The ground-floor storefront was replaced at some time in the modernist era, but the upper two floors preserve two-thirds of a fine terra-cotta front.

Comments

The ground-floor storefront was replaced at some time in the modernist era, but the upper two floors preserve two-thirds of a fine terra-cotta front.

The front of green terra cotta is unique in Pittsburgh. Frederick C. Sauer designed this building, and when it was done he moved his office into it. It is the only one of Sauer’s buildings, as far as old Pa Pitt knows, that bore his name on the building itself, though at some point some workman, doubtless thinking he was doing a splendid job of renovating the building, did his best to obliterate the letters:

Addendum: As we might have guessed from looking at the front, the building rose in two stages. Three floors were added in 1909.1

S. S. Kresge was never the presence in Pittsburgh that Murphy’s was, but all the five-and-dime stores had outlets downtown. Murphy’s, Kresge’s, McCrory’s, Woolworth’s—they were all similar operations, and all the founders knew each other. G. C. Murphy, in fact, had worked for S. S. Kresge and John G. McCrory before setting out on his own.

The S. S. Kresge Company is better known to younger people (meaning under the age of seventy or so) as the parent corporation of Kmart.

The whole front of the building is done in terra cotta, including this inscription.

The pediment, though it seems undersized for the building, is filled with rich decoration.

The giant Kaufmann’s department store grew in stages over decades. This part of it was designed by Charles Bickel, who decorated it with exceptionally fine terra-cotta ornaments.

Doubtless built for very pedestrian commercial uses—with huge windows that provided bright light from the south all day—these two buildings nevertheless could not be seen in public until they were dressed in the proper Beaux-Arts fashion. Other more recent buildings grew up around them and then were torn down, but these have survived, and seemed to be getting some work when Father Pitt walked past them recently.

Both buildings pull from the same repertory of classical ornaments in terra cotta, but mix them up in different ways.

No. 819 is more heavily ornamented—both in the sense of the abundance of ornaments and in the sense that the individual ornaments seem weightier:

No. 821, on the other hand, is decorated with a lighter and more Baroque touch:

This beautiful building shows some obvious influence from Henry Hornbostel’s famous Rodef Shalom, but it is original enough to be called a tribute rather than an imitation. The architects were Charles J. and Chris Rieger, and it is a backhanded compliment to these underappreciated brothers that some of their best works have been misattributed to more famous architects. This building in particular is usually attributed to Alexander Sharove, but we are quite sure that the Riegers designed it.1 The cornerstone was laid in 1928, and the building was dedicated in September of 1929.

The entrance, which is where the Hornbostel influence is most obvious, is a feast of polychrome terra cotta and stained glass.

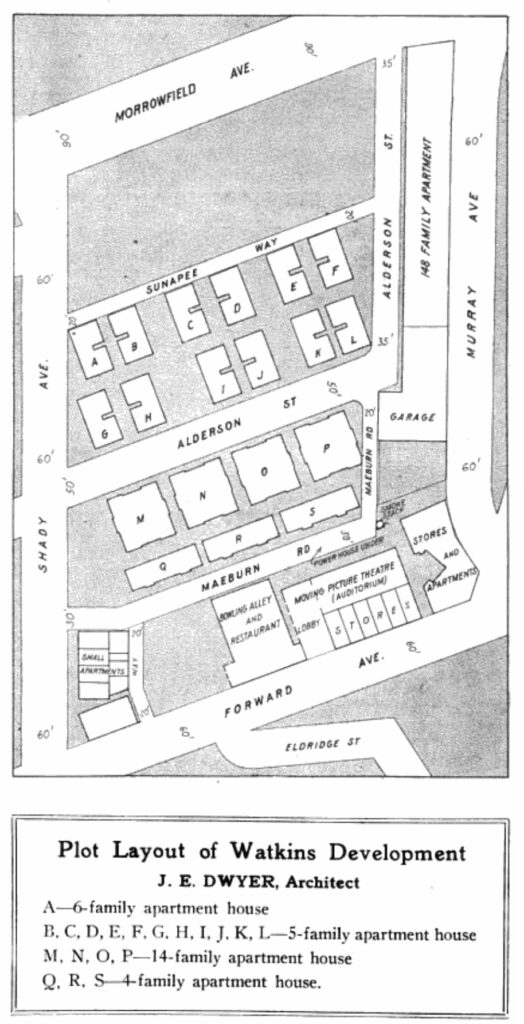

The Morrowfield is that big building that looms ahead as you approach the Squirrel Hill Tunnel on the Parkway from downtown Pittsburgh. It was built in 1924 as part of a huge development promoted by developer Thomas Watkins as “a city set on a hill,” and most of the buildings—including this one—were designed by the architect J. E. Dwyer, originally from Ellicott City, who built himself a house right next to the site and spent years supervising construction projects.

