The Hall of Sculpture in the Carnegie (as seen by the ultra-wide auxiliary camera on old Pa Pitt’s phone, so don’t expect too much if you enlarge the picture), designed in imitation of the interior of the Parthenon.

Comments

The Hall of Sculpture in the Carnegie (as seen by the ultra-wide auxiliary camera on old Pa Pitt’s phone, so don’t expect too much if you enlarge the picture), designed in imitation of the interior of the Parthenon.

The vestibule at the original entrance to the Carnegie Institute building, seldom used now because visitors come in through the modernist Scaife Galleries addition. This picture was taken hand-held in dim light with the ultra-wide auxiliary camera on old Pa Pitt’s phone, so please forgive its obvious flaws.

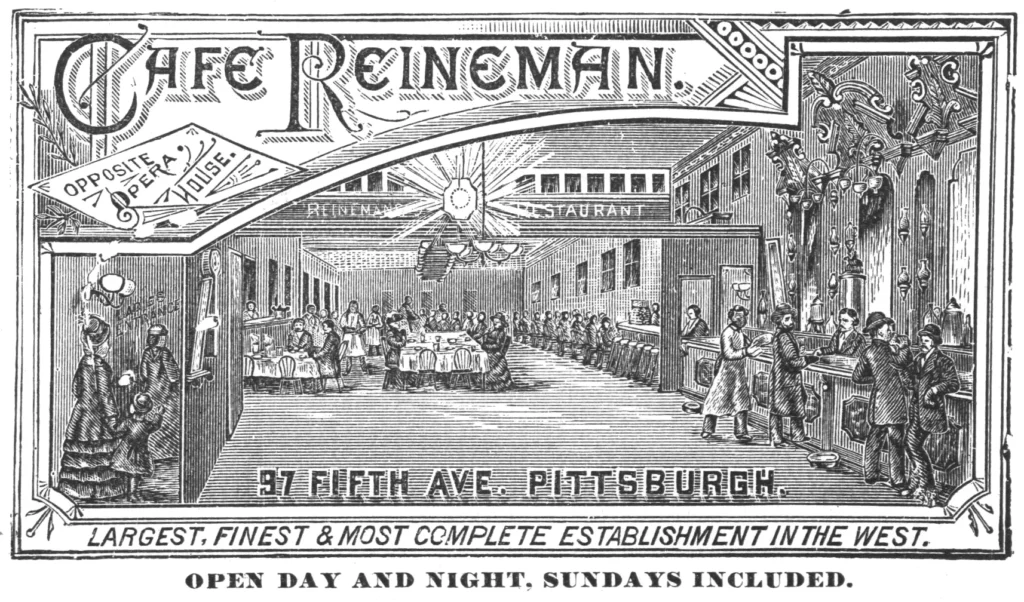

A look at the interior of the Cafe Reineman on Fifth Avenue shows us what was expected of any establishment claiming to be the best restaurant in Pittsburgh, and indeed west of the Allegheny Mountains. It is brightly lit by gas—the artist has made the illumination by large chandeliers a prominent feature. It has tables for couples and families arrayed in efficient rows to accommodate many guests and leave room for the waiters to navigate. It has an ornate bar with immense mirrors and proper facilities for expectoration on the floor. For single gentlemen diners, there are stools along the wall. For unaccompanied ladies, there is a Ladies’ Entrance as far from the bar as practically possible, allowing them to pass into the eating part of the establishment without enduring rude remarks from the expectorating drunks—who appear to be starting a fight even in the drawing, as if a bar without a fight would be an unacceptable omission in the most complete establishment in the West. And, of course, the location is important: just across from one of the main theaters, the Opera House, whose last incarnation became the Warner. (Note that address numbers on Fifth Avenue have changed: this would be at about 343 Fifth Avenue now.)

