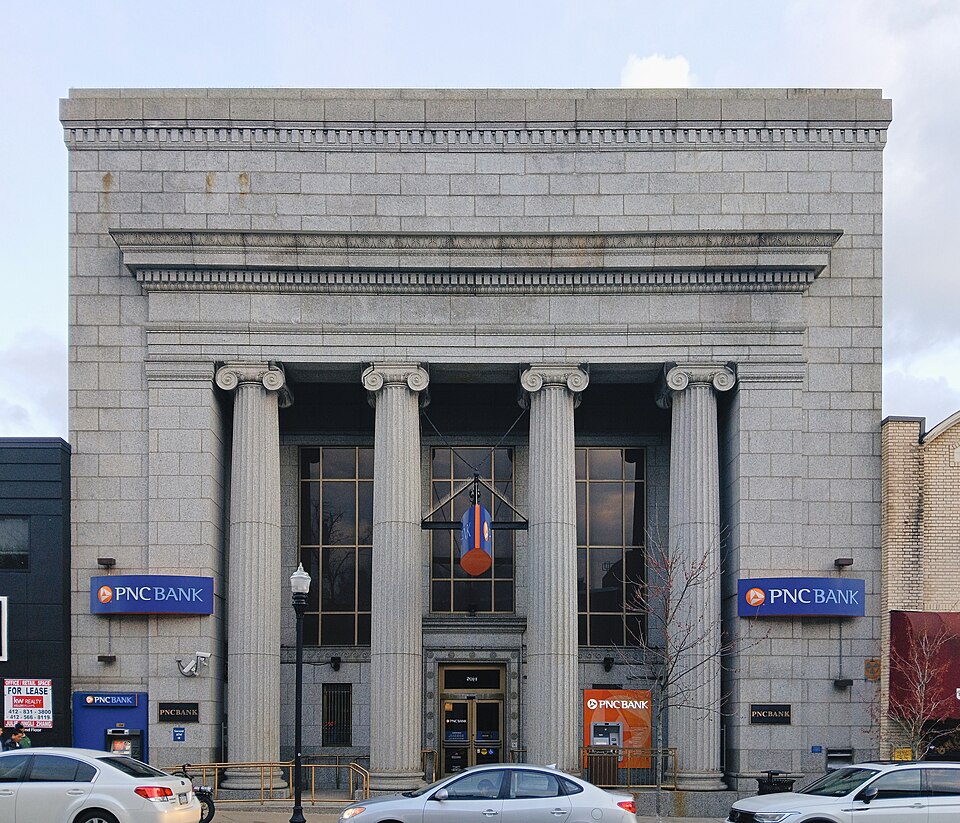

George S. Orth, who lived in Bridgeville, designed this building,1 which was put up in two stages, beginning in 1903 or 1904, for the Bridgeville Trust Company. If you look very carefully, you can see the seam in the middle of the long side along Station Street, marking the line between the original square building on the corner and the later addition behind it. At some time in the middle twentieth century, the ground floor was entirely redesigned to look more like a modern bank, so that only on the second floor is Orth’s work visible today. The building was still a bank (a branch of PNC) until just a few years ago.

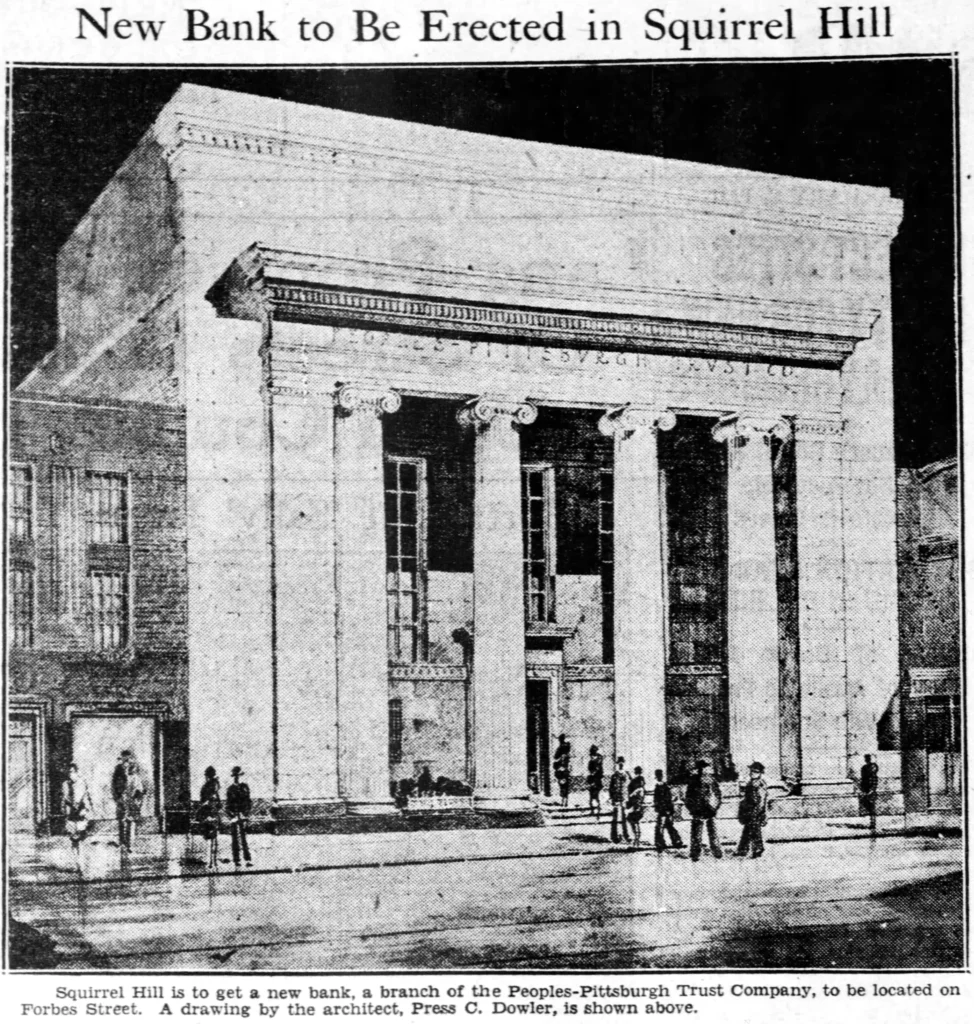

Across the street, the First National Bank of Bridgeville was going up at the same time. James E. Allison was the architect of this one.2 Soon—probably while this building was still going up—he would take his brother David on as a partner in the firm of Allison & Allison. In 1910 they moved to Los Angeles, and they flourished there as architects of some of the most notable buildings in the city.

- Philadelphia Real Estate Record & Builder’s Guide, September 30, 1903, p. 341 (641; pages are misnumbered): “Architects G. S. Orth & Bros., Stevenson Building, have completed revised plans for the erection of a two-story brick bank and office building to be erected for the Bridgeville Trust Company, of Bridgeville, Pa. The cost will be about $20,000.” ↩︎

- Record & Guide, November 18, 1903, p. 763. “At Bridgeville, Allegheny county, the First National Bank will erect a building two stories high, of stone and brick, all modern conveniences. The plans have been prepared by J. E. Allison, Westinghouse Building, Pittsburg, Pa.” The building ended up with three floors, but Hopkins maps show the First National Bank at this location. ↩︎