“My heart is in the work,” said Andrew Carnegie in 1900, and it was a good enough slogan to be immortalized in glass, especially if Carnegie himself was paying for it.

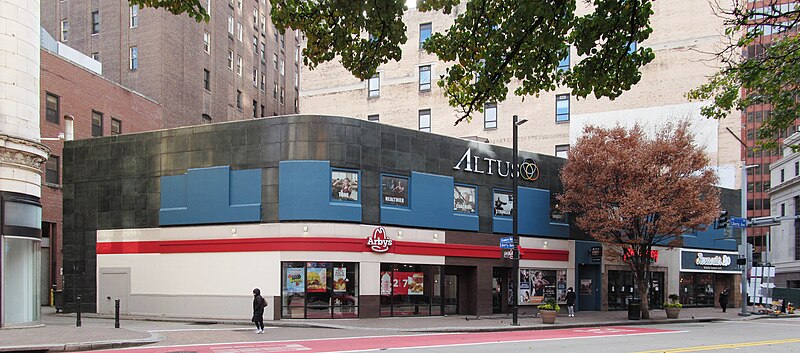

The Liberty Avenue face of this building has been modernized and remodernized so many times that no one would take it for anything remarkably old. But it is actually one of the very few commercial buildings remaining downtown from the Civil War era. It was built in about 1865 for Arbuckle & Company, a dealer in coffee and sugar in the days when Liberty Avenue was the wholesale food district, with a railroad running right down the middle to bring the food in at its freshest. And if you will come around the back with us, you will see one of Pittsburgh’s odd little hidden treasures.

The short alley behind the building is still called Coffey Way, and the back of the Arbuckle building shows the very old bricks we might expect. And among those bricks, in an alley that hardly anyone even knows about, we find “some of the oldest surviving architectural sculpture in the city,” according to Discovering Pittsburgh’s Sculpture by Marilyn Evert.

These medallions are obviously meant to represent specific figures, but no one is quite sure which specific figures. This one has been identified as George Washington or Colonel Bouquet (the one who built the blockhouse).

This keen-eyed lady has been identified as Jane Grey Swisshelm or Mary Croghan Schenley.

This is probably an allegorical head of Liberty, although it has also been identified as an “Indian head” of the sort common on nineteenth-century coins.

This one is very likely to be Abraham Lincoln, but “very likely” is the most certainty we can summon up. It could also be John Arbuckle himself, the head of the firm, who appears in a later photograph with a beard and distinctively hollow cheeks. We note that this is the only one of the faces turned left instead of right; if you like to find symbolism in things like that, go ahead.

John Arbuckle, incidentally, was the inventor of processes for preserving coffee and automating its packaging, so we may regard him as the founder of coffee as a mass-produced consumer product. This little alley, therefore, ought to be on every coffee-lover’s pilgrimage list.

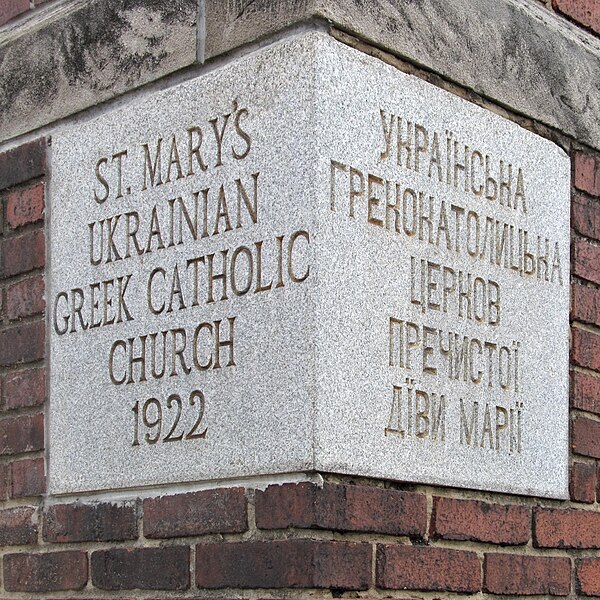

Now St. Mary Ukrainian Orthodox Parish. The history of Catholic and Orthodox Ukrainian Christians in the United States is complicated, and old Pa Pitt will not attempt to sort it out here. It ends with double Ukrainian churches in many neighborhoods, and that is the case here: there is a more recent Ukrainian Catholic church around the corner from this one.

This impressive building was designed by Carlton Strong (whose full name was Thomas Willet Carlton Strong, and no wonder he usually shaved off half of it). Strong’s most famous work was the magnificently Gothic Sacred Heart in Shadyside, but he adapts very well to the Byzantine style here and gives the Bottoms a distinctive addition to its skyline.

The rectory is in a different style; it is certainly one of the most splendid houses in the Bottoms.

The fence behind the rectory has recently been repainted in a patriotic color scheme.

