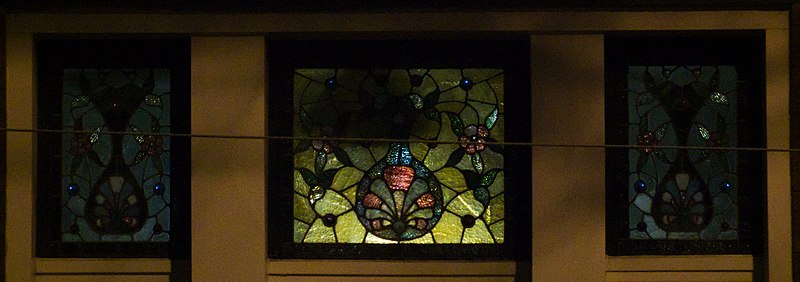

A window by Louis Comfort Tiffany, donated to the Pennsylvania Female College (now Chatham) in 1888. The figure is taken from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling: the Erythraean Sibyl, “here transformed into a symbol for women’s education,” as a plaque nearby says. This was an early work of Tiffany’s, believed to be his earliest in the Pittsburgh area. It was put away in about 1930 and sat in storage for seventy years, because who needed a window by Tiffany? In 2000 it was finally brought out of storage—old Pa Pitt imagines a janitor starting the ball rolling by saying, “Hey, can we get this thing out of the way?”—and restored for a place in the science building.

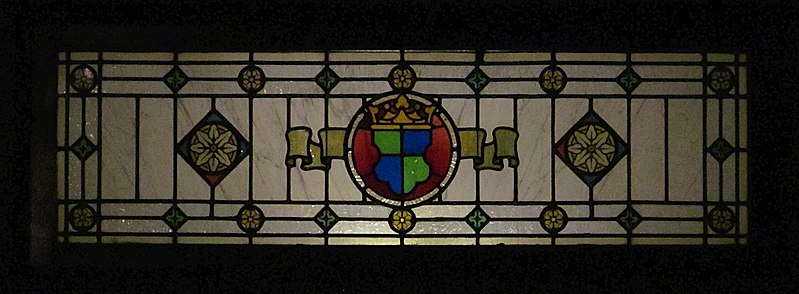

Note that Shakespeare’s name appears twice in the pantheon of great figures every young lady should know. No one else gets that honor, and—though Shakespeare certainly is worth twice as much as any of the others to an English-speaking college student—one wonders who specified the duplication, or even whether it was intentional.