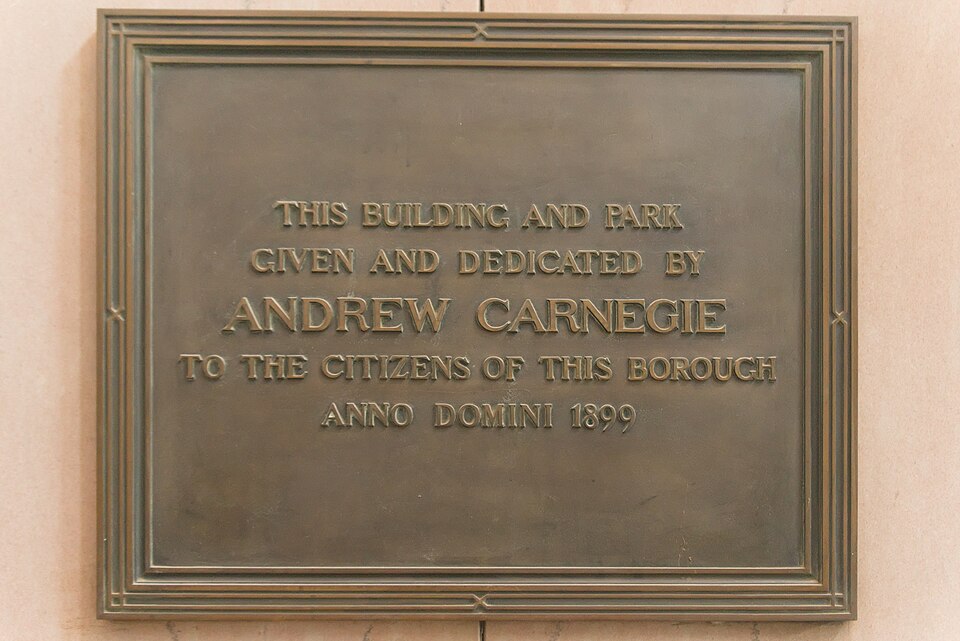

Officially the Andrew Carnegie Free Library, or the Carnegie Free Library by the inscription over the door, but the name “Carnegie Carnegie” is obvious and irresistible and adopted for the library’s Web site.

When the two Chartiers Valley boroughs of Mansfield and Chartiers merged in 1894, they decided to name the new town Carnegie after what was probably the most familiar name in the Pittsburgh area. In return, Andrew Carnegie gave them the jaw-dropping sum of $200,000 for this magnificent building (designed by Struthers & Hannah), plus money for books and—unusually for Carnegie—an endowment. His usual agreement with towns that took a library from him was that the town must undertake the upkeep, thus making the citizens ultimately responsible for their library; but in a few steel towns (where we suppose he felt more personally responsible) he endowed the library with enough of a fund to keep it going indefinitely.

Like Carnegie’s other steel-town libraries, this one was not just a library. It also had a music hall, a gymnasium, and a lecture hall.

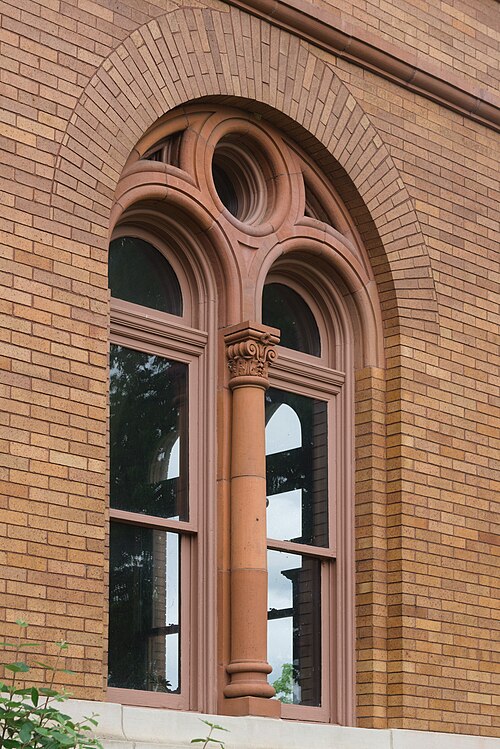

Note the terra-cotta lyre over this window on the music-hall front of the building. Today the music hall is still delighting audiences, and the library sticks to its mission of being a welcoming place to go read a book.

Columns of the Composite order, the most elaborate of the five classical orders, send the message that this is not just a library but a palace for the people.

The lobby lets us know that we have entered a building of unusual richness. Marble panels cover the walls, and mosaic tile decorates the floor.

The Greek-key pattern in the tile is repeated in the risers in the stairs.

On the second floor of the building is an extraordinarily well-preserved post of the Grand Army of the Republic, and Father Pitt will try to return soon for some pictures of the room.

The interior of the library itself mimics the experience of being a rich man with a big library—like old Col. Anderson, whose library was Carnegie’s model. You walked in, sat in front of a big fireplace, and had servants bring you books, and for an hour or two you were just as wealthy as Carnegie himself.

