The Alla Famiglia restaurant was one of the pioneers in the ongoing revitalization of Allentown, and its owners have spiffed up this building beautifully. They have also expanded into the old movie theater next door.

Comments

The Alla Famiglia restaurant was one of the pioneers in the ongoing revitalization of Allentown, and its owners have spiffed up this building beautifully. They have also expanded into the old movie theater next door.

The dense Highland Avenue business district in Shadyside spilled across the tracks from East Liberty in the 1920s. Before that, the area was a residential section that began to build up in the 1870s. And if you peer behind the storefronts, you can see that much of that residential section is still there behind a crust of commercial development. For example, the building above looks like a typical 1920s store-and-apartments building from the front, but from this angle we can see that it’s an addition to a large double house built in the Second Empire style in the 1870s.

This house had its ground floor turned into a store without extreme alterations to the rest of the building.

This Second Empire house, built in the 1880s, has a magnetic attraction for architectural debris.

The business strip along Walnut Street developed fairly late in the history of Shadyside; much of it was still residential a century ago. If we raise our eyes above ground-floor level, we can see that these little shops are built around a much older house, dating from the 1880s to judge by old maps.

A few blocks eastward on Walnut Street we find a different kind of conversion.

Here is a Second Empire mansion, built in the 1870s, converted to an apartment building, probably in the 1920s. The stucco addition on the front, with its cartoonish half-timbering that looks like a ten-year-old’s idea of Tudor architecture, fits better than it deserves to with the original house thanks to the simple expedient of painting everything white and matching the trim color.

Some day these houses will disappear. They are typical of middle-class houses that sprouted on the Hill in the 1890s, making use of the Second Empire mansard roof to give these narrow houses two more bedrooms on the third floors. Generations of condemnation notices have been pasted on them. They would be worth restoring if they were moved to another neighborhood, and perhaps they have some hope here, now that the Hill is growing new construction and looking more hopeful. But it isn’t likely that they’ll win their race with the wrecking ball.

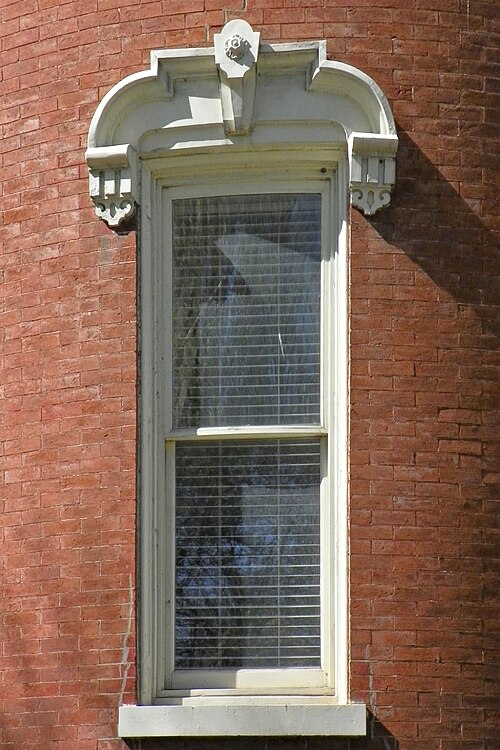

These two houses facing West Park on what used to be Irwin Avenue both have interestingly complex histories. The one above has a detailed history by the late Carol Peterson, so here we will only mention the things that led to its appearance today and encourage you to see the Peterson history for more details. It was built in about 1870 as an Italianate house. In 1890 Augusta and Jacob Kaufmann of the Kaufmann Brothers department store bought the house. It was given a third floor, and the whole house was made over in the Romanesque style with Queen Anne overtones.

The house next door was probably built at about the same time as its neighbor. Without the help of Carol Peterson, we can only report what we observe. It was also built in the Italianate style, and it looks as though the third floor is an addition here as well. But the addition may have been made earlier than the alterations to its neighbor, since the tall windows were done in the same Italianate style as the ones below the third floor. The round bay in front was finished off with a mansard roof, showing the influence of the Second Empire style that was popular here before Romanesque became the big fad.

As the storm clouds rolled in, old Pa Pitt was taking a walk in Mount Washington on a couple of blocks of Virginia Avenue. The neighborhood is an interesting phenomenon: it has always been comfortable but never rich (except for Grandview Avenue), so most of the houses and buildings have been kept up, and most of the renovations show the taste of ordinary working-class Pittsburghers rather than professional architects or designers.

We begin with one of the oldest businesses in the neighborhood: the Wm. Slater & Sons funeral home, which fills an odd-shaped lot that gives the building five sides or more, depending on how you count. Slaters have been on this corner since at least 1890. It is very hard to tell the age of the building, because it is really a complex of buildings that grew and evolved over decades, and each part of it has been maintained and altered to fit current needs and tastes. For example, on a 1917 plat map, the back end of the building is marked “Livery,” indicating that W. Slater had a stable there.

This building diagonally opposite from the Slaters has an obtuse angle to deal with. Its Second Empire features are still in good shape above the ground floor, and the storefront has been kept in its old-fashioned configuration of inset entrance between angled display windows.

Here is a house built in the 1880s, also in the Second Empire style, with mansard roof giving it a full third floor. The house has been kept up with various alterations that obscure its original details (the porch, for example, is probably a later addition), but it is still tidy and prosperous-looking.

It is hard to tell what this building was originally, but Father Pitt would guess it was more or less what it is now: a storefront with living quarters upstairs. The front has been altered so much, however, that it would take a more educated guesser than Father Pitt to make an accurate diagnosis.

