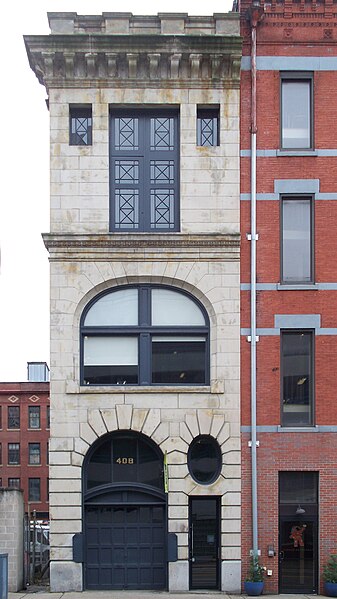

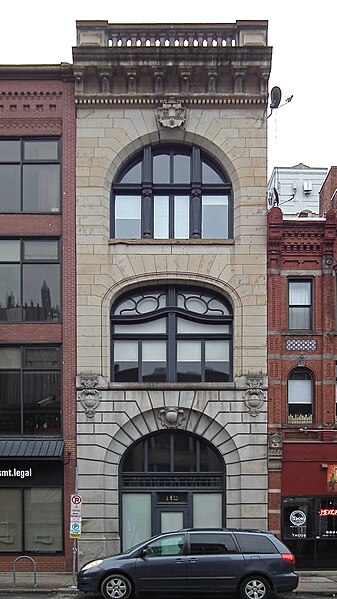

The Pittsburgh Meter Company building was put up at some time between 1910 and 1923, right beside the Brushton railroad yard, with a siding to serve the factory. It has been beautifully restored as the Sarah B. Campbell Enterprise Center, and it is filled with artists’ studios. One of the wonders of the big city is that we can find many buildings this size filled with artists’ studios; it reminds us why the word “civilization” means life in cities.

In the days when this building went up, it was usual for companies like this to make their main factory buildings as attractive as possible. The building itself was one of the chief advertisements for the firm, and an engraving of the building—sometimes exaggerated if the building was not as impressive as the company would like—appeared in advertisements and brochures as a guarantee that this was a solid and respectable business. Thus the entrance and the corners of this building are decorated with up-to-the-minute Art Nouveau geometric patterns in terra cotta.