or so, to judge by the buildings. In those days, Pittsburgh was one of the three great homes of the skyscraper, along with New York and Chicago.

-

Pittsburgh Skyline a Century Ago

-

St. Mary’s Church, Sharpsburg

-

Pittsburgh in 1916

-

Mary Roberts Rinehart Lived Here

The Circular Staircase was one of the greatest bestsellers of all time, and Mary Roberts Rinehart lived here when she wrote it—just half a block up Beech Avenue from the house where Gertrude Stein, a writer with a somewhat different style, was born. The success of The Circular Staircase made Mary Roberts Rinehart one of the most powerful literary figures in America, and her good business sense consolidated that power into a publishing empire for her family.

-

Thirteen Stars, Thirteen Stripes

-

“Pittsburgh,” by E. M. Sidney

-

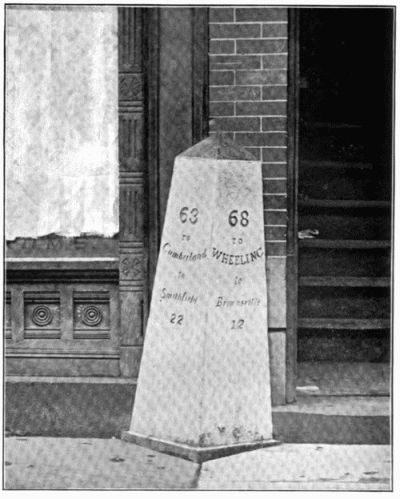

The Old Pike

A very interesting book on the subject of the National Pike has just appeared at Project Gutenberg. The National Pike (now U.S. Route 40, and for substantial stretches Maryland Route 144) brought the East to the West, and passes through what are now the southern suburbs of Pittsburgh. Many milestones of the sort seen in the photograph still exist, and are lovingly maintained.

The idea of a federally funded highway to the West was a product of the Jefferson administration; the right wing, of course, denounced it as a pinko plot. (The word for “pinko” in those days was “Jacobin.”)

The author of the book, Mr. Thomas B. Searight, was the son of the Searight who operated a tollhouse west of Uniontown. That tollhouse is still there; it is built to the standard octagonal plan of the tollhouses on the National Pike.

The Old Pike. A History of the National Road, with Incidents, Accidents, and Anecdotes Thereon. Illustrated. By Thomas B. Searight. Uniontown, Pa: Published by the Author. 1894.

-

Pittsburgh Businesses in 1819

Pittsburgh was already a thriving small city nearly two hundred years ago, as we can see from a directory to the city published in 1819. A few of the advertisements from the back of the book give us a good picture of the commercial landscape of the place.

Taverns were common, of course, and what traveler would not be reassured by the name of this one?

We are almost certainly meant to read this as “Spread Eagle Tavern.” Rebuses were common in advertisements throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. Note the address, by the way. There were no address numbers in the Pittsburgh of 1819; advertisers had to give explicit directions relative to notable landmarks.

We have forgotten in our days of central heating how important a good bellows used to be.

As Pittsburgh grew more prosperous, homeowners kept up with the latest fashions. One popular fashion was to have mural wallpapers installed in the largest rooms of the house, and Pittsburgh was apparently not only a consumer but also a supplier of such decorations.”Third street,” by the way, is what we now call “Third Avenue.” Our numbered “avenues” were called “streets” in those simpler days; the numbered “streets” on our current map had individual names in 1819.

Of course, the reason Pittsburgh existed in the first place was because the site controlled the access to the West by way of the Ohio River, and much of the business here catered to travelers embarking for the new countries to the west. Grocers like Mr. Cotter kept everything you would need to stock your boat for a long trip.

