The Allegheny County Courthouse was finished in 1886, its tower the tallest thing in the city. In 1902, the Frick Building went up across the street, facing down the courthouse and blocking the view of the tower from much of the Golden Triangle.

Mr. Franklin Toker (Pittsburgh: An Urban Portrait, p. 70) tells us that the Frick Building was part of what may be the most extravagant display of architectural pettiness ever contemplated. Henry Frick had fallen out with his old patron Andrew Carnegie, and he considered the breach irreparable. The Carnegie Building was one of the finest office buildings in the city; Frick surrounded it with taller buildings that blocked out its views, light, and air, symbolically suffocating Mr. Carnegie (who had removed to Scotland and was therefore out of reach of literal suffocation). The Carnegie Building is gone, replaced with a singularly windowless annex to Kaufmann’s (now Macy’s); Frick’s monumental wall around it remains.

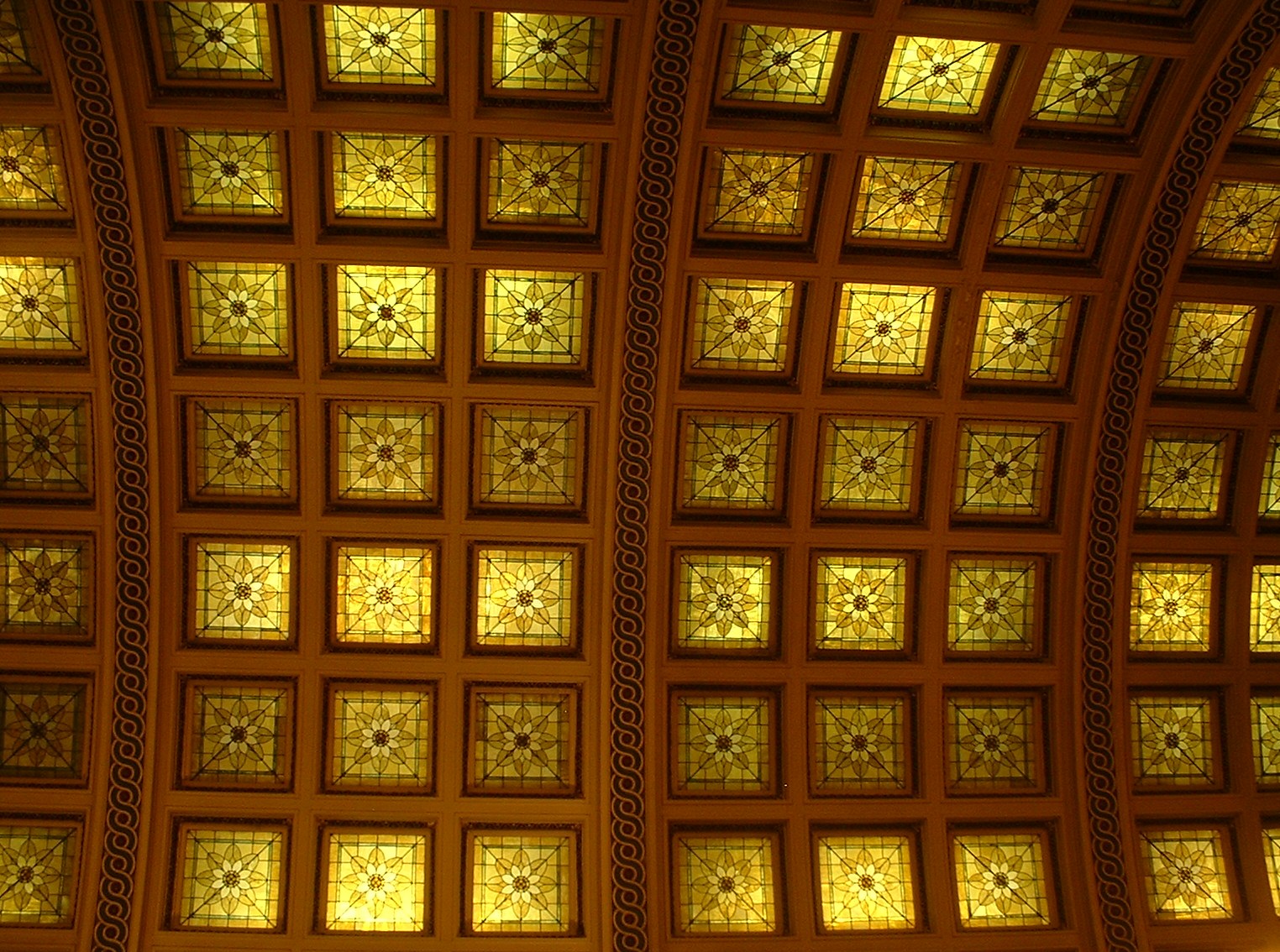

That story aside, the Frick Building is an exceptionally fine piece of architecture. Daniel Burnham designed it, and its classical elegance must have pleased Frick immensely. It has the misfortune, however, of being right across the street from “the best building in America,” as Philip Johnson famously called Richardson’s courthouse. Not even Daniel Burnham could compete with Richardson’s masterpiece, and wisely he decided not to. Burnham’s Pennsylvania Station is an extravagant spectacle; this is simply a remarkably tasteful office building, in its way nearly perfect.