You never know what you might find when you go trawling in the depths of the archives. These pictures were taken in September of 2014, but old Pa Pitt never published them. Why not? His memory is vague, but he suspects it was because he was planning to publish them when he worked out the history of the building, and he never did work it out. Finding the pictures by random luck the other day stimulated him to finish the job, and here they are.

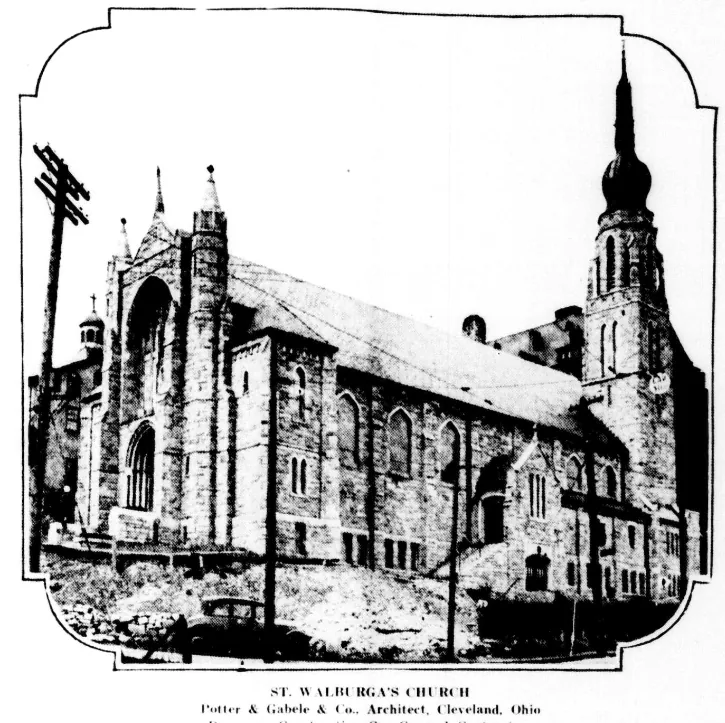

St. Walburga’s was a German parish founded in 1903—the last ethnic German parish founded in the city of Pittsburgh. The cornerstone of this building was laid in April of 1927; the building was dedicated a year later in April of 1928. The architects were the Cleveland firm of Potter & Gabele & Co., and if Father Pitt told you how much time he spent trying to find that information before finally locating it in the Pittsburgh Catholic for April 19, 1928, you would wonder a little about whether he should be regarded as competent to manage his own life.

J. Ellsworth Potter was a successful architect who designed churches in traditional styles until his death in 1958. Henry Charles Gabele was associated with Potter until 1932, but after that seems to have fizzled out as an architect (see a brief notice in this PDF Cleveland Architects Database).

St. Walburga’s parish was suppressed in 1966, a victim of postwar demographic change. Today the building belongs to the Cornerstone Baptist Church, whose congregation obviously treasures it and keeps it in beautiful shape.