Open stacks have eliminated the servants, but the fireplace is still there, with a familiar face over the mantel.

In days of gaslights and low-wattage early electric bulbs, natural light from outside was still important for a reading room. Fortunately no one ever had the money to block up these windows.

All the windows are surrounded with elaborate terra-cotta decorations.

The Hall of Sculpture was designed as a model of the interior of the Parthenon. It used to be crowded with plaster casts of antique sculptures; most of the casts have been moved to the Hall of Architecture, leaving the Hall of Sculpture mostly empty except when special exhibits are mounted there.

The building was designed by Longfellow, Alden & Harlow; the murals were painted by John White Alexander.

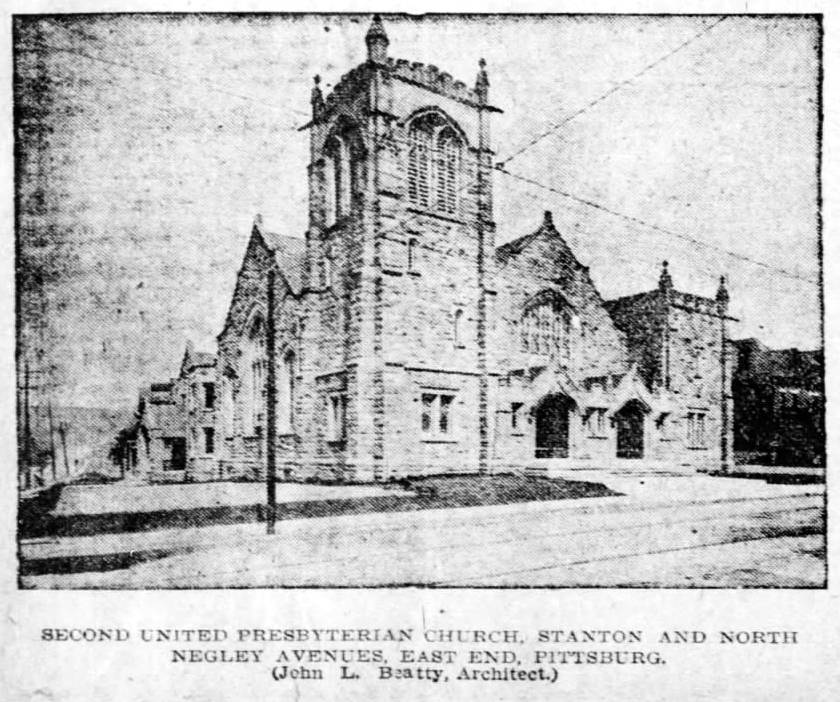

We have seen pictures of the outside of this church before—here, for example, is a picture from May of 2021:

The other day the current inhabitants, the Union Project, were kind enough to turn old Pa Pitt loose in the sanctuary to take as many pictures as he wanted.

The architect was John L. Beatty, who designed the building in about 1900. A newspaper picture from 1905 (taken from microfilm, so the quality is poor) shows the exterior looking more or less the way it does now.

After a disastrous fire, much was rebuilt in 1915, again under Beatty’s supervision.1 Another fire in 1933 would necessitate rebuilding part of the tower.

The church was built for the Second United Presbyterian congregation, which had moved out to the eastern suburbs from its former location downtown at Sixth Avenue and Cherry Way (now William Penn Place)—exactly one block from the First United Presbyterian Church, which moved to Oakland at about the same time. Later it became the East End Baptist Church, and then was renamed the Union Baptist Church. When that congregation folded, the church was bought by a Mennonite group that founded the Union Project. It is now a community center for pottery, because “everyone should have access to clay.” The sanctuary—which has been preserved mostly unaltered, except for the removal of pews and other furnishings—is available for large events.

The sanctuary is roughly square, which is typical of many non-liturgical Protestant churches in Pittsburgh at the turn of the twentieth century. Above, looking up at the center of the ceiling.

The stained glass was restored as part of a remarkable community effort in which people in the neighborhood learned the art of stained-glass restoration themselves. It would have cost more than a million dollars to have the work done professionally, but volunteers learned priceless skills, and the glass is beautiful.

The vestibule includes some of the original furniture from the church, and some smaller stained-glass windows.

