If you need something ghastly for Halloween, here is a ghastly white pumpkin still on the vine, from Father Pitt’s own pumpkin patch.

If you need something ghastly for Halloween, here is a ghastly white pumpkin still on the vine, from Father Pitt’s own pumpkin patch.

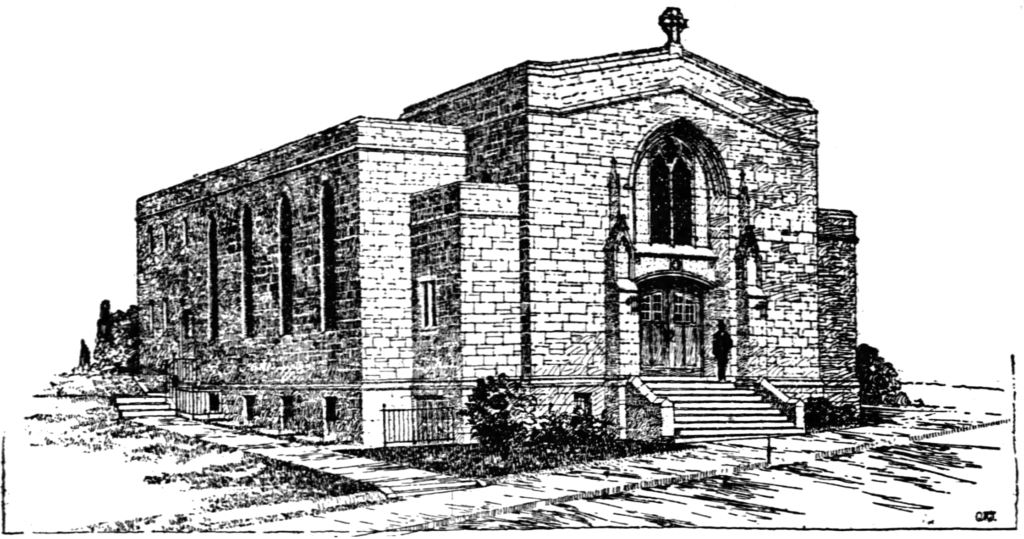

In honor of Reformation Day, here is a Lutheran church. O. M. Topp, for a generation the favorite choice of Lutherans, designed this neat Gothic church, which was built in 1929, as we see from the cornerstone.1 But, oddly, the cornerstone says that the church is the Sunday school.

That’s because things didn’t go exactly as planned. This was meant to become the Sunday-school wing, temporarily serving as the sanctuary until the much larger church was built. But then the Depression came, and then the war, and the big church was never built. Instead, when the congregation was finally ready to expand in 1960, it was decided to keep this building as the sanctuary, and a large modern Sunday-school wing was built beside it.

The architect’s drawing shows us that nothing on the outside has changed except for the encrustation of newer building to the left.

The Sunday-school wing is in a very different style, but tall Gothic arches are meant to tie it to the earlier building.

