This article is a first attempt at a history of the Mercantile Library, and it is doubtless riddled with errors and misapprehensions. It is the product of two afternoons of obsessively trawling the depths of old newspapers, and Father Pitt will correct and improve it as better information comes in.

On June 2, 1845, the Pittsburgh Gazette ran this little item:

☛Thomas H. Perkins of Boston has presented $2500 to the Mercantile Library Association of that city. We wish some of the rich men about Pittsburgh would take it into their head to give a handsome sum toward a Library Association of that kind in this city.

It is possible that a movement was already afoot when the unknowing editor wrote those words, because only two years later we find officers being elected for a Young Men’s Mercantile Library Association and Mechanic’s Institute (Pittsburgh Gazette, July 31, 1847, p. 2). On September 20, 1847, we find an advertisement in the Post that “The Young Men’s Mercantile Library and Mechanic’s Institute is open to subscribers from this date. ☛Hall in Gazzam’s Buildings opposite Philo Hall.”

At this point you may be wondering why the name Carnegie is stuck in your mind as the founder of public libraries in Pittsburgh. The answer is in those little words “open to subscribers.”

In the early and middle 1800s, big cities had circulating libraries open to the public, but most of them were subscription services. You had to pay for the privilege of checking out books. Thus, even though the library was ostensibly aimed at the education of young men, there was a barrier to entry. Andrew Carnegie remembered the charity of Col. Anderson in Manchester, who had a large library and opened it for free to working boys on Saturday afternoons, meaning that even the poorest could educate themselves if they were motivated. There is a reason “FREE TO THE PEOPLE” is engraved over the entrance to the main Carnegie Library in Oakland: that was Carnegie’s great ideal.

Still, a public library was a good thing to have in a growing city, even if you had to pay for a subscription. It was consistently difficult to keep that subscription money coming in, though; reports from the directors usually showed about a quarter of the subscribers in arrears. Nor was there ever a very large number of subscribers; the numbers, as far as old Pa Pitt can determine, never went much above 500. A report in 1852, for example, showed 305 subscribers, including 10 life members.

From the start, “lectures of a popular and scientific character”—one of the primary forms of intellectual entertainment in Victorian times—were an important part of the program at the Mercantile Library. The admission charge was supposed to help pay for the library establishment, but even with a program of popular and talented lecturers, it was hard to fill the seats. In that same 1852 report, the directors took the opportunity to chastise the taste of the public.

The Board of Directors do not like to complain, but it some times happens, when complaint is made, that the proper remedy is provided and a cure effected.

They therefore state—yet with regret and mortification—that in this city, noted for the enterprise and industry of its citizens, lectures got up for their gratification and improvement, the proceeds arising from them, to be applied to an object so praiseworthy as a public library, have not been fully sustained, whilst thousands of dollars are annually taken from their pockets to line those of strolling musicians, and mountebanks of every grade. The fact is bad enough, and we forbear comment on the subject.

Buried in this item, by the way, is a priceless glimpse of the lively Pittsburgh street life of the 1850s.

After the Civil War, there was a general sense of unbounded prosperity in Pittsburgh, and in 1868 the ambitious directors of the Mercantile Library Association undertook to give the Mercantile Library a magnificent new home—the building you see at the head of the article. From a report of the directors published in January of 1869:

“The plans for the building submitted by the architect, (Leopold Eidlitz, of New York) were adopted by the Board of Managers in May last, and Messrs. Barr & Moser of this city, were appointed superintending architects…”

Leopold Eidlitz was one of the most important American architects of the middle 1800s. Among other projects, he had designed P. T. Barnum’s eccentric Orientalist mansion Iranistan (which burned nine years after it was built). Barr & Moser were probably the most important Pittsburgh architects at the time; among their surviving works are the Armstrong County Courthouse in Kittanning and Old Main at Pennsylvania Western University, California.

The building was expected to cost $175,000—a prodigious sum in those days. To put it in perspective, the same report of the directors tells us that “the receipts for the past year, including $201.78 balance in Treasury, January 1st, 1868, were $4,608.21.” However, wealthy investors were persuaded to put up the money, and the building went up. The 1869 report contained a long description of the building as it was expected to be constructed, which you can find at the bottom of this article.

In order to separate the business of the building from the business of the library, a separate company called the Mercantile Library Hall Company was chartered to take charge of the building. The investors who financed it were financing this company on the expectation of getting a good return on their investment. Once those investments had been paid off, the building would become the property of the Library Association.

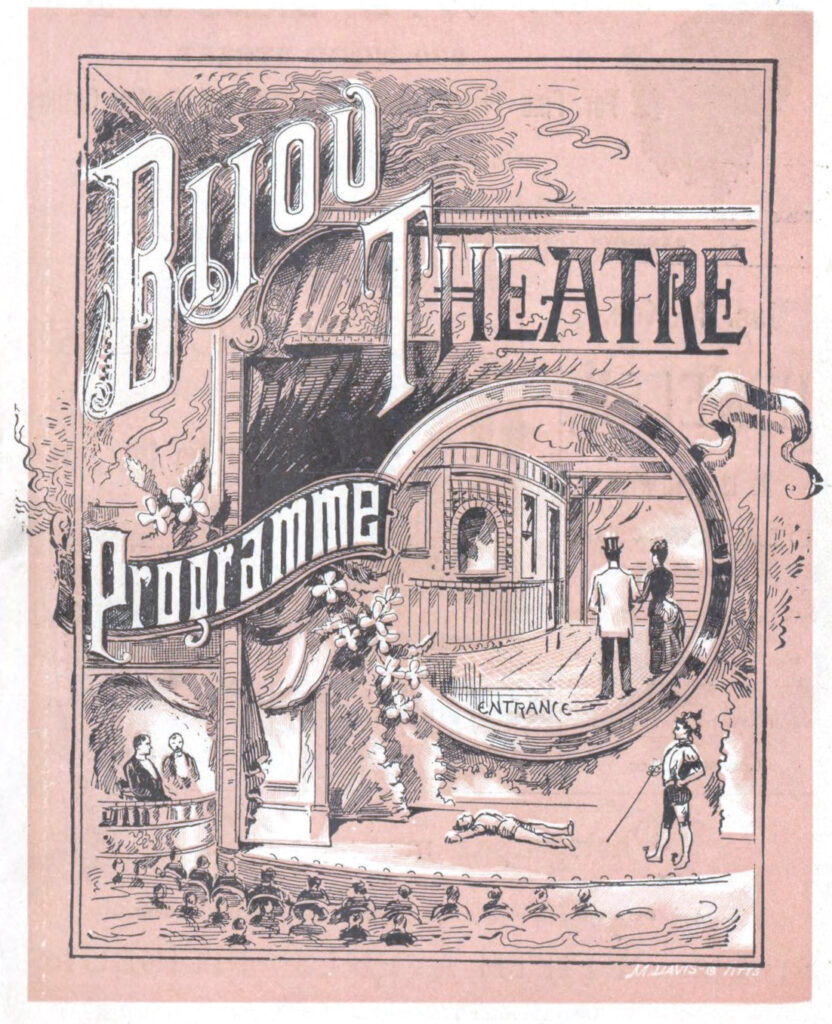

The profit was expected to come from rentals. The library would occupy the second floor; the ground floor would include storefronts and a magnificent auditorium. “It will be constructed upon the plan of a theatre, with a single gallery and will seat comfortably about 1,400 persons.” (For comparison, the Byham Theater today has a seating capacity of 1300.) This auditorium could be rented for a theater when it was not in use as a lecture hall, and an 1883 guide (from which the picture of the hall was taken) describes the building as “Library Hall, frequently called Penn Avenue Theatre.” By the late 1880s the theater was known as the Bijou.

An 1890 article in the Dispatch tells us that the Panic of 1873 was very destructive to the fortunes of the Mercantile Library Hall Company. We forget today that the depression of the 1870s used to be called the Great Depression until we had a greater one. It was a bad time to be trying to pay off an extravagant building. Instead of making a profit, the company accumulated debts, and it could not dig itself out of the hole even when better times came. In 1889 the building just escaped a sheriff’s sale, and again in 1890.

Meanwhile, the theater that rented the auditorium was thriving, and its managers had their eye on the building. “As theater managers they have made a record of conducting the most successful and profitable theater yet known in Pittsburg,” says that 1890 article in the Dispatch. The directors of the library fought long legal battles with the theater managers, accusing them of plotting to force the Library Association into bankruptcy and acquire the building.

And at the same time, Andrew Carnegie was plotting the Mercantile Library’s downfall from another direction, although he had nothing against the institution. Construction of the Carnegie Library for Allegheny began in 1886, while the battles over the Mercantile Library were raging. In 1890, while the Mercantile Library was facing a sheriff’s sale, the city was occupied with the question of what to do with the magnificent gift Carnegie proposed to offer for the construction of a public library for Pittsburgh.

Small wonder that, though the Library Hall Company managed to avoid the auction block at the last minute, the stockholders were receptive to offers. In December of 1890, it was announced that the theater managers had purchased a controlling interest in the company. They had acquired the building.

In theory the Library Hall Company was still obliged to turn the building over to the Pittsburgh Library Association (as it was renamed at some point) when the investors had been repaid. In practice, that was never going to happen. The Association quivered on the brink of dissolution for several years, and in 1899 it moved out of the building. Rescued by the generosity of a rich resident of the up-and-coming borough of Knoxville, the books were moved to the Knoxville Public School, and in May of 1899 a gala opening was held for the new location.

After that Father Pitt has lost track of the library for now. It was still going in 1910, when it was mentioned among the area’s many public libraries as “the Mercantile Library upon the South Hills, rich in Shakespeareana.” But the fact that, on this list, it came after the main Carnegie Library, all the branches, and the Carnegie Free Library of Allegheny shows that the old Mercantile Library had sunk into at best local relevance for the Hilltop neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, the theater in old Library Hall flourished for many more years as the Bijou, and then in a larger building on the same spot as the Lyceum. Most of its patrons probably forgot or never knew that a library had once been there.

Description of the Building

“Local Affairs,” Pittsburgh Post, January 12, 1869, p. 1

The building will occupy a ground space of 120 feet front on Penn street by 160 feet deep along Barker’s alley. Its architectural style is Byzantine, with a Manzard roof. The front will be of dressed stone, the sides and rear of brick, with stone dressings. The town story will be divided into six compartments. That which is nearest to St. Clair street [Sixth Street today] will be occupied for the main entrance and staircase to the Library and auditorium. That on the east side will be arranged for a confectionary and restaurant for ladies and gentlemen, and the four intermediate, will be handsome store rooms extending back the entire depth of the building. At the northwest and north east corners will be additional staircases leading from the auditorium.

On the first floor (or second as we are accustomed to call it [that is, the floor above the ground floor]) in front will be the accommodations for the Library. The Library hall will be one hundred feet by forty, and forty-six feet high, with a gallery surrounding it at seventeen feet above the floor, the gallery to be ten feet wide and to have a handsome cast iron railing. It will be reached by ornamental iron staircases.

At the west end of the hall is a special reading room for ladies, forty by eighteen feet two inches, Including small dressing apartment. Over this room, and accessible from the galleries, is a room of corresponding size for gentlemen.

In the rear of the east end is the Librarians room 54 feet 4 inches by 17 feet 2 inches, which ls entered from the main floor and has also a door opening to the delivery room. Over the Librarian’s room is the Directors’ room of the same size, reached from the gallery. Both of these front on Barker’s alley.

Adjoining the north side of the library, and between the last mentioned rooms and the staircase, is the Book Delivery room, 79 feet by 84 feet four inches, which it is proposed shall be used also as the newspaper reading and for conversation. It will be lighted by skylights, and a part of the floor will be of slate glass, so as to convey additional light to the stores below.

In the rear of these apartments will be the Auditorium, 116 feet by 78, inches, [sic] inclusive of stage and foyer. It will be constructed upon the plan of a theatre, with a single gallery and will seat comfortably about 1,400 persons. The seats and all the arrangements of the hall are proposed to be of the most approved kind.

On the third or upper story, immediately over the auditorium, is a space 118 feet long by 68 feet wide and 17 feet high, which can be divided as may seem best for the uses to which it may be devoted, A portion of it will be required for a small hall for the ordinary meetings of the association, and it has been suggested that the north half of this space, or a part of it, would be admirably adapted to the requirements of the Academy of Design.

In the front part of the building, over the library, is a room 116 feet long by 40 feet wide, and 16½ feet high, which at some future time will be needed in connection with the library, but which until then may be devoted to other uses. It would make a very good gallery for the exhibition of pictures. By introducing the light from above (a modification easily made,) it would be particularly well suited for that purpose. The objection to a location on the upper story, which would be of force in other cities, would be more than counterbalanced in our dark atmosphere by the advantage of being free from any other obstruction to the light.

Comments