-

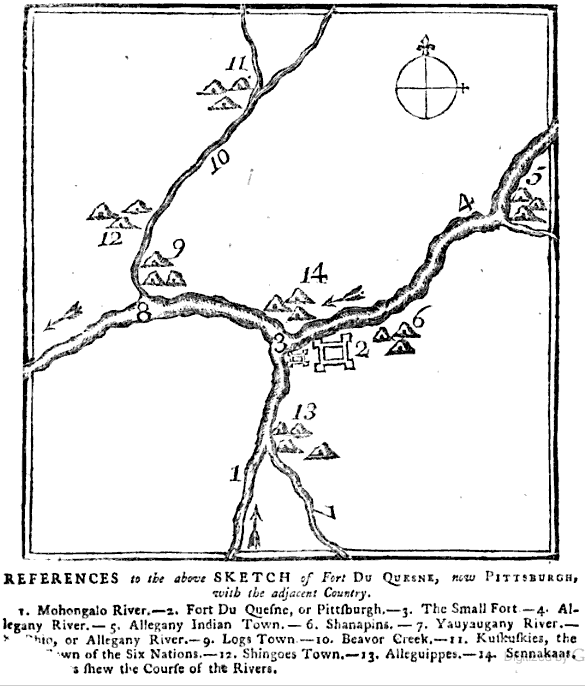

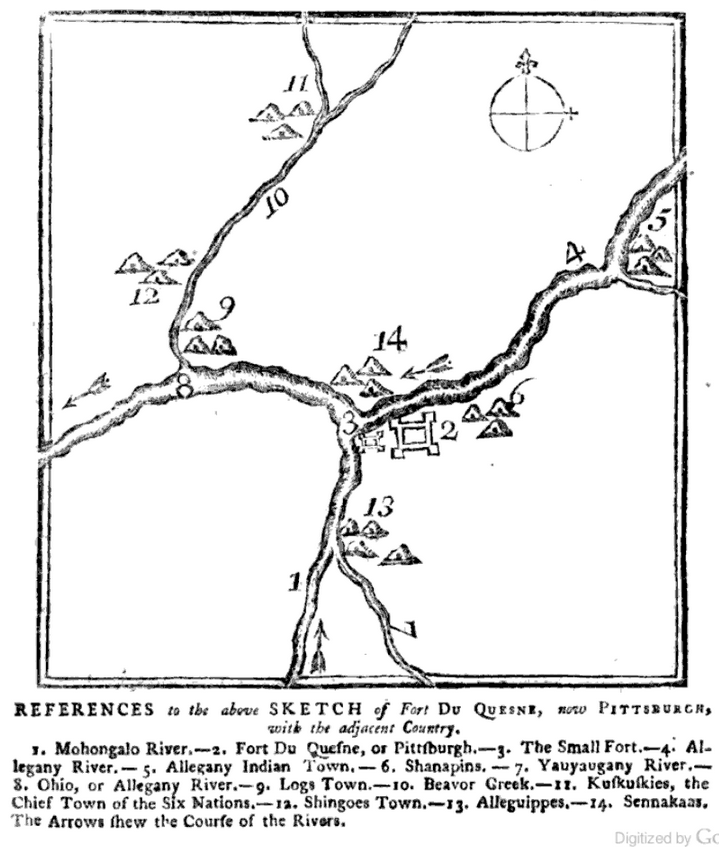

Very Early Map of Pittsburgh, 1759

UPDATE: Another more intact copy of the map has surfaced; see below.

Old Pa Pitt is very pleased to be able to present to you what must be one of the very earliest printed maps of Pittsburgh, perhaps the very earliest, printed only a month or so after the British founded the place on the ruins of Fort Duquesne. It can be found on the last page of the London Magazine: or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, for January of 1759. Unfortunately a bit of the page is torn, but the missing words do not affect the meaning very much. (The last line almost certainly reads, “The Arrows shew the Course of the Rivers.”) All friends of civilization owe a great debt of gratitude to the Google Books project for making possible research that would have taken decades of work and thousands of miles of travel in the old days of, say, ten years ago.

——Father Pitt has found another copy of the same magazine in which the page is not torn. Here is the same map intact:

-

Point Park: An Error Corrected

The Pittsburghers have committed an error in not rescuing from the service of Mammon, a triangle of thirty or forty acres at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela, and devoting it to the purposes of recreation. It is an unparalleled position for a park in which to ride or walk or sit. Bounded on the right by the clear and rapid Allegheny rushing from New York, and on the left by the deep and slow Monongahela flowing majestically from Virginia, having in front the beginning of the great Ohio, bearing on its broad bosom the traffic of an empire, it is a spot worthy of being rescued from the ceaseless din of the steam engine, and the lurid flames and dingy smoke of the coal furnace. But alas! the sacra fames auri is rapidly covering this area with private edifices; and in a few short years it is probable, that the antiquary will be unable to discover a vestige of those celebrated military works, with which French and British ambition, in by-gone ages, had crowned this important and interesting point.

——A Pleasant Peregrination through the Prettiest Parts of Pennsylvania, performed by Peregrine Prolix.

Our author looked down on Pittsburgh in 1835 and recommended a park exactly the size (“thirty or forty acres”) of Point State Park (which is 36 acres). Seldom in the history of urban planning has a need for green space in a particular location been so obvious; certainly it is even more seldom that the crying need is actually met by enlightened urban planners, even if it took us till 1974.