Carlton Strong, incidentally, came to Pittsburgh as a designer of apartment buildings, giving us the Bellefield Dwellings as his first work here. He later converted to the Catholic faith and became one of our most prominent church architects. You can read a good biography of Carlton Strong by the distinguished local historian Kathleen M. Washy on line:

Built in 1960, this church adopted a radically simplified Byzantine architecture. It is much smaller than its Ukrainian Orthodox (formerly Ukrainian Greek Catholic) neighbor St. Mary’s around the corner, but both congregations continue to inhabit the same neighborhood without throwing bricks at each other.

The attached rectory is in an equally simple style; the pasted-on false shutters are an attempt to make it feel less institutional.

Now billing itself as just an “Orthodox” church, since the Russian Orthodox church in America became autocephalous in 1970 and has long included a broad spectrum of ethnicities. This church was built in 1914, and the architect was George W. King—a name that so far does not appear anywhere else on old Pa Pitt’s Great Big List of Buildings and Architects. “King” does not sound like a particularly Russian name, though Ellis Island could do funny things to people’s names. But he certainly seems to have captured the spirit of Russian church design, and these onion domes are one of the most distinctive features of the skyline of the Bottoms.

After the baroque elaboration of the church, the rectory seems almost ruthlessly plain. But it does its job well: it matches the church in materials, thus showing its association, but it directs all attention away from itself and toward the church, which seems theologically appropriate.

Charles W. Bier was a fairly successful Pittsburgh architect, especially busy with medium-sized churches, who flirted with Art Nouveau in the days before the First World War, but retreated into a more traditional style in the 1920s (see, for example, his 1923 Mount Lebanon Methodist Episcopal Church). Here we find him at his most radically modern in a line of three identical double duplexes, built in about 1915 or 1916.1

These broad entrance arches with strong vertical lines show up on Mr. Bier’s churches of the period as well.

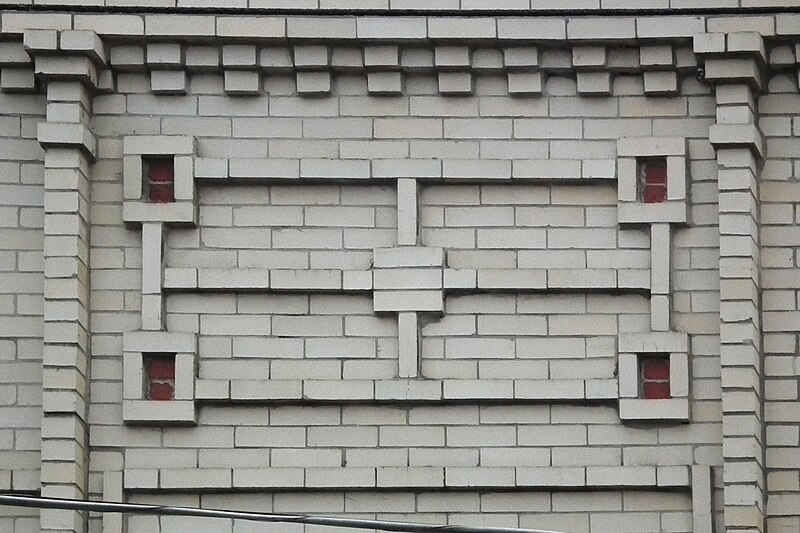

The geometrical brickwork ornaments remind us of the decorations in German art and architecture magazines of the period, and they may be where our architect got his ideas. (According to Martin Aurand, Frederick Scheibler took much inspiration from those German magazines, so they were available here.)

The building at the right end of the row seems to be stuck in the middle of a refurbishing project, with new windows installed and new wood framing inside. We hope the work can continue, because these three striking buildings really are unusual in Pittsburgh and ought to be preserved.

By most standards the SouthSide Works, by far the largest “new urban” development in Pittsburgh, has been a great success. The retail part of it, however, has had its ups and downs. It was planned with a focus on a “town square” a block away from Carson Street, with 27th Street as a line of shops linking Carson Street to the center of the new neighborhood, and then rows of smaller shops here along Carson Street, the back side of the development. What happened might have been predicted by a good urban planner: the part of the development that continued the well-established Carson Street business district flourished and remained mostly occupied, spilling its prosperity across the street to previously empty storefronts and triggering new construction; meanwhile, the “town square,” after an initial burst of success, languished, with many large storefronts empty. Now the square has filled up again, and we shall see where the cycle takes us from here.

Architecturally, the Carson Street side of the development is again a success. It may not be inspired architecture, but it does its job of fitting with the established architectural traditions of the South Side and visually connecting itself with the rest of the Carson Street business district. Father Pitt might point out, however, that some of the materials—metal facings of buildings, for example—are beginning to look a bit bedraggled already. The parts faced in brick, however, are not. This may serve as a lesson to young architects: brick lasts.