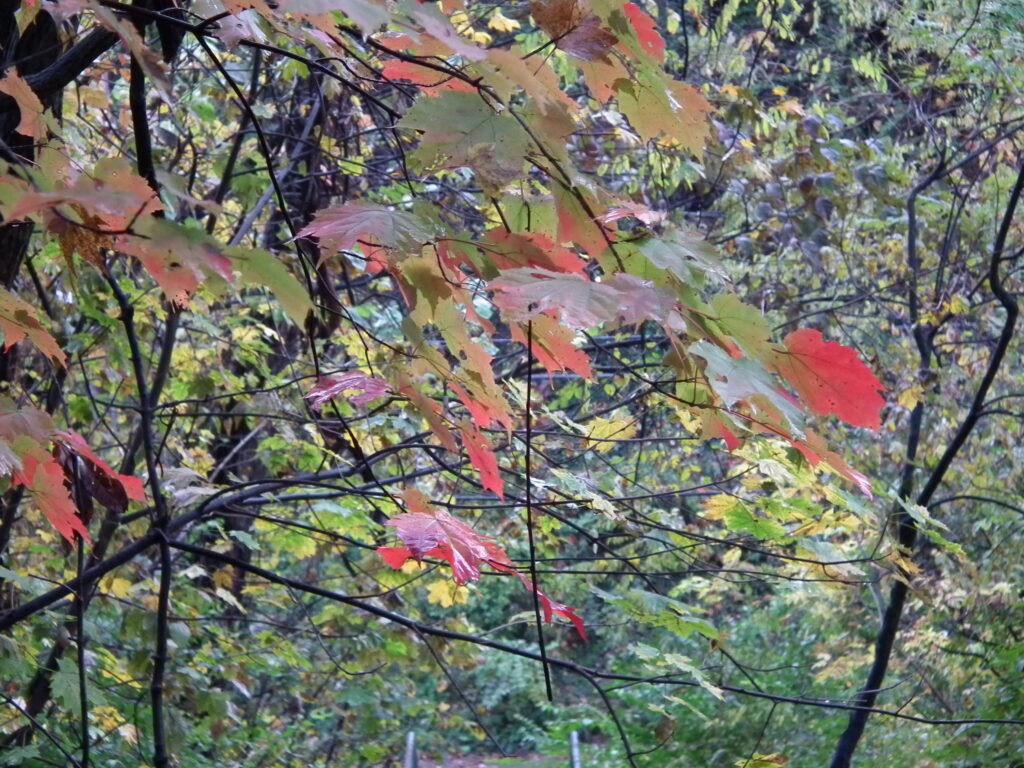

Father Pitt usually thinks of the photograph as the raw material for a picture, meaning that the photograph will go through a good bit of adjustment before he publishes it. But every once in a while, he challenges himself to publish pictures directly from the camera. On this expedition, he also focused all the pictures manually, just to see how good the Fujifilm FinePix HS10 was at manual focusing. Pretty good.

One of several “flatiron” buildings produced by the irregular street layout of Crafton. This one is odd angles all around.

The main entrance is on the sharp corner facing the intersection of Noble Avenue, Crafton Avenue, and Dinsmore Avenue (which is what we meant when we said Crafton had an irregular street layout).

A segmental pediment—that is, a pediment whose top is a segment of a circle, rather than the more usual triangle.

The side entrance would have led into the upstairs offices: a bank putting up a building like this would expect to make extra income from office rentals, and bank buildings were usually prestigious addresses.

The side of the building not meant to be seen is finished more cheaply.

This church was built in 1927, but it is very similar to churches built half a century before that. Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists enthusiastically adopted the Akron Plan at the turn of the twentieth century, building square auditorium-style churches, often with big corner towers. The auditorium plan made sense in a church where the emphasis was on preaching. Lutherans, Catholics, and Episcopalians stuck to the traditional center-aisle church plan, because their emphasis was on liturgy.

The architect was John A. Long,1 who by this time was one of the old reliables in Pittsburgh. The church is no longer Lutheran, but it is neatly kept by the current occupants, the Agapé Life Church.

An unusually well-preserved small foursquare house that is charming and handsome in its way, in spite of being an architectural muddle. If you try to judge it by any standard of symmetry or proportion, you will quickly conclude that nothing is in the right place. But even after those thoughts have run through your mind, you are likely to think that somehow, in defiance of all correctness, it is a good-looking house.

The lantern of Hamerschlag Hall seen across the rooftops from the other end of Oakland.

A tidy four-unit building fitting a lot of living space into a small lot. The style is very simple, but little details—the suggestion of battlements in the roofline, rectangles and a diamond of terra cotta—give what would otherwise be a prosaic building some romantic appeal. It’s about time for the awning man to come by and take those awnings down for their winter cleaning.

After months of work, the Hollywood, Dormont’s century-old neighborhood movie palace, is open again as the Row House Hollywood, showing an eclectic mixture of classic movies, cult films, and independent productions. As a rare undivided big-screen theater, the Hollywood is big enough to accommodate special performances, like a showing of Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc with the Bach Choir of Pittsburgh.

Charles R. Geisler designed the original 1925 building (the Spanish Mission details are certainly his); Victor A. Rigaumont, Pittsburgh’s titan of Deco theaters, supervised a remodeling in 1948.

The Hollywood is an easy stroll from the Potomac station on the Red Line. There are also public parking lots nearby for the carbound, but isn’t half the fun of visiting a silent-era movie palace using a period-appropriate transit line to get there?