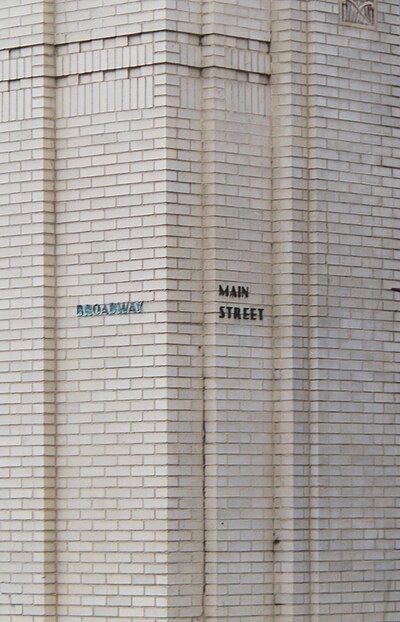

The Masonic Hall in Carnegie is a fine example of small-town Rundbogenstil, taking its details from Renaissance architecture and its rhythm from industrial Romanesque.

If Father Pitt owned this building and had to put up with those two modern blisters on top, he would have them painted to look like cat ears.

The goat ornaments were doubtless intended to reassure the Masons’ neighbors that Masonry has no satanic connotations at all.