In this map from “A City That Is Set on a Hill,” Building Age, December, 1923, p. 36, the big rectangle marked “148 FAMILY APARTMENT” would become the Morrowfield.

The same article printed the architect’s elevation of the new apartment building, spread across two pages. We have taken some pains to restore it to legibility.

The building went up at a breakneck pace, with crews doing everything all at once. It was finished in less than a year. Below, “Steel work in the early stages showing the brick filler walls being laid before the concrete work was begun, to rush the job along.”

By the time the October, 1924, issue of Building Age came out (from which the pictures of the construction above were taken), the whole project was complete, and this photograph of the building from a distance was taken in time to make it into the magazine.

The entrance is liberally decorated with polychrome terra cotta.

The building of this project was watched nationally, because it was unusual to place such a large building on such a difficult lot. The architect’s elevation shows the slope of Murray Avenue along the front; here we can see that Morrowfield Avenue, on the right-hand side (in terms of the elevation), slopes upward even more dramatically. Then the street behind, Alderson Street, slopes upward again, so that the ground-floor entrances on Alderson Street are three floors up from the main entrance on Murray Avenue.

From that same article in Building Age:

The Morrowfield Apartments presents an interesting study in the effective utilization of exceptional grades. The front elevation faces a western street that is 30 feet lower than the street level in the rear, and a grade running north and south affects the building lengthwise as well as in depth.

The consequence is that the apartment is partly seven and partly eight stories high in front, and only five stories in the rear. What is really the fourth story when seen from the south elevation, is the first when seen from the rear, and the occupants of the fourth story front are therefore enabled to reach their apartments without the use of stairs or elevator by simply coming in the other street.

A century ago, if we read our old maps right, this building was a garage—and probably warehouse—for the Pennsylvania Motor Sales Corp. (Addendum: It was built in 1919, probably finished in 1920; the architect was Thomas Hannah.1) The ground floor now houses a large Asian market full of delicious things; the upper floors still seem to be used for storage. The original windows are still in the upper floors, making this an unusually well-preserved example of commercial architecture of the First World War period.

The utilitarian square front (whose proportions are already dignified) is livened up by brightly colored tile decorations.

The history of the Horne’s building is a complicated one. The original building was one of the last works of William S. Fraser, one of the most prominent Pittsburgh architects of the second half of the nineteenth century. Only a few years after it opened, a huge fire burned out much of the interior. Some of the original remained, but, since Fraser had died, Horne’s brought in Peabody & Stearns, a Boston firm that also had an office in Pittsburgh, to design the 1897 reconstruction. Another fire hit the building in 1900, but most of it was saved. You can see a thorough report on the fire, with pictures, at The Brickbuilder for May, 1900.

In 1922, a large expansion was added to the building along the Stanwix Street side, with the style carefully matched to the 1897 original. The new building was taller by one floor, but all the details were the same, including the ornate terra-cotta cornice.

The Horne’s clock, a later addition, is not as famous as the Kaufmann’s clock, but it served the same purpose as a meeting place for shoppers. It is once again keeping the correct time.

The Keenan Building, designed by Thomas Hannah for the Colonel Keenan who had built the Press into the city’s leading newspaper, was elaborately decorated. Although the shaft was modernized somewhat half a century ago, most of the decorations remain, and among them we find portraits in terra cotta of people who were considered important to Pittsburgh when the building was erected in 1907.

William Penn, the Proprietor, who gave Pennsylvania a republican form of government.

William Pitt, friend of the Colonies, for whom Pittsburgh was named.

George Washington, Father of His Country.

Stephen Foster, at the time Pittsburgh’s most famous composer.

Mary Schenley, who owned half the city and donated Schenley Park.

Andrew Carnegie, who was a big deal.

Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States.

Edwin Stuart, Governor of Pennsylvania.

George Guthrie, Mayor of Pittsburgh.

There are faces on the second floor as well, but they are identical decorative faces.