This apartment building has also been much altered; the windows in front, for example, were probably inset balconies

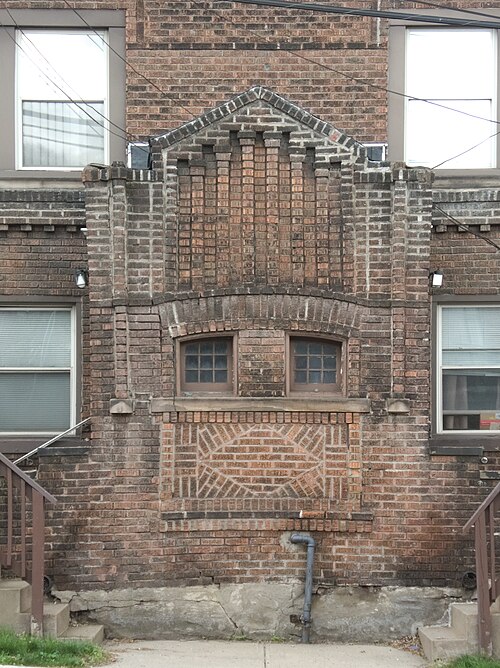

The interesting Art Nouveau detailing of the brickwork reminds us of the work of Charles W. Bier, a prolific architect whose early-twentieth-century work earns him a place among our early modernists, though he turned more conservative after the Great War.

At this point in our walk, the windows of heaven were opened, and the rain was upon the earth, and we retreated to our ark.

Walking down Perrysville Avenue one day not long ago, Father Pitt spotted a distinctive outline through the branches. It was the tower of a Second Empire mansion.

Old Pa Pitt was very excited. Here was a Second Empire mansion he had not known about before. That was very interesting. He started investigating, and found that the discovery was actually much more interesting than that.

Historians of Perry Hilltop are earnestly invited to help us out with the history of this house, which has caught old Pa Pitt’s imagination. The house is in deplorable shape—especially the side you can see through the overgrown shrubbery from Perrysville Avenue, where billows of garbage seem to be spilling out of the building.

But what is fascinating is that, where old Pa Pitt expected a Second Empire mansion, he found something much older. The shallow pitch of the roof and the broad expanse of flat white board underneath the roofline say “Greek Revival” in a loud voice.

This appears to be the side of the house, although Father Pitt has reason for believing that it was originally the front. The large modern Perrysville Plaza apartment building is next to it, but walking around to the back of that building reveals the front of the house—with its distinctive Second Empire tower.

The tower is pure Second Empire, but the roof still says Greek Revival. The house must have been Second Empired, probably in the 1880s. The attic windows in the gable ends were added then: they match the ones in the tower.

The Second Empire remodeling was not the last big change. You may have noticed that there is something a little off about the brick walls. This appears to have been a frame house originally. Old plat maps show it as a frame house through 1910; later maps show it as brick. A brick veneer must have been added at some time around the First World War. The new brick walls swallowed all the window frames and other trim that would have given us more clues about the original date.

There was a house here belonging to the “Boyle Heirs” in 1872, the earliest plat map we have found. An 1882 map shows a carriage drive leading to the plank road that became Perrysville Avenue, with a circle at the end of the house near the road—bolstering old Pa Pitt’s guess that the end was originally the front.

There are few Second Empire mansions remaining in Pittsburgh, and even fewer Greek Revival ones. This house ought to be preserved, but it probably will not be. The neighborhood is neglected enough that it has not even been condemned yet, which means that it will continue to decay until either it becomes an intolerable nuisance or the land becomes valuable enough to build something else on. Father Pitt will label it Critically Endangered.

All we can do, therefore, is document that it exists, and Father Pitt has done the best he can do without trespassing.

Some day some clever inventor will patent a way to match mortar colors in brickwork and make a fortune. (That was sarcasm, by the way: it can be done, but first you have to realize that it ought to be done.) Nevertheless, this building looks much better than it did a few years ago, when the front was covered with aluminum, fake stone, and asphalt shingles. Was it absolutely necessary to brick in all the side windows? Well, probably. Otherwise light might leak in. The original building comes from the 1880s, and the basic outline of it remains Victorian Gothic.

This building also seems to have been put up in the 1880s, or possibly as early as the 1870s. It has been so thoroughly remodeled so often that it would be hard to guess what it looked like originally; Father Pitt’s best guess would be that it had a Second Empire mansard roof and details, replaced in the 1970s by the parody of a Second Empire roof we see today. In the past two decades, the ground floor has been completely redesigned twice; the current incarnation is better than the way it looked twenty years ago.

Here is a Second Empire building that retains much of its original detail, in spite of the complete remodeling of the ground floor (the original design probably let in far too much natural light) and the artificial siding on the dormers.

The corner of Sidney Street and South 19th Street, where we find a Second Empire building with a beautifully kept storefront.

A few weeks ago old Pa Pitt took a wintry walk on North Avenue (which used to be Fayette Street back when it did not run all the way through to North Avenue on the rest of the North Side). He took piles of pictures, and although he published four articles so far from that walk (one, two, three, four), there’s still quite a collection backed up waiting to be published. Thus this very long article, which is a smorgasbord of Victorian domestic architecture with a few other eras thrown in. Above, a pair of Italianate houses. They both preserve the tall windows typical of the high Italianate style; the one on the right still has (or has restored) its two-over-two panes.