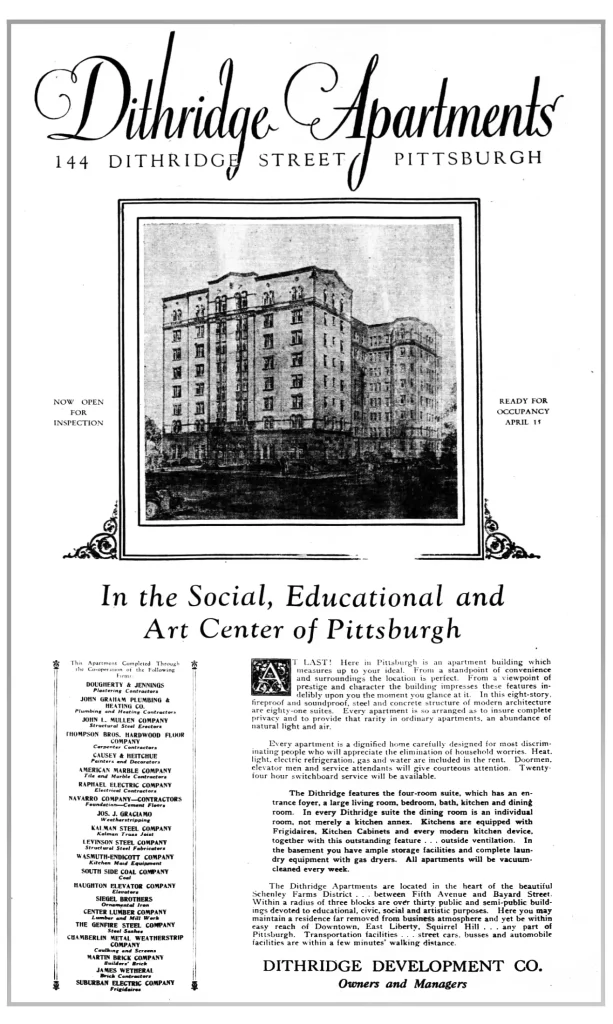

Built in 1929, this eight-storey apartment tower has a newer ninth floor sheathed in what appears to be corrugated metal. Father Pitt has some advice for architects contemplating asymmetrical additions with cheap materials to symmetrical Renaissance palaces like this:

Like several other apartment buildings in the area, this one is festooned with grotesque whimsies.

The rear section has a bay rising the entire height of the building, with a corrugated-metal hat on top.

Addendum: A kind correspondent has found an advertisement for the Dithridge Apartments when they were new, which supplies us with a definite date (1929; they were to be ready for occupancy in April) and shows us the building as it looked before the top was altered.

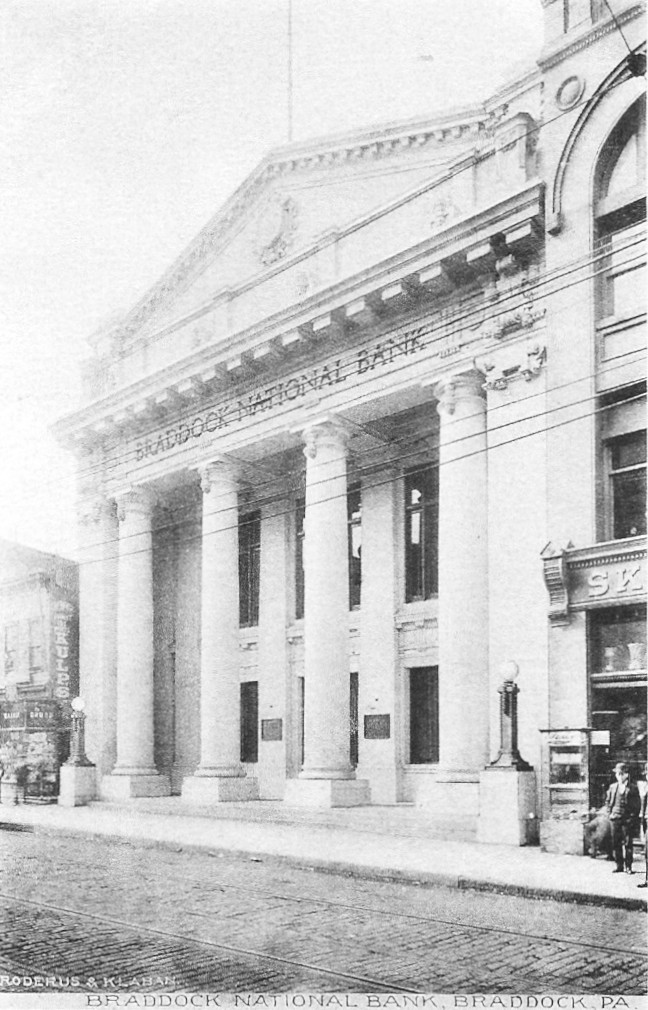

This splendid edifice cost about $100,000 when it was built in about 1905. The architects were McCollum & Dowler,1 and that Dowler is the young Press C. Dowler, who would practice architecture for two-thirds of a century and run through every style of his long lifetime, from Romanesque through Art Deco to uncompromising modernism. The building still stands today on Braddock Avenue, and the front still looks about the same.