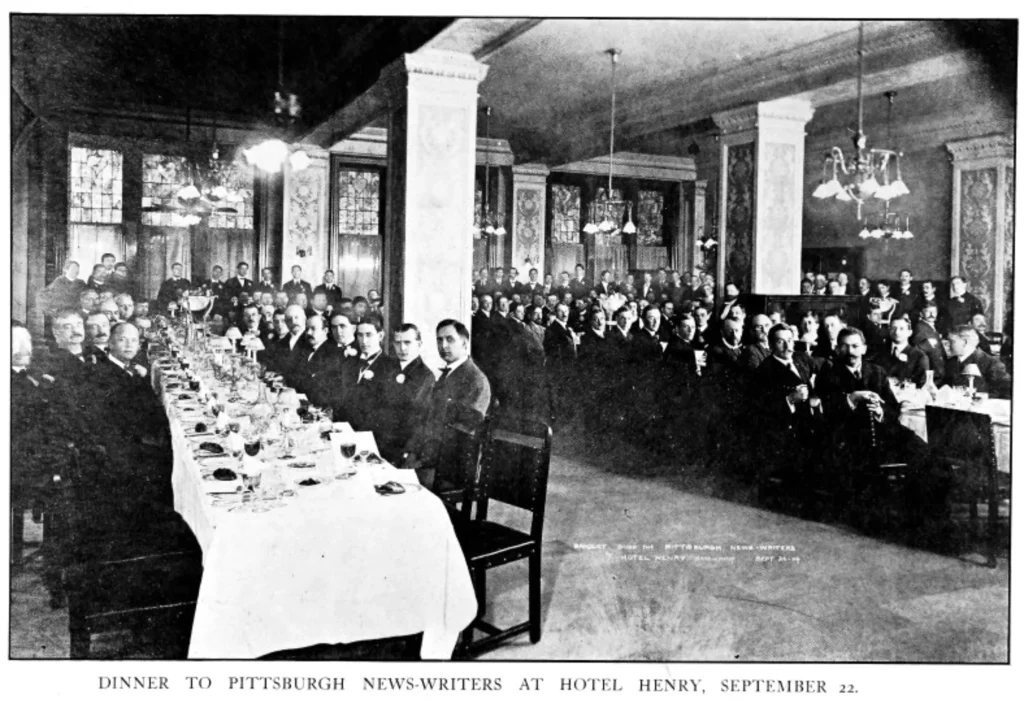

The Hotel Henry was on Fifth Avenue; it was replaced in 1951 by the Mellon Bank Building (525 Fifth Avenue). Here we see a huge banquet for the newspapermen of Pittsburgh in 1904, which incidentally gives us a look at the posh appointments of the banquet hall.

One of the chief attractions of the main Carnegie Library is the Reference Department, a huge room with a vaulted ceiling where you can walk in and ask a librarian for help on any topic, and then have librarians scurrying back into the stacks looking for obscure volumes to aid you in your research. Think of it this way: at no cost to you, simply by walking into this room, you can have the experience of being a supervillain with an army of minions.

The coffered ceiling was originally full of skylights—a maintenance headache rendered less necessary by bright modern lighting.

Mural decorations—lost for years behind paint, found accidentally in 1995, and carefully restored—pay tribute to famous printers of the Renaissance. A report by Marilyn Holt (PDF) describes the murals in detail. Above, the mark of Aldus Manutius, perhaps the greatest of them all.

Reginaldus Chalderius (or Regnault Chaudière, as he would have been called at home), French printer at the sign of L’homme sauvage.

Balthasar Moretus, Antwerp printer of the middle 1600s.

Thielman Kerver, Parisian printer at the sign of the Unicorn.

Noli altum sapere—“Do not be proud”—say the Estiennes, Parisian printers.

Jean de la Caille reminds us that prudence beats force—Vincit prudentia vires.

Simon Vostre, early French printer.

Many of the details in the decorations are picked out in gold leaf.

From The Brickbuilder in 1913, two views showing how interior spaces in the Allegheny County Soldiers’ Memorial were illuminated.

An interesting note on the auditorium: In 1960, Syria Mosque across the street was the usual venue for Pittsburgh Symphony performances. But when the Symphony made some high-tech ultra-high-fidelity recordings for Everest that year, conductor William Steinberg insisted on using the auditorium in Soldiers and Sailors Hall instead. He thought the acoustics were much better. Those Everest recordings are still regarded by connoisseurs as some of the most real-sounding symphonic recordings ever made.