Officially the Andrew Carnegie Free Library, or the Carnegie Free Library by the inscription over the door, but the name “Carnegie Carnegie” is obvious and irresistible and adopted for the library’s Web site.

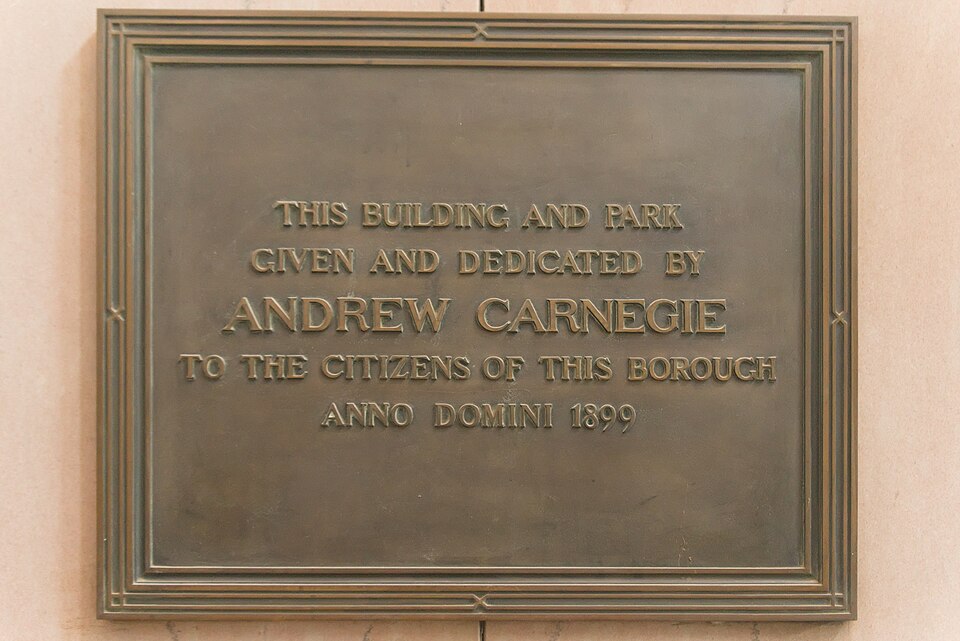

When the two Chartiers Valley boroughs of Mansfield and Chartiers merged in 1894, they decided to name the new town Carnegie after what was probably the most familiar name in the Pittsburgh area. In return, Andrew Carnegie gave them the jaw-dropping sum of $200,000 for this magnificent building (designed by Struthers & Hannah), plus money for books and—unusually for Carnegie—an endowment. His usual agreement with towns that took a library from him was that the town must undertake the upkeep, thus making the citizens ultimately responsible for their library; but in a few steel towns (where we suppose he felt more personally responsible) he endowed the library with enough of a fund to keep it going indefinitely.

Like Carnegie’s other steel-town libraries, this one was not just a library. It also had a music hall, a gymnasium, and a lecture hall.

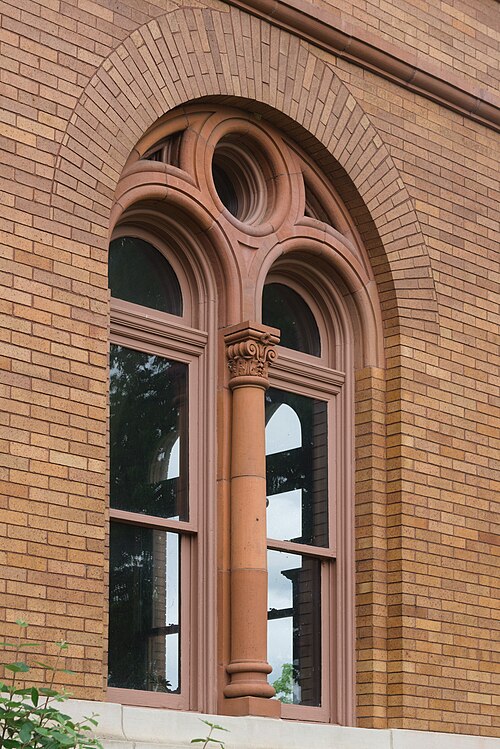

Note the terra-cotta lyre over this window on the music-hall front of the building. Today the music hall is still delighting audiences, and the library sticks to its mission of being a welcoming place to go read a book.

Columns of the Composite order, the most elaborate of the five classical orders, send the message that this is not just a library but a palace for the people.

The lobby lets us know that we have entered a building of unusual richness. Marble panels cover the walls, and mosaic tile decorates the floor.

The Greek-key pattern in the tile is repeated in the risers in the stairs.

On the second floor of the building is an extraordinarily well-preserved post of the Grand Army of the Republic, and Father Pitt will try to return soon for some pictures of the room.

The interior of the library itself mimics the experience of being a rich man with a big library—like old Col. Anderson, whose library was Carnegie’s model. You walked in, sat in front of a big fireplace, and had servants bring you books, and for an hour or two you were just as wealthy as Carnegie himself.

Open stacks have eliminated the servants, but the fireplace is still there, with a familiar face over the mantel.

In days of gaslights and low-wattage early electric bulbs, natural light from outside was still important for a reading room. Fortunately no one ever had the money to block up these windows.

All the windows are surrounded with elaborate terra-cotta